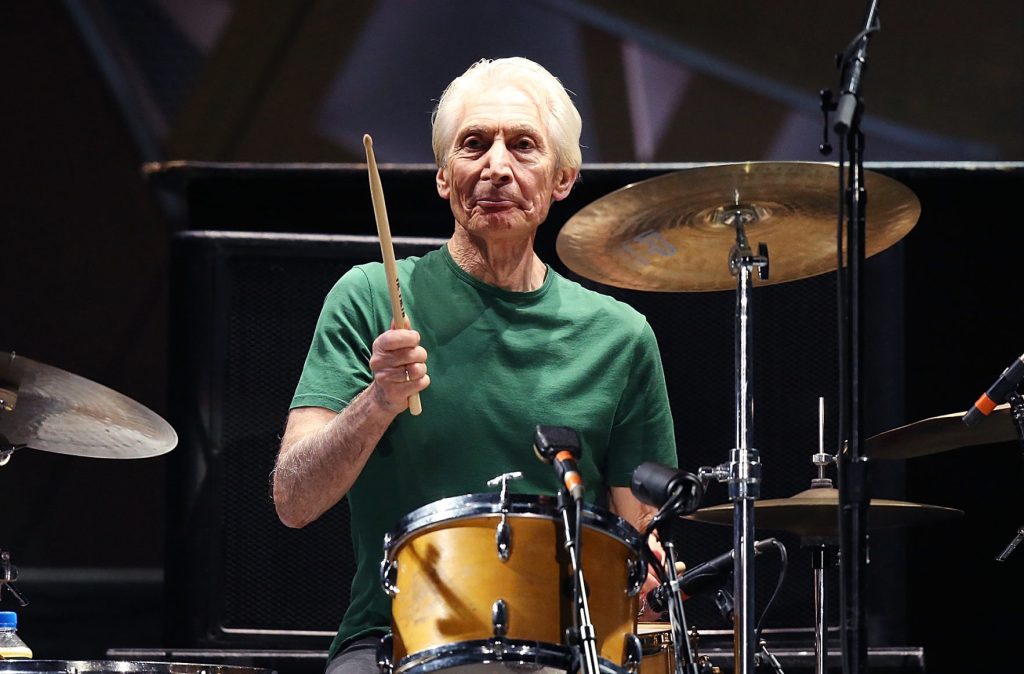

There can be few terms in the English language more debased than ‘rock star’. Nowadays, it seems, the press makes a fetish of every halfway plausible such chancer to appear over the horizon, regardless of whether their art will endure, or their generally slim recorded oeuvre instead be among the detritus one eventually takes to the nearest Goodwill store. But the Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts, who died today aged 80, truly merits a place in the pop pantheon. He wasn’t just an original among the standard tub-thumpers of his profession. He was unique. Back in 1963 the Stones’s first manager, Eric Easton, fastened on the essential thing about Watts, which was that he was ‘totally unpretentious’ and ‘perfect at his job.’ Those same two qualities would remain intact for the next 58 years.

It was a curious path that took the impeccably polite, suave young drummer into a group that were to hear themselves described as ‘morons’ by a High Court judge, and to read newspaper accounts citing their UGLY LOOKS! UGLY SPEECH! UGLY MANNERS! among other unattractive characteristics. Watts, born on June 2, 1941, grew up in and around Islington, north London, at a time when the area was still a byword for urban decay rather than the spiritual home of Britain’s left-wing intelligentsia. His father, also called Charles, was a truck driver, and his mother, Lilian, had been a factory cleaner. ‘He’s always been a good boy,’ Mrs. Watts informed the press in 1967, the year of the Stones’ Their Satanic Majesties Request. ‘Never had any police knocking on the door or anything like that. And he’s always been terribly kind to old people. He was always a tidy dresser. That’s why I get nonplussed when he’s called ugly and dirty. When he’s home you can’t get him out of the bathroom.’

Twenty years later, Watts’s father remained equally perplexed by his son’s public image, especially because Charlie (who never learned to drive) still came up on the tube every Friday night he possibly could, ‘with a lovely fresh cake for me and his Mum.’

Watts himself was later to remark, ‘Part of my problem was that I was never a teenager. I’d be off in the corner talking about Kierkegaard. I always took myself too seriously, and thought Buddy Holly was a great joke.’ It’s true that there was something a bit melancholic about the London lad with the long, Buster Keaton face who only ever wanted to read about cowboys or play the drums. He acquired his first kit at Christmas 1955, after at least a year of practicing nonstop on his mother’s pots and pans. At 18, Watts had only one ambition, which was to somehow find himself at Birdland in New York, wearing a hipster suit and sitting in behind the likes of Stan Getz or Miles Davis. Instead, he drifted in to a smoke-filled suburban London blues club one evening, to be confronted by the embryonic Rolling Stones. They courted him for about two years before he agreed to join, and even then he contained his excitement. The Stones’ roadie and sometime piano player Ian Stewart remembered that he’d simply driven up to the Watts’s front door one night in his van. ‘I said to Charlie, “Look, you’re in the band. That’s it.” And Charlie said, “Yeah, all right, then, but I don’t know what my mum’s gonna say”.’

Amid all the subsequent stories about Mars Bars, drug busts and Margaret Trudeau, Charlie remained the calm eye of the storm. He bought the former Archbishop of Canterbury’s home, raised sheepdogs and collected American Civil War memorabilia. He was the politest man in rock music. Once, in Detroit, a record executive named Mo Schulman invited the drummer up for a drink in his hotel suite, which was awash in champagne, caviar and an impressive variety of recreational drugs. When Schulman was then urgently called away on business, he affably told his guest to help himself from the display. ‘Anything you want,’ he stressed. Charlie took a bottle of beer, leaving both a five-dollar bill and a polite thank-you note on the counter. A few years later the Stones were yukking it up one night in the pinball room of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Mansion with its underwater bar and hot and cold running Bunnies. Charlie took one look at the Satyricon-like scene, rolled his eyes, said, ‘Uh-oh, this is star situation’, and retired alone with a good book.

Watts was also the steadying influence of a band that often seemed to be on the brink of a messy, Beatlesque breakup. For large parts of the 1980s, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were united only in their mutual affection for the dapper, self-effacing man doing the locomotion behind them on stage. Richards called Watts ‘the secret essence of the whole thing’, and ‘the perfect drummer for the material.’ Watts’s light touch and crisp, jazzy sensibility distinguished some of the band’s most iconic songs. Sitting impassively at his minimalist kit, he lit the fuse to ‘Satisfaction’, ‘Honky Tonk Women’, ‘Brown Sugar’ and many others. Variety once wrote of him on stage, ‘He looks like the mild-mannered banker who no one in the heist movie realizes is the guy actually blowing up the vault.’

In 2014, Watts became the first rock star to celebrate a golden wedding anniversary. He married his childhood sweetheart Shirley Shepherd when they were both in their early twenties, and the couple remained together to the end. In later years the Wattses lived on a sprawling farm in the west of England, where she raised Arabian horses and he sometimes liked to sit, in motoring cap and goggles, behind the wheel of his stationary 1937 Lagonda Rapide. When compelled to go on tour with the Stones, Watts typically assumed the air of bemused detachment that was as much a part of the whole spectacle as Mick’s rooster-on-acid gyrations or Keith’s laconic riffing. For years, Charlie enlivened the experience of clocking on and off for rehearsals by the expedient of hanging an old-fashioned shop’s ‘Open’ or ‘Closed’ sign in front of his kit. Drummers, like goalkeepers, are a bit different.

The Stones’s final public appearance with Watts was a filmed segment for the first we’re-all-in-this-together COVID broadcast in April 2020. Charlie played along on a spirited version of ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want’, drumsticks in hand, using a trio of musical storage cases and a nearby couch for percussion. It was an effortless, funny and musically deft performance, and absolutely right for the occasion. Only the drummer in the world’s greatest rock band, it seemed, might not wish to keep a set of drums at home. Somehow that summed up the man.