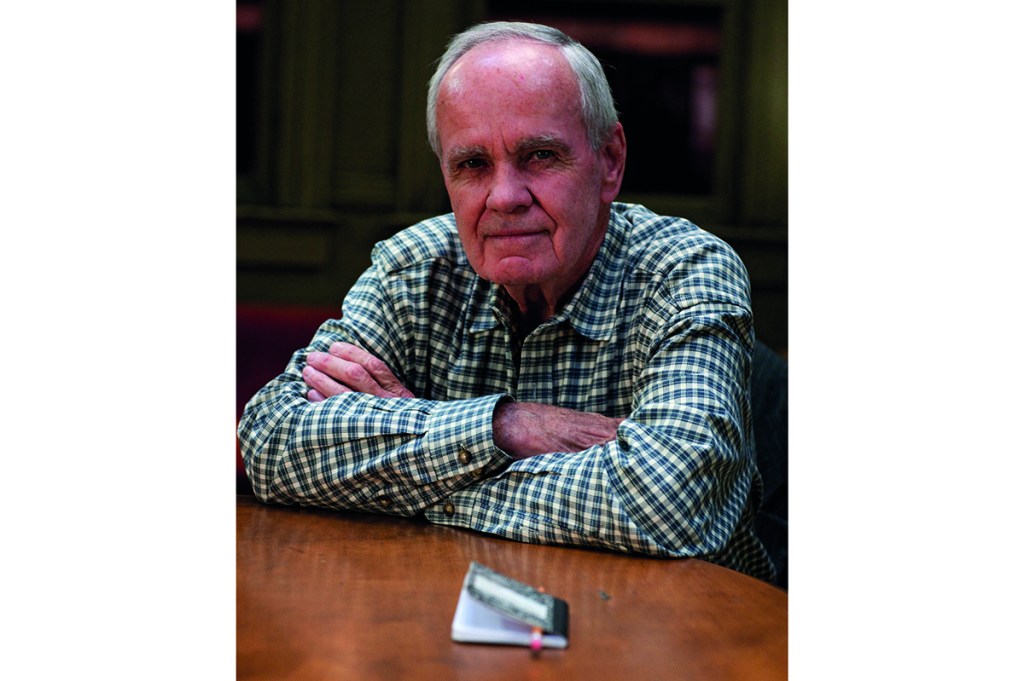

Cormac McCarthy of all living American novelists has realized most fully the potential grandeur of his métier by revealing the spiritual condition of our time in the old epic language. In this sense, he is the most serious American novelist of the post-war era.

McCarthy’s work is magnificently oblivious to modern industrial and technological society and to the post-urban and suburban culture of consumerism, triviality and superficiality that are its fruits: the penalty a decadent civilization pays for its self-alienation from nature, humanity and metaphysical reality, and its embrace of an artificial world in which what is real and human withers and dries up, and art becomes well-nigh impossible. McCarthy’s solution for this basic artistic obstacle has been to set all of his novels with the exception of The Road — a post-apocalyptic story that occurs at some future unspecified date — either in the historical past, or in regional backwaters where modernity has barely penetrated, or both.

McCarthy was born in Rhode Island in 1933 but grew up in Tennessee, where he lived before he moved in early middle age to Texas. The South was thus his formative social milieu, and Faulkner his principal literary influence. For both men the past was dimensionally larger — broader, deeper, more spacious — than the narrow, cramped and shallow present. This is because it lived substantially in its own past; not at the intellectual level necessarily, or even the conscious one, but in the sense that because the radical historical discontinuities of the 20th century had not yet occurred, people were still imaginatively connected to the world as it was before their own arrival in it.

A sense for connections is the basis of all storytelling, and the character of a story determines the language in which it is told. Storytellers with a keen awareness of history and an intuitive sympathy for it are naturally inclined toward an epic sensibility, an appreciation of the portentous and a heightened rhetorical style suited to these things. It is not, of course, the modern style. Once upon a time, that was Hemingway’s. Though Ernest Hemingway was Faulkner’s exact contemporary, their prose (like everything else about their work) is diametrically opposed. In his own estimation Faulkner’s most serious literary competitor, Hemingway once referred to his rival’s later books as being ‘all sauce’.

Had he lived to read the novels of Cormac McCarthy, Papa might have said the same of some of them. Shelby Foote called the English language the real hero of All the Pretty Horses, the first volume in the Border Trilogy. No doubt he meant it as a compliment, which to a certain extent it is. Nevertheless, language does bear some of McCarthy’s novels away with it as violence carries the Kingdom of God, but with less satisfactory results. In this respect they are comparable to Wagner’s Ring of the Niebelungs: what is there is magnificent, but what isn’t there in some instances is overwhelming. Wagner — the Wagner of the Ring, at least — denied that he wrote operas at all; his compositions were ‘music dramas’, he insisted. While McCarthy has never objected to being described as a novelist, one can make a plausible argument for his fictions being something more (or less) than novels, at least as the genre is commonly understood.

They are for the most part strictly linear stories, save for the more modernistic books in which dislocations in time are frequent (Faulkner again). In general McCarthy allows language to do far more of the work, and bear a great deal more of the structural weight, that more prosaic novels leave to the narrative line and the characters to handle. Across page after page in Blood Meridian the author seems compelled to record and name precisely every topographical feature, every species of tree, every type of composite rock the bounty hunters ride past. The tendency is already apparent in The Orchard Keeper (1965), set in rural east Tennessee in the 1930s. Here the descriptive prose, while exquisitely poetic, fails to compensate for faults common to a first novel. In quantitative terms, there is simply too much of it, and overwriting is a serious qualitative problem. Most of this is related to McCarthy’s obsessive quest for photographic and phonographic exactness and verisimilitude, and to the scientific scrupulosity he shares with Judge Holden in Blood Meridian, who catalogs as much of the natural world as he can cram into his notebooks as a means of controlling it.

Nevertheless, McCarthy’s chief weakness as a novelist lies with his characters, always convincing in the detailed minutiae of their appearance, their clothes and their speech, but usually at too steep a price. ‘Ordinary’ people typically have little of real importance or interest to say to each other, but a character in a novel is supposed to be there for good reason — namely, that he is more than an ordinary person, someone who when he speaks has something of more than ordinary interest to say, expressed in a more than ordinarily interesting way. McCarthy’s mainly rural, uneducated people speak exactly as the vast run of ordinary American rustics speak and have spoken for a hundred years and more. The result is that his characters all sound alike as they converse in basic, almost monosyllabic sentences or sentence fragments punctuated by monotonously repetitive four-letter words, profanity and blasphemy.

Fitzgerald jotted in his notebooks that ‘Character is action’, which is true, and a thing no novelist should ever forget. The problem is that ‘action’ in a novel by Cormac McCarthy is nearly always an act of violence, though it may be a brave and even heroic one of the kind that John Grady Cole in All the Pretty Horses and Billy and Boyd Parham in The Crossing perform. Both novels, like their sequel Cities of the Plain, are compelling stories about characters who, though faultlessly true to type, are hardly complex, developed and individuated ones. McCarthy’s great artistic error in the Border Trilogy is his decision to bring the boys together in the final volume — at which point the reader discovers that they are actually one and the same person.

Violence in its most cruel, brutal, sanguinary and explicit (almost pornographic) forms has always been inseparable from McCarthy’s artistic imagination; it is a primary component of his metaphysical vision, most fully and comprehensively expressed in Blood Meridian: Or, The Evening Redness in the West. Set in the late 1840s and early 1850s and based on the author’s extensive research in the gubernatorial archives of the northern Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora, Blood Meridian is the story of a brigade of violent American misfits hired by the governor of Chihuahua as headhunters to slaughter as many borderland Indians — Comanche and Apache, principally — as they can manage and bring their scalps to the gubernatorial palace to exchange for bounty. The party is headed up by Judge Holden, who makes his appearance in the book’s first few pages when he publicly identifies an itinerant preacher as an outlaw guilty of fornication with an 11-year-old girl and bestiality with a goat — charges that he knows to be utterly false and that he naturally expects will result in the man’s lynching by the angry crowd.

[special_offer]

‘This is him,’ the preacher protests to the crowd. ‘The devil.’ As indeed he proves to be. Judge Holden is the judge of this world and the roaring lion of the Old Testament, searching for people to devour. He is also a highly educated and even brilliant man, a naturalist and a classicist, besides being a man of the law. And he is the man who sportively dandles a captured Apache boy on his knee before calmly lifting his scalp. The judge believes, as he states in his Iago-like credo at the end of the book, that, ‘War is the ultimate game because war is at last a forcing of the unity of existence. War is god.’ Otherwise stated, Evil is a god — one that can only be opposed, though futilely, by the kind of courage John Grady Cole and the Parhams possess.

McCarthy has been faulted for the apparent relish with which he describes the cruelest actions: the casual shooting of the dancing bear in Blood Meridian, for instance. At other moments in his stories, casual suffering is merely poignant, like that of the small bird impaled alive and fluttering upon a cactus spine in Pretty Horses. Yet in his relentless insistence upon cruelty and violence, Cormac McCarthy is perhaps making a subtle aesthetic — even a moral — point. After Blood Meridian, his third novel, Child of God, is easily his most horrific. Lester Ballard is a young psychopath who, following his release from prison on a false rape charge, goes on to murder seven people, mostly young girls on whom he performs necrophiliac acts before conveying their corpses to a limestone cave that becomes their mausoleum after he has wrapped them in muslin ‘like enormous hams’. ‘The bodies were covered with adipocere, a pale gray cheesy mold common to corpses in damp places, and scallops of light fungus grew along them as they do on logs rotting in the forest. The chamber was filled with a sour smell, a faint reek of ammonia.’

However shocking it may sound, Child of God is not only among McCarthy’s best novels, it is one of his most poetically concise and beautiful ones as well. I do not think it farfetched to imagine that McCarthy means to suggest the ability of art to conquer insanity and evil by raising them to a higher level, or power. If that is not indeed his intent, the sole plausible alternative is that McCarthy is a nihilist, which I do not believe. Nihilists are without hope. Yet, ‘People without hope,’ Flannery O’Connor thought, ‘do not write novels.’ Meanwhile, Cormac McCarthy has to his credit several of the finest novels published in his 87 years, roughly coincident with the long twilight of American letters.