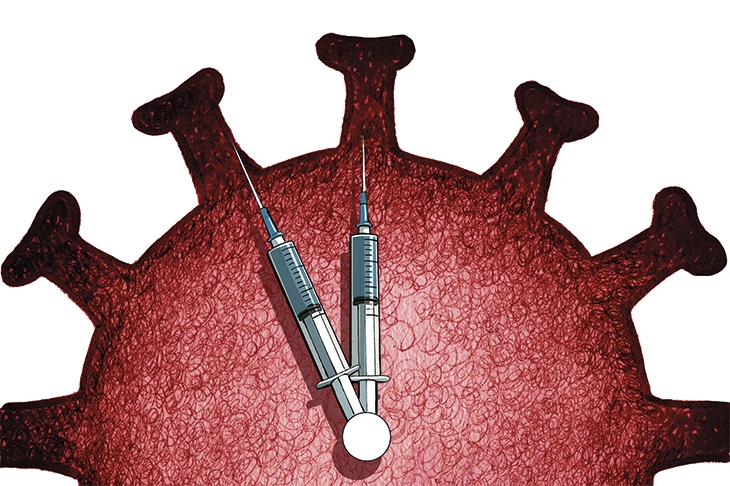

The vaccine programs launched this year appear to offer a Happy Ending to the Horrible Story of the COVID-19 Pandemic. But I am cautious. Not because I am ‘antivax’, but because lasting ‘ever afters’ are never written in the language of emotional manipulation and coercive control.

Herd immunity, when enough people have either recovered from COVID or been vaccinated, will end the pandemic. The pressure to get there has given us a vaccination drive with an unprecedentedly strong behavioral psychology and emergency response approach.

A panoply of persuasions has been deployed to encourage the hesitant, the slow and the complacent. From dating app bonuses to donuts, lotteries to laminated vaccination cards — when do incentives become coercive? Tempting little lagniappes to reward vaccination include free popsicles, milkshakes and hot dogs; free Budweiser if 70 percent of Americans are vaccinated by the Fourth of July; free Krispy Kreme donuts every day for a year. But daily donuts seem incongruous when obesity is a comorbidity for COVID. And was the person who came up with the idea of offering free ‘joints for jabs’ actually high?

Some of the rewards are substantial. United Airlines is running the ‘Your Shot to Fly’ sweepstakes, giving away 30 pairs of free flights to vaccinated customers. The state of California’s ‘Vax for the Win’ $116.5m lottery is the most generous of multiple cash giveaways in the US. There are even scholarships to public universities. And this is where we hit problems.

High risk from COVID is both age-stratified and associated with identifiable clinical conditions, which means some nuance in who is incentivized, and how, should be seen as tolerable. ‘Giving homeless people $20 to encourage them when they are at high risk from COVID is acceptable in my opinion,’ says Dr Stefan Baral, an associate professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, ‘but enticing a student with a scholarship scares me the most.’

Baral would rather see young people turn to pediatricians for individual advice. Yet in Toronto, children as young as 12 have been offered free ice cream for vaccines and do not need parental consent. Baral agrees that this ‘deviates into coercion’, particularly as he is not comfortable with emergency use authorization for 12- to 15-year-olds. The risk calculus of the vaccine itself is not yet clear for the young; for example, Israeli data suggests a post-vaccine link with myocarditis, particularly in young men. Should the young be persuaded and bribed to have an intervention which might do them more harm than good?

The WHO’s Technical Advisory Group on Behavioral Insights and Sciences for Health is chaired by the celebrated behavioral economist Cass Sunstein, who has suggested overcoming ‘coronavirus vaccine phobia’ by tackling issues of convenience, complacency and confidence.

Uber and Lyft have offered rides to vaccination centers, which overcomes inconvenience. Targeting ‘complacency’ is more provocative because this rests upon persuading people that their personal mortality risk from the virus is not low. Well, sometimes the risk is low, and the public knows it. The resulting disconnect has been evident at least since an infamous paper advised the UK government that ‘a substantial number of people still do not feel sufficiently personally threatened; it could be that they are reassured by the low death rate in their demographic group’ and recommended that ‘the perceived level of personal threat needs to be increased among those who are complacent, using hard-hitting emotional messaging’.

Sunstein suggests offering ‘vivid warnings, including truthful narratives about deaths and serious illness among those who are young, healthy and tough’. But the young, healthy and tough rarely fall prey to COVID. In a dishonest democratization of risk, politicians, scientists and media have sometimes overstated its danger.

Tactics to breed social conformity range from innocuous ‘I’ve been vaccinated’ social media stickers and hashtags to the serious suggestion from the general secretary of the UK’s Association of School and College Leaders that ‘peer pressure’ should be leveraged to encourage vaccine uptake in high schools, a complete reversal of the usual anti-peer pressure, anti-drug message. Dr Jackie Cassell of the University of Sussex, a public health specialist and keen vaccine advocate, was disapproving when we spoke: ‘It plays with fire when you use peer pressure in schools. Peer pressure undermines trust in the long term. This could turn people against the vaccine which, with boosters, is going to be a marathon, not a sprint.’

‘Confidence’ is the thorniest barrier to overcome.Vaccinations have been organized in mosques and cathedrals, and encouraging messages issued from religious leaders, as UK behavioral scientists recommended that using community champions and faith leaders would promote confidence. In an audacious move, Brazil leapfrogged the faith leaders and commissioned God himself to promote the vaccine. The words ‘Vaccine Saves’ were projected onto Rio de Janeiro’s Christ the Redeemer statue as vaccine acolytes in white T-shirts and face masks raised a single-arm salute underneath.

Cass Sunstein recommends the use of endorsements from high-profile ‘validators’, and we have seen celebrities, politicians, world leaders, even royal post-vaccination selfies on social media. Are they doing this independently, or is public health messaging effectively being outsourced by government, as Sunstein proposed?

The UK Cabinet Office told me that the majority of the influencers that work with the government are not paid, as they recognize the importance of communicating health guidance on COVID-19. (Of course, that means some are paid.) In the US the public relations company Main Street One contacted celebrities, offering to pay them to promote vaccines. ‘I’m reaching out to share a paid partnership opportunity to share your voice about what the COVID vaccine means to you,’ they wrote. ‘Can you use a personal story to explain why you’re blocking out misinformation around the COVID vaccine and prioritizing the health of your community? Why are you confident that vaccines are both safe AND effective?’

Once the ethical bedrock of modern medicine, informed consent seems lost among the flood of incentives and coercion. Baral was clear that fear, social disapproval and significant incentives will all affect informed consent. He showed me a Health and Human Services (HHS) document regarding informed consent in research settings, which states that ‘payment for participation could present an undue influence, thus interfering with the potential subjects’ ability to give voluntary informed consent’. Is accepting a vaccine authorized for emergency use the same as ‘research’? No, but the current confusion suggests a ‘murky’ and ‘unprecedented’ step, according to Baral.

A more concerning tactic has been the application of negative pressure to achieve social conformity. The vaccine-resistant have been called ‘Covidiots’, ‘granny killers’ and, lately, ‘refuseniks’. Tony Blair said recently that it was ‘time to distinguish’ between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated: substitute race or another protected characteristic and this is an ugly look. The Israeli newspaper Haaretz described ultra-Orthodox Jews who do not follow the state’s vaccination rules as ‘COVID insurgents’ and ‘terrorists’ in starkly obvious bio-political language.

The implications are obvious: the vaccinated are clean and safe; the unvaccinated are unclean, unsafe, worthy of ridicule and exclusion. The writer Nick Cohen predicts a period of ‘class and racial strife’ and observes ‘it is only a matter of time before we turn on the unvaccinated’. Such a narrative of dehumanization is a serious threat to weigh against encouraging vaccines and adherence to lockdowns.

‘Behavioral psychologists focus on what you can get people to do, on short-term issues of behavior, not long-term issues of trust,’ says Dr Jackie Cassell. In the haste to bring a speedy resolution to a pandemic, to fast forward to a happy ending, what might happen to long-term confidence in public health messaging, including future vaccination programs? Emergency recourse to oversimplified pressure might not be the best solution for the unsure, who may be more likely to benefit from an in-depth conversation with a healthcare provider than from a cash prize.

Fear has created a morality play where heavy-handed get-the-shot tactics are privileged over the development of long-term trust. While the current pandemic may necessitate a quick-fix approach, the long-term objectives of improving vaccine confidence and overall trust in medical science must not be lost. More threatening still, dehumanizing tactics to deter anti-vax sentiment will divide us.

Some will rush, arms outstretched and sleeves rolled up, toward syringes and sweets. Some will hang back, deterred by an eerily hard sell. In the desperate desire to end the Horrible Story of the COVID-19 Pandemic, are we rushing toward a conclusion without being certain of our priorities?

Laura Dodsworth’s A State of Fear: How the UK Government Weaponized Fear During the COVID-19 Pandemic is published by Pinter & Martin ($18). This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2021 World edition.