Like someone who has bought a first computer, then reads the manual from front to back but never actually gets around to switching the thing on, Robert A. Heinlein appears in his late fifties to have come across a how-to book about sex. Thereafter an instant expert, he wrote novel after novel brimming with it, much of it laughably theoretical and, well, wrong. Famously, to those who managed to get through an interminable book called The Number of the Beast (1980), he describes a kiss in the voice of a young woman: ‘Our teeth grated, and my nipples went spung!’ Nor were these the only breasts and nipples under discussion. The book is full of lubricious references to them, and other women’s parts, invariably objectified. About genuine sexual feeling or activities, Heinlein is coy.

Not unrelated to this, he was a rampant sexist, the sort of man who praises the superiority of women while inadvertently revealing that deep down he is full of prejudices and controlling instincts. Worse, he was a racist in an identical way. Examples abound, most of them devastatingly analyzed in Farah Mendlesohn’s The Pleasant Profession of Robert A. Heinlein.

Older male writers of the 20th century do have the half-excuse that ‘it was different in those days’, but Heinlein was an active writer well into the 1980s, when social awareness and change had been on the agenda since about 1970, and sensitivity to these matters was out in the world. There is no excuse, except the disagreeable one that he probably thought he was right and that it felt urgent to say so.

Mendlesohn describes how Heinlein, who when younger had made a well-earned name for himself as an author of serious and innovative speculative fiction, became a rotten writer in the second half of his career. He always told stories well, but his style was execrable. From Starship Troopers (1959) onwards, his books had an endlessly hectoring, lecturing tone, almost always phrased in long and unconvincing conversations full of paternalistic advice, sexual remarks, libertarian dogma and folksy slang. Reading one of his later novels produced the weird effect of meaningless receptivity: you could get through 20 pages at a gallop, but at the end you couldn’t remember anything that had been said, by whom or for what reason. The next 20 pages would be the same (but seemed longer).

Heinlein was a sixth-generation German-American. The family was proud of the fact that every Heinlein had fought in an American war (from the War of Independence onwards), but Robert was the first who did not. Although he served in the US Navy in the 1930s, and was honorably discharged, by the time World War Two started he was medically unfit for more than a civilian role. You can’t help feeling that this disappointment must have colored some of his purpose when writing.

The stories and novels from the pre-war part of his career were notable for the firm sense of competence and reliability. They were, like his later work, told well. His style was terse, rather like that of a literate drill sergeant. Unlike the other science fiction current at the time, Heinlein’s speculative stories were not only set in plausible futures, but the people who moved in those worlds were strong, believable and effective.

At the end of the war he began a series of juvenile novels, aimed unerringly at young readers but told in the same didactic voice. These novels had a profound effect on their American readers. There is still today a generation of middle- aged and elderly American science fiction writers for whom Heinlein is in a position of seminal influence, similar to Hemingway in other literary circles. Heinlein’s influence on modern American science fiction is not universal, but still detectable.

In the 1950s he wrote some of his best adult novels, notably Double Star (1956), in which an actor is recruited to impersonate an important politician, and The Door into Summer (1957) — a time-travel novel for cat lovers everywhere.

On politics, Heinlein wrong-footed his critics. Broadly speaking he was always a libertarian, but when he was young he described himself as a left-leaning liberal, and when older became not exactly extreme right-wing but everything but. He was full of seeming contradictions. As a libertarian he of course loathed big governments, but also as a radical thinker believed in world government, the biggest one of all. He supported the family unit but never had children. He was outspoken on the need for an American nuclear build-up, and was a vocal supporter of civilian guns — he coined the phrase ‘an armed society is a polite society’ — but several of the later novels questioned the actual and moral deterrent effectiveness of guns.

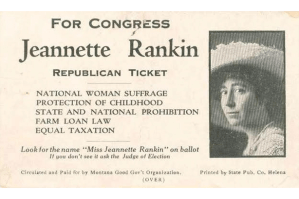

Mendlesohn’s book bespeaks long and detailed work, but the result is difficult to read and follow. After a brief biography the book is separated into thematic discussions: Heinlein and the civic society, the ordering of self, an alleged cinematic technique, etc. These vague subjects are thoroughly and intelligently discussed but they wander from one story to another, presupposing that the reader will instantly recall in detail every one that is mentioned. The text needed a thorough and intelligent editor too. The book, which is almost as long as Heinlein’s Time Enough for Love, cries out for a proper index. For now it will act as an instruction manual on Heinlein, but its academic reliance on secondary texts will deter many readers who might otherwise be interested.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.