Louise Perry is on a mission: “It wasn’t enough just to point out the problems with our new sexual culture,” she declares at the start of her punchy first book The Case Against the Sexual Revolution. So she offers advice as well to the young women she believes have been “utterly failed by liberal feminism.”

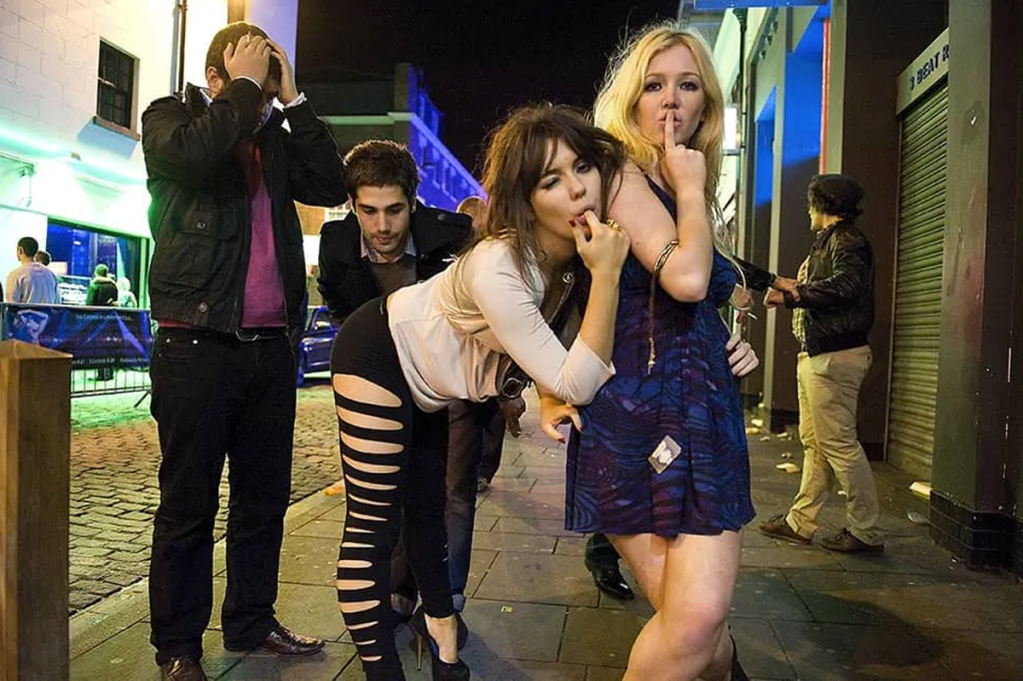

That’s because contemporary sexual mores have exposed them to risks, the most serious of which are linked to some men’s propensity for violence. Women, Perry argues, have in recent decades been conditioned to repress their desire for attachment. They have learned instead to behave in ways more typical of men, with their greater (on average) appetite for casual sex or “sociosexuality.”

Perry, who says that working for a rape crisis service changed her attitudes, points to the dangers of sadomasochistic sex, as shown by the rise of the “rough sex” defense, whereby the growing number of women (and smaller number of men) killed by their partners are claimed in court to have consented to the violence which led to their deaths.

But Perry believes the problem goes deeper. She attacks the normalization of extreme pornography, hook-up culture and the apps which promote it, and the ethically weak concept of consent whereby a person’s agreement to any given activity is regarded as the last word.

Missionaries preaching sexual restraint are liable to be mocked — and Perry has been compared to Mary Whitehouse. But Christian morality is not the motivation for the sexual counter-revolution she proposes. She does not want a return to the way things were before birth control and abortion were legalized, when single mothers were stigmatized and their babies taken away from them. Instead of this punitive double standard, she argues for a new sexual settlement which allows for differences between males and females, and a version of feminism that supports this. Above all, she objects to what she calls “sexual disenchantment,” whereby physical intimacy between people is treated as little more than a hobby. And she argues that poor and vulnerable women pay the heaviest price in the current conditions, since money, education and other forms of privilege are, as ever, to some extent protective.

Some feminists, of course, realized long ago that sexual and women’s liberation are not the same thing. Sheila MacLeod wrote in 1988 of her generation’s discovery that “the world of male fantasy fulfilled did nothing to add to the sum of their own happiness.” What Perry’s “post-liberal feminism” does is to bring this unfashionable insight up to date. In doing so, she walks a tricky line. The UK, her home country, has no equivalent to the US Christian right. But connections between homophobia and conservatism (sexual, religious, political) did not disappear with Section 28, the 1988 British law banning councils from the “promotion of homosexuality.”

Forty years on, Perry seeks to turn the tables. Restrictions on human sexual behavior are not necessarily right wing, she argues. In fact it is those who advocate for freedom above all other values who are the “sexual Thatcherites.” Their scorn for norms and taboos, and laissez-faire attitude to sex businesses (including pornography and BDSM, with its many shop-bought accessories) has turned them into proselytizers for a deregulated sexual marketplace.

In a sense I am the wrong reader for this book. At fifty, and married, I do not need Perry’s guidance on how to find love and security — or why to avoid selling naked pictures of myself to pay my rent. But as someone who grew up in liberal north London in the 1980s and drank in many of the same ideas as Perry has, I found this book riveting. Like her, I am dismayed by the uncritical embrace of a simplistic credo of anti-repression. I, too, have noticed belatedly the extent to which feminists closed themselves off from evolutionary understandings of human behavior, with even the monumental achievements of scientists like Sarah Blaffer Hrdy mostly ignored in favor of ideas from the humanities and critical theory.

Perry pushes in the opposite direction. One of her book’s most provocative sections makes use of Craig Palmer and Randy Thornhill’s argument in A Natural History of Rape, that there is an evolutionary explanation — which is not the same thing as a justification — for male sexual violence. And she tears into the widely revered Angela Carter for her literary celebration of the “Sadeian woman.” To dignify the Marquis de Sade in this way, Perry argues, is to sanitize the actions of the Peter Sutcliffe of his day.

I don’t agree with Perry that young women should avoid getting drunk in mixed company or have sex with a man only if they think “he would make a good father.” She overdoes it when she says that independence is “nothing more than a blip” between stages of life when we depend on others. Her final command to “listen to your mother” assumes that all mothers have sensible things to say. Some women should do the opposite.

But her challenge to commodified, dangerous sex, and the liberal rights advocates who promote it, is timely. More truth and less wishful thinking is a wise message. Anyone who cares about intimacy should be willing to think about it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.