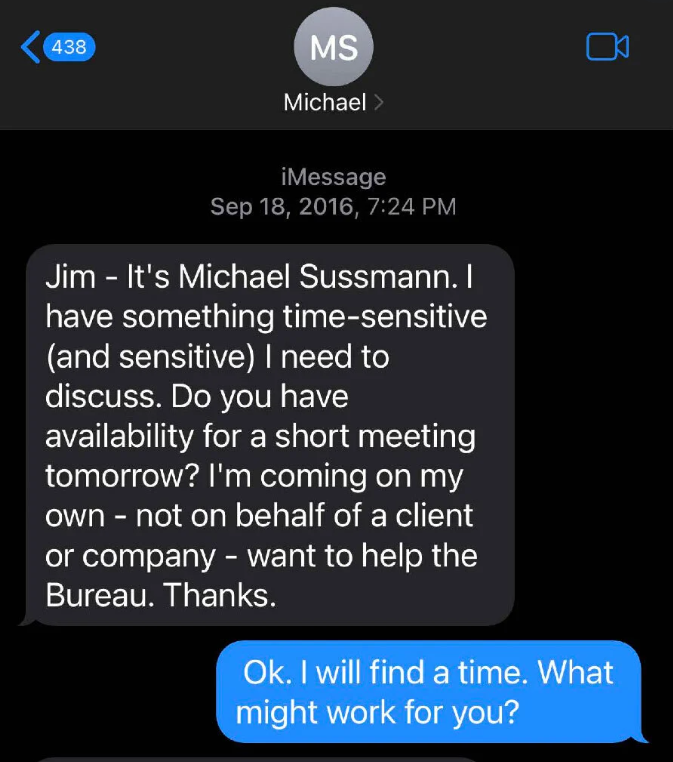

Michael Sussmann, a senior lawyer for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign, is currently on trial for lying to the FBI. The allegation is straightforward. As the election approached, Sussmann texted his old friend and fellow attorney, James Baker, requesting a brief, urgent meeting. Baker was the FBI’s top lawyer and Sussmann was a partner at Clinton’s election-law firm. They were friends from their days together at the Department of Justice and continued to know each other socially. According to the indictment, Sussmann told Baker he was coming solely to help the Bureau and not on behalf of any client.

To prove his case, Special Counsel John Durham and his team must show two things:

- Sussmann lied when he said he wasn’t representing a client in that meeting; and

- Sussmann’s lie had the “potential” to affect the FBI’s investigation. (According to the law, the lie need not actually affect the investigation; it need only have the potential to do so.)

Sussmann’s defense is to toss back the ol’ kitchen sink. “I didn’t lie. You can’t prove I lied. I had no reason to lie. And even if I lied, it really didn’t matter to the FBI.” That defense has two aims: create confusion for the jury and drag in the name of Donald Trump, for jurors in a city that voted almost unanimously for Hillary and undoubtedly loathe the former president. What Sussmann hopes for, in other words, is “jury nullification,” where the jury believes the crime has been proven but disregards the evidence and votes “not guilty.” That’s really Sussmann’s only chance.

What happened in court on Thursday should clinch the case for Durham, if the jury is fair-minded. The prosecution put on its star witness, James Baker. Baker’s obvious reluctance to testify against Sussmann makes his testimony all the more convincing. And that testimony is damning. With Baker on the stand, the prosecution introduced a text message he received from Sussmann, asking for a meeting the next day. The message is catastrophic for Sussmann’s claim he told Baker he had a client. He said, in writing, that he didn’t have one.

The key words here are “I’m coming on my own — not on behalf of a client or company — want to help the Bureau.” Although Baker did not take notes during the meeting, he testified Thursday that he is “100 percent certain” that Sussmann repeated that claim at the very beginning of their meeting. Afterwards, Baker spoke with senior FBI colleagues, including Director James Comey, and repeated what his guest had said, “Sussmann had no client.” He was simply being a good citizen when he brought some thumb drives and papers to the Bureau.

The final nail in Sussmann’s coffin is that he actually had two clients: the Clinton campaign, and a computer expert, Rodney Joffe, who expected to be named cyber-security czar in the Clinton administration. Sussmann seems to have billed Clinton his time for the meeting, but Durham’s team will have to convince the jury that he did so. They will also want to reinforce Baker’s recollections with testimony from FBI officials who met with Baker immediately after the Sussmann meeting and were told that there was no client.

The second element of the crime is that Sussmann’s lie actually mattered. Again, Baker’s testimony is crucial — and it is all the more convincing because Baker was clearly reluctant to provide it. The FBI’s general counsel testified that 1) he would not have met with Sussmann had he known the attorney was coming for a client, and 2) the Bureau’s assessment of any information Sussmann provided would have been profoundly affected had they known it came from the Clinton campaign, which had a direct interest in tying Trump to Russia, showing that the FBI was investigating those ties, and publicizing that investigation in the media before the election.

All the rest is icing on the cake for Durham. The danger is slathering on too much icing could conceal the cake. The prosecution team, led by Andrew DeFilippis, has shown the jury that Sussmann’s information, which seemed to connect Trump with Russia’s Alfa-Bank, was only meaningless spam. The FBI’s cyber experts reached that conclusion within a day or two, though their finding didn’t stop the FBI from spending years on their investigation, the Democrats from publicizing the bogus ties and investigating them for two and a half years, or friendly media from trumpeting the FBI’s fruitless investigation. That broader impact shouldn’t matter to the crime Sussmann is charged with, but it does go to his motive for lying. What matters is that the lie affected the Bureau’s investigation.

Sussmann’s motive, of course, was to damage Trump before the election. That’s why he wanted the meeting so urgently. The New York Times already had the story about Trump and Alfa-Bank (because Clinton’s team gave it to them.) The paper was reluctant to run the story without more evidence, but they would definitely run a story that “the FBI is investigating this connection” since that did not require any confirmation of the underlying connection.

Friday’s testimony by Clinton campaign manager Robby Mook confirmed that the false information was fed to the media with Hillary’s explicit permission. Mook says he didn’t know at the time if that information was true or false. Perhaps he didn’t, but other campaign officials did. After all, it was Hillary’s people who created the fable. It was Clintonista Rodney Joffe who tasked the cyber experts at Georgia Tech to go through the computer data he gave them and come up with sometime — anything — that created an “inference” that Trump was secretly communicating with a Russian bank. Moreover, it is simply inconceivable that a disinformation campaign costing this much, involving this many players, and expected to have such far-reaching consequences could be conducted without authorization from the candidate or her top aides.

The goal was always to smear Trump and help elect Hillary. That’s exactly what Sussmann doing that day in James Baker’s office. He was trying to generate an FBI investigation that could then be widely reported, to Trump’s detriment. That’s what the Bureau’s director, James Comey, was doing a few months later when he gave President-elect Trump a sketchy briefing about Christopher Steele’s dossier and the “pee tapes,” just before the Bureau illegally leaked news of that investigation to the press. Once again, the press already possessed the underlying allegations but were unwilling to run them without confirmation. Since the dossier was false, that confirmation would never come. But an avalanche of stories and investigations did come after the FBI leaked that it was investigating.

Returning to the Sussmann trial, the defendant’s only hope now is a biased jury. To let Sussmann off the hook, the jury must discard Sussmann’s explicit text message, the testimony of James Baker and the FBI officials he spoke with after the meeting, and the Bureau’s subsequent investigation of the materials Sussmann gave them. We now know those materials were concocted by the Joffe’s cyber-team to “create the narrative and inference” that Trump was secretly communicating with a Russian bank. That inference was false, and the team that created it not only knew it was false, they knew any sophisticated cyber analyst could figure it out quickly. No matter. They wanted to publicize an FBI investigation. And they did.

Durham has not charged Sussmann with being part of a larger conspiracy. Not yet. But Durham has presented a lot of evidence that such a conspiracy (or “joint venture”) existed. It remains to be seen if Durham plans to level those charges, which would target one of the largest, nastiest dirty tricks in modern American politics. If Sussmann is convicted, he will have powerful incentives to tell Durham how that conspiracy worked and provide an insider’s testimony about the participants. If Sussmann is not convicted, Durham’s path forward is unclear.

Those are high stakes, which is why Sussmann’s trial is so important. The attorney may be charged with only a single count, but detonating that charge would produce a devastating explosion.