The scene is becoming so familiar that it’s starting to feel like a ritual. Young people, wearing solemn faces bordering on scowls and graphic T-shirts emblazoned with slogans, part the crowd and hurl cake on the “Mona Lisa” in Paris, chanting incantations and invectives about the impending apocalypse. They then glue themselves to the wall.

Something like this has played out in several European cathedrals of high culture, from the National Gallery in London to the Museum Barberini in Potsdam. Tomato soup was splashed on a Van Gogh. Mashed potatoes, splattered on a Monet. A bald head was glued to a Vermeer.

Whatever did the Renaissance painters and Impressionists do to inspire such defacement? The point, it appears, is to raise awareness of our climate crisis. As one of the pink-haired activists inveighed after gluing herself to the wall, “what is worth more, art or life? Is it worth more than food? Worth more than justice? Are you more concerned about the protection of the painting or the protection of our planet and people?”

This vandalism has got me thinking about my home country, Singapore, and the case of Michael Fay, an American who was flogged for vandalism in the mid-1990s.

After pleading guilty to the theft of road signs and spray-painting cars, Fay, then an eighteen-year old student, was sentenced to a jail term and six strokes of the cane by a Singaporean court. The story made headlines worldwide. It even triggered a diplomatic row after President Bill Clinton weighed in on the case, calling the punishment “extreme” and “a mistake” before directly appealing to the Singapore government for clemency.

Fay’s sentence was eventually commuted to four strokes of the cane, a punishment that I, as a kid growing up in Singapore, had regarded to be cruel and unusual at the time. Now, I find myself wondering: might a flogging be just the punishment for today’s eco-nihilists?

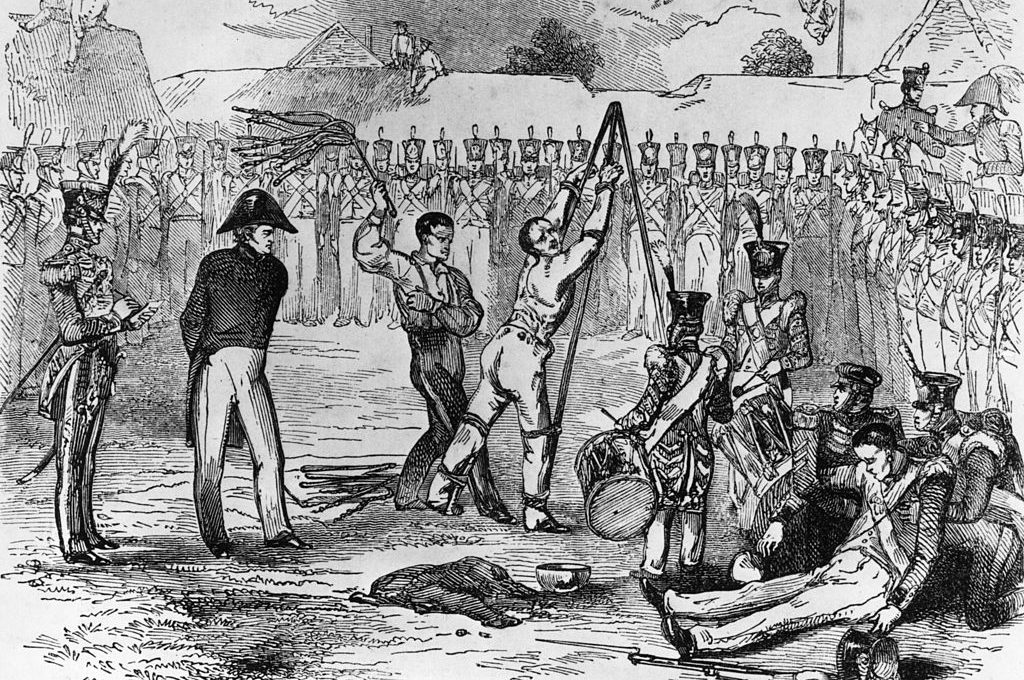

The caning meted out in Singaporean jails isn’t just another version of spanking. The prisoner is bent over while strapped down on an A-frame trestle, his buttocks exposed. A strip of rattan, dipped in water to slightly stiffen it, is wielded at such a high velocity that it often flays the flesh. When Michael Fay went on CNN’s Larry King Live after the ordeal, he described the excruciating pain and said that the wounds bled as much as a “bloody nose.”

This all seemed punitive and unnecessary to me, in retaliation for the “mere” act of vandalism. Fast forward just over twenty-five years, and I’m beginning to wonder if my younger self got it wrong.

“Unlike some other societies which may tolerate acts of vandalism, Singapore has its own standards of social order as reflected in our laws,” the Singapore government said in a statement responding to complaints by American officials at the time of l’affaire Fay. “It is because of our tough laws against anti-social crimes that we are able to keep Singapore orderly and relatively crime-free.”

I no longer use the term “mere” as an adjective to describe the act of vandalism. It is a subversive act, often done by those who feel powerless. Their aim is to leave an indelible mark on the symbols we value. That indelibility is what distinguishes vandalism from pure mischief. It imposes real costs on society.

Setting aside the merit of their hysterical arguments (the German activists who lobbed mashed potatoes on the Monet screamed that “we won’t be able to feed our families by 2050 because of climate change”), the antics will ultimately lead to closures and increase security and insurance costs for art museums everywhere, directly impacting the public’s access to treasured works. Some in the media have emphasized that all the recently targeted works of art were enshrined in panels of glass for protection, but according to museum staff, those panels weren’t designed to keep liquids out.

Besides, no amount of glass can attenuate the very message that the activists are trying to send: we despise you, the public, and we despise our rich cultural history, which is but a weight to be thrown off our backs. Art has been the epitome of self-actualization since the dawn of our species. It is fundamentally a primal expression of the human spirit and emerges from cultural flourishing. Destroying it is one of the most profoundly anti-human acts, aligned with the evil ideologies of history’s worst actors from the Nazis to the Taliban.

Permitting the defacement of objects of historical and emotional heft that belong to society at large is a shortcut to civilizational demise and only further encourages further brazen acts in the name of activism. Which brings us back to what we should do with vandals hellbent on unilaterally re-writing history and snuffing out the creativity of the human soul. Corporal punishment, in Lee Kuan Yew’s words, “is not painless. It does what it is supposed to do, to remind the wrongdoer that he should never do it again.”

Flogging may extract a sliver of flesh, but it is nothing compared to the physical, emotional and spiritual damage that leads us inexorably down the path of civilizational suicide. It’s a painful reminder that no one has the right to do his bidding onto property that he does not own. In some ways, it’s also far more humane and less life-disrupting than prolonged incarceration.

What the West needs now is corporal punishment as a form of broken-windows policing. The results speak for itself — not only is Singapore free from the blight of graffiti, any citizen or visitor with a penchant for artistic transgressions is strongly disincentivized to even begin contemplating such an act.

There must be a cost to such anti-social actions. We need to make the activist who shouted “are you more concerned about the protection of the painting or the protection of our planet and people?” to consider whether she is more concerned about buttock pain or the high that comes from the self-righteousness of her moral crusade. These climate activists are no more than spoilt children whose tactics are infantilizing the apocalypse and marching us toward civilizational decline. Given the stakes, we should bear in mind what they say about sparing the rod.