Of all the things in the world of entertainment that might get me excited, “a new Michael Mann project” tops the list. A film writer and director, Mann not only is a talented storyteller, but has mined the criminal underworld for his subject matter, from his debut feature in 1981, Thief. Since then, he’s rarely veered from criminal elements in his subject matter (Last of the Mohicans and Ali being the two notable exceptions). He is the great auteur of the crime genre; in other words, he makes arthouse films for dads.

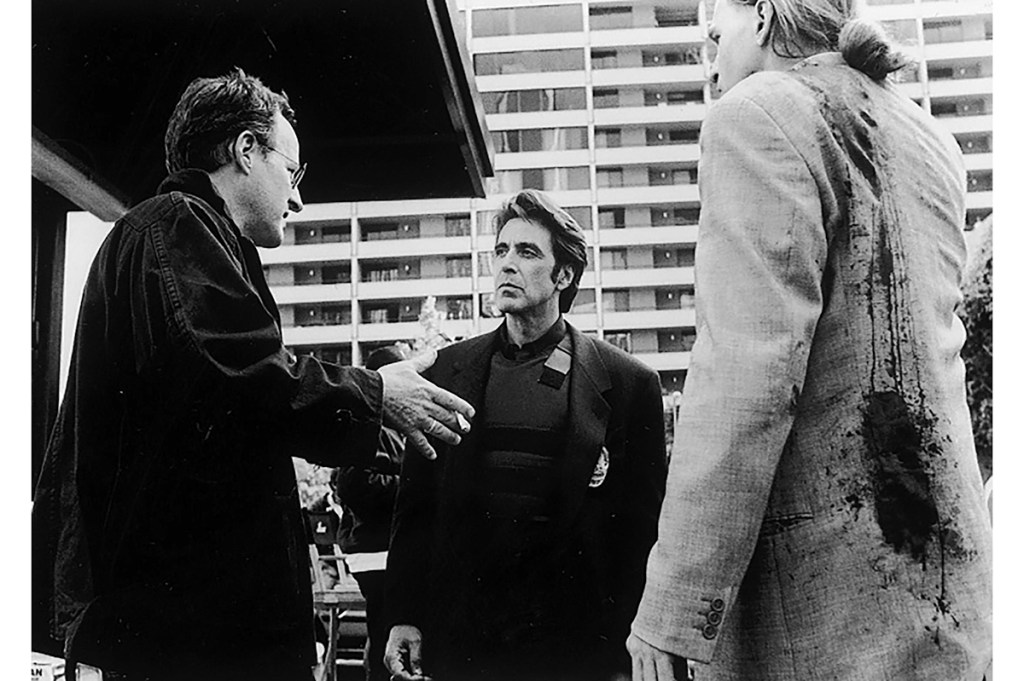

In 1995 Mann released what many consider to be the greatest crime film ever made. Heat told the story of Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) and his crew, a group of master thieves who live to take down scores, in a cat-and-mouse game with a relentless cop named Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino) and his team of detectives. Boasting an all-star cast, including De Niro and Pacino on screen together for the very first time, it was more than a crime film. It redefined a genre and set a standard that every genre picture made since aspires to. The story, the dialogue (or lack thereof), the cinematography: everything came together to create a perfect film that you can’t take your eyes from.

Heat was based largely on real life. There was a real-world McCauley, a former Alcatraz inmate who took down huge scores in Chicago. He was eventually tracked down by Chuck Adamson, the inspiration for the Pacino character. Adamson went on to become a major Hollywood consultant and producer, creating a series produced by Mann and starring Dennis Farina, himself a former cop who worked for Adamson in Chicago.

Realism permeates Mann’s world, and the world he created in Heat was rich enough for the writer-director to decide that he needed to expand the universe further, this time with a novel. Imaginatively titled Heat 2 and co-written with veteran thriller writer Meg Gardiner, it dives deeper into the rich criminal underworld and complicated lives of his thieves and cops.

Covering a twelve-year period both before and after the events of the film, the story skips around from McCauley and his crew’s early exploits in Chicago in 1988 to the transformation of crew member Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer in the movie) into an international black-market dealer years after their botched score in the film.

The novel begins with McCauley and co. plotting a heist at a mob-connected bank full of safe deposit boxes, the contents of which are unlikely to be reported stolen by their owners. Meanwhile, his eventual nemesis Hanna is a young cop in the Chicago Police Department with tours in Vietnam and DePaul Law School under his belt. He’s rising fast in the department because of his dogged pursuit of targets and his willingness to cut corners. The reader understands that he and McCauley have more in common than might be comfortable for either to admit.

Fueled by cocaine — appropriately replaced with the legal substitute, Adderall, as his drug of choice later in the book — and prostitutes, Hanna prowls the streets looking for a low-level crew of sadistic criminals committing home-invasion burglaries, rapes and murders in Chicago’s Lincoln Park and Gold Coast. Mann paints a picture of Chicago in the late 1980s that skillfully transforms the city into a character of its own, just as Los Angeles has a starring role in Heat.

As the novel progresses, McCauley moves onto an even bigger job on the Mexican border, setting off a string of events that all lead back to Hanna and the last survivor of McCauley’s crew — Chris Shiherlis. He is in Paraguay in a low-level security job in Ciudad del Este, a sort of South American Casablanca full of smugglers, cartels, syndicates, spies and other unsavory characters.

The story is quintessential Mann. We are introduced to a world reminiscent of the criminal empires that he created in his films Miami Vice, Collateral and Blackhat, with an emerging international dark economy fueled by narco-states, rogue oil kingdoms, criminal syndicates and brilliant gentleman thieves doing deals with the highest bidders. Mix in mercenaries and a corrupt defense contractor and you get a sense of what you’re in for with this novel.

Unusually for screenwriter, Mann manages to keep literary interest fresh. Heat 2 retains a cinematic quality in its structural leaps from 1988 to 1996 to 2000 and back again, keeping the reader guessing where it is heading before full circle in a way you don’t see coming. And, perhaps cunningly, it leaves the door open for yet another sequel.

The filmmaker can definitely write, though this may well be helped by his choice of co-author, who has fourteen novels under her belt. The prose has a staccato quality, with short declarative and direct sentences. Published under Mann’s own imprint at HarperCollins, Heat 2 looks unlikely to be his last foray into novel writing. If you’re a fan of the crime genre, you can only hope we get more from him and his crew soon. But Michael, don’t leave the films, OK?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2022 World edition.