That’s another British prime minister the Rolling Stones have outlasted.

When the band first plugged in under that name at London’s Marquee Club on July 12, 1962, Harold Macmillan was in Number 10 dealing with the “little local difficulty” of sacking a third of his cabinet. Then came Alec Douglas-Home, Harold Wilson, Ted Heath, Wilson again, Jim Callaghan, Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, David Cameron, Theresa May and now the soon-to-depart Boris Johnson. Thirteen administrations, an even dozen US presidents and six popes. And through it all the Stones themselves have just kept rolling along. Not bad for a band of misfits that everyone, including them, thought would last a year or two at most.

When longtime Stones scribes like me come to consider the matter of the group’s most famous, or notorious, acts during their first sixty years together, they’re somewhat spoilt for choice. The hack’s eye might turn to some of the drug-related adventures of the 1960s, or to today’s superbly efficient mobile corporation, which even now continues to pack the sports stadiums of Europe. My own candidate for inclusion on the Stones’ greatest-hits list is more modest. It took place on the snowy night of February 12, 1977, at a thatched cottage in an otherwise silent village in the English countryside.

Here’s the backstory: exactly ten years prior to this date, the Stones’ Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were relaxing with some friends in that same bucolic setting of West Wittering, Sussex, which Richards has long made his English home. Around eight at night, a party of nineteen policemen knocked at Keith’s door. They had a warrant to search the premises, and eventually removed a number of heroin phials (“for diabetes,” he explained) owned by the band’s friend Robert Fraser, as well as four Benzedrine tablets in a jacket belonging to Jagger. Before taking their leave, the police warned Richards that, if the confiscated items were found to contravene the Dangerous Drugs Act, he, as the householder, would also be charged.

The raid on Keith’s place turned out to be one of those events whose actual success — four pep pills between the two Stones — was the least important factor in its public reception. From now on, the band would be as polarizing in their own way as Bonnie and Clyde, or, more prosaically, England’s recently jailed Great Train Robbers: either heinous thugs or plucky scapegoats. In Britain in 1967, you either loved the Stones or you hated them. What few people did was to ignore them. Everyone had heard the story that Jagger’s partner Marianne Faithfull had been found by the police that night in an unusual combination with her boyfriend and a Mars Bar. It was totally untrue, although Marianne did calmly greet the law while clad only in a fur rug, a detail that produced a nearly physical tremor when later related in court.

When the time came, the judge in the case told the jury that they were to put completely out of their minds any prejudice they might have about the Stones’ looks, clothes, habits, lifestyle or music. They were to disregard the testimony they had heard over the course of the previous two days describing the interior of Richards’s house as a scene of smoke-filled decadence out of some banned Arabian erotica, to ignore everything they had read and heard about the semi-nude girl who had opened the door, and not to let her rum behavior in any way influence their verdict. The jury found both Jagger and Richards guilty. They were given three and twelve months respectively, but in the end spent only a day inside and got off on appeal. Robert Fraser had a less high-powered lawyer and served his full six-month sentence.

In February 1977, I was nineteen, obsessed with the Stones and not yet in full control of my senses. As a result, I convinced myself that it was a good idea to visit the scene of the great West Wittering raid of ten years earlier, and somehow persuaded two of my Cambridge college friends to accompany me. It was the middle of the English winter, and as I knew Keith also owned a beachfront pad in Jamaica, I fully expected to find a locked front gate awaiting us.

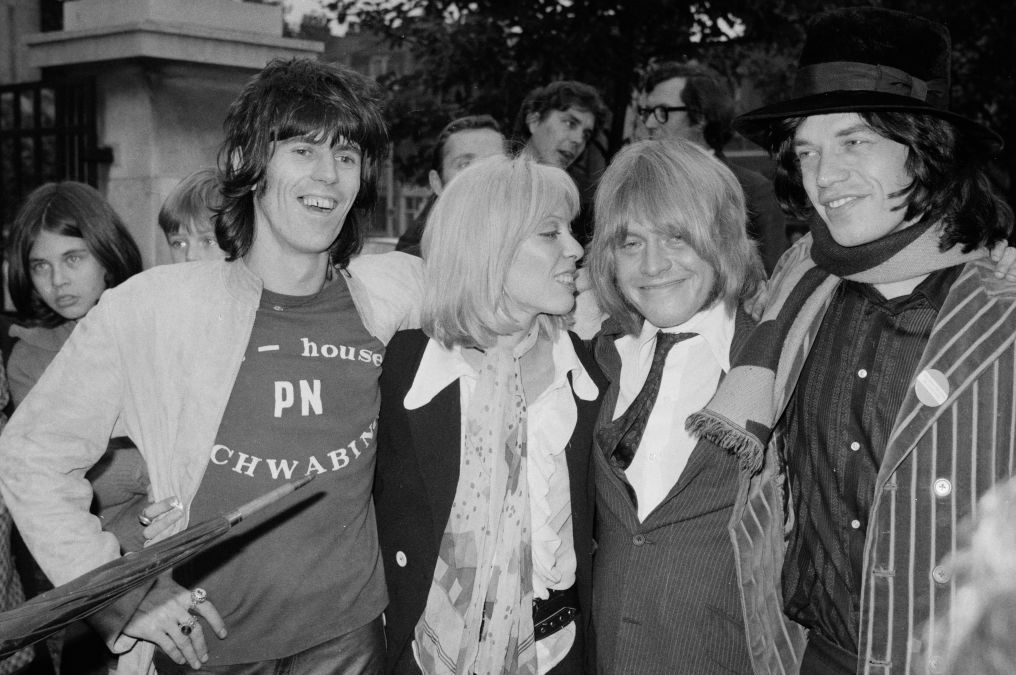

We were in for a shock. As we turned down the narrow lane leading to the house, we saw unmistakable signs of Stones-like activity on the premises, with expensive American cars parked in the driveway and thumpingly loud reggae music blasting out of the windows, both somehow incongruous here in West Wittering. Taking a deep breath, we rang the front doorbell. There was the sound of someone laboriously opening a series of locks and bolts on the other side, and then suddenly Keith Richards himself stood before us. It was about twenty-five degrees that night, but Keith was dressed for the tropics, barefoot, and looked impressively wrecked. He was also remarkably friendly under the circumstances. “Hi,” he said, as though merely greeting some expected guests.

I later wrote a book about the Stones — and among my minor discoveries was that in February 1977, the band had been negotiating a new record deal, and that in the end it was thought easier for the suits to come to Keith and company for signature, rather than vice-versa. That would explain why, to our amazement, Mick Jagger and Charlie Watts were also on the premises when we walked in, the former tinkling a grand piano in the corner, the latter standing at the fireplace dressed in a three-piece tweed suit. Keith himself was hospitable, although he winced when we reminded him of the particular significance of the date. “The fuzz are still a pain in the bum,” he told us. “Well, not really a pain, they’re more of a habit.” Keith reflected further, and added sadly, “An expensive habit.”

Apart from the three Stones, there was quite a lot else to catch the eye in Keith’s front room, where a pair of razor-pointed sabers hung somewhat intimidatingly over the roaring log fire. A large, nearly albino dog — named Ratbag, we learned — was sprawled on a Persian rug, periodically emitting gastric noises and dubious smells in counterpoint to the music. A kaftaned blonde woman lay supine next to it, smiling beatifically but not making any other sign of life. Most of the room’s furniture seemed to be made of antlers, with tribal masks displayed on the wall and a lot of Moroccan-looking drapes and cushions. Taken as a whole, the place could have doubled as the clubhouse of a voodoo cult or the set of a rather heavy-handed Stones biopic. There was a thick film of haze everywhere.

Mick Jagger was charming, with a smile like that of a model in a toothpaste advertisement. Keith told him why we were there, and he laughed some more. “Happy Anniversary! Mick,” he scrawled unbidden on a piece of paper, which I still own today. Charlie Watts was affable, but seemed a bit bemused by the whole thing. “You drove here from Cambridge?” he kept saying. “Cambridge University?” It obviously struck him as highly eccentric behavior on our part — and of course he was right.

There were more handshakes and autographs — though, alas, in those pre-cellphone days, no photos — before we left, and the three of us drove back through the snow in a state of mingled euphoria and disbelief at our blind good luck. My last memory of the night was seeing Keith standing silhouetted in the doorway, a tiny figure with hair piled up as high as a guardsman’s fur cap. Only about a week later, he was pulled over by the police on his arrival in Toronto after allegedly bringing a suitcase full of drugs into Canada. The charges carried a possible sentence of seven years to life, and if proven would almost certainly have spelled the end of the Stones as we know them. But that’s another story.

Christopher Sandford’s biography of the Rolling Stones, Sixty (Simon and Schuster), is available now.