The return of Mencius Moldbug is a timely one. Across Europe, after all, people have begun to share his anti-democratic sentiments. British liberals have spent years attempting to undermine the result of the 2016 referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU. American liberals have spent years looking for excuses to impeach Donald Trump and countermand the results of the 2016 Brexit referendum. Yes, it is somewhat ironic that three-and-a-half years after the retirement of Mencius Moldbug from blogging, anti-democratic sentiments tend to be heard from the left and populist sentiments tend to be heard from the right.The brief flourishing of neoreaction, otherwise known as NRx, otherwise known as the Dark Enlightenment, feels like a world away. From 2007 to 2014 — with a short retirement post following two years later — Mencius Moldbug, the pen-name of a Californian programmer named Curtis Yarvin, published lengthy, eccentric, elliptical essays on his blog Unqualified Reservations, which denounced democracy and advocated ‘neocameralism’, an elitist ideology which held that states should be run more or less like corporations, with a small class of shareholders electing a CEO.Moldbug argued that progressive ideas based on a fallacious belief in human equality were dominant in NGOs, the media, the universities and bureaucratic institutions which he called, collectively, ‘the Cathedral’. While leftists had built power through these institutions, he argued, conservatives had grumbled ineffectually. ‘One pathology of our age,’ he wrote:‘…is a childlike credulity in the magical efficacy of complaint. Don’t complain, build. We have done well at complaining; so what? What have we built?’Neocameralism was Moldbug’s alternative, which required no popular consent but the seizure of power. Somehow, though, Moldbug’s readership did not include people able or willing to seize power and his blogposts began to peter out. Oddly, his ideas pierced the mainstream at the point where his blogging had become less frequent. Nick Land, an English philosopher who had once been notorious for his ideas of hyper-technologization, synthesized Moldbug’s concepts in a series of essays that promoted what he called ‘the Dark Enlightenment’. ‘The Dark Enlightenment’ was premised on its opposition to ideas of human equality: racial equality, sexual equality and class equality. This, it tended to promote immigration restrictionism, moral traditionalism and political elitism.For a while, ‘neoreactionary’ blogs were ubiquitous. Two things led to their decline. Firstly, the rise of Donald Trump led the mainstream right towards populism, not elitism. Conservatives became bottom-up class warriors defending the homespun wisdom of the American worker. Secondly, the far right, or what became the alt-right, began to find neoreaction far too snobbish and deracialized. The likes of Moldbug and Land might have believed in racial inequality but it was not in the sense of white supremacism but a sense that found high-IQ Jews and Asians more collegial the average white American. This failed to rouse the tribal impulses that made a Richard Spencer more attractive than a Mencius Moldbug.So, why has Moldbug reappeared, with a new series of essays at The American Mind? Firstly, it is to reclaim the dissident right label from ‘alt-right’ neo-fascists. Secondly, it is because Moldbug and his publishers at the Claremont Institute can see that Donald Trump, even if he wins a second term, will not do much to shift cultural trends away from progressivism. Moldbug, in fact, predicted something like Donald Trump in a 2010 debate with the traditionalist blogger Lawrence Auster, in which he argued that it was pointless for right-wingers to pursue democratic power. ‘I would rather have 10 people, all in possession of the same absolute truth,’ he wrote:‘…than 10 million Tea Partiers who agree on nothing but glittering lies and myths. For my 10 is a viable government in exile — if they somehow gained power, they would keep it — whereas your ten million have no real collective identity at all. Even if they grow to a hundred million and elect all the politicians in Washington, actual power will elude them, the bureaucrats will wrap them around their fingers, and they will evaporate, disappear, and become jokes, like all 20th-century American conservative movements.’Pro-Trump intellectuals like Michael Anton, recently found flirting with another relatively non-racist, non-anti-Semitic dissident right movement in his review of Bronze Age Pervert’s book Bronze Age Mindset, fear the Trumpism evaporating, disappearing and becoming a joke in a haze of ‘lock her up’ memes and QAnon paranoia and are attempting to lay the groundwork for a post-Trump right which can more radically and permanently alter the progressive character of American culture without descending into violent racialism.It is true that conservatives have been more successful at winning political power than at using it, and Moldbug is correct that winning power is almost meaningless if it is only power achieving for four years at a time. His essay for The American Mind is an attempt to explain why even seizing the presidency did little to change the course of American life. In essence, it is an introduction to his idea of the Cathedral, about which Moldbug writes:‘…some mysterious force seems to ideologically coordinate this system. All these prestigious institutions, though organizationally quite separate, seem to magically agree with each other. When they change their minds, all change together, in the same direction.’The progressive aptitude for sacralizing memes is undeniable, as anyone who has observed discourse surrounding transgenderism must accept. A decade ago, ‘is a trans woman a real woman’ was barely a question. Now it is unquestionable.Trying to apply his concept to the American political system, Moldbug writes that Congress: ‘…operates as a “defeat device” against real democracy…‘Congress has two sources of legislative input: activists and lobbyists. The activists come for power; the lobbyists, money.‘Activists are Democrats; lobbyists are whores.’This is funny, and there is at least some truth to it, but it is also something of a coping mechanism for conservatives who don’t want to accept that their purported savior is an enormous egotist surrounded by an army of grifters who had little interest in pursuing real change to begin with. Change has to become at home.A second more fundamental question for the Moldbug project is, power to what end? For someone who appears as if he could write 10,000-word shopping lists, Moldbug is strangely reticent on what its point should be. I suspect that he explained its primal urge most lucidly in his debate with Auster, where he said:‘My concern is that this system is degrading monotonically. In the lives of those now living, it provided A or at least A- service. Furthermore, we know exactly what C government, D government, and F government look like, because we see them all around us in current history. I do have posterity, and I want to secure the blessings of good government for them. I don’t want to see them raped and killed by human orcs.’I do not think he was just talking about literal rapists and murderers, but also about communists taking his property and activists meddling with his business. Still, this is just libertarianism baked into a different shell – a Whiggish attitude towards elite innovation in a reactionary crust. Moldbug is fond of using ‘pill’ metaphors. He liked ‘the red pill’, to refer to unpopular truths, and now he likes ‘the clear pill’, to refer to clearing one’s mind of biases. Well, medication has its uses of course, but at its worst it can offer quick, superficial solutions to deep underlying problems. This might sound like an absurd complaint to make of Moldbug, who explores the roots of power in agonizing detail, but knowing what to do with power demands knowing it means to be a social animal and that is especially relevant to Moldbug and his Silicon Valley admirers as they analyze new means of transforming our way of life and, indeed, man itself.

Oddly, his ideas pierced the mainstream at the point where his blogging had become less frequent. Nick Land, an English philosopher who had once been notorious for his ideas of hyper-technologization, synthesized Moldbug’s concepts in a series of essays that promoted what he called ‘the Dark Enlightenment’. ‘The Dark Enlightenment’ was premised on its opposition to ideas of human equality: racial equality, sexual equality and class equality. This, it tended to promote immigration restrictionism, moral traditionalism and political elitism.For a while, ‘neoreactionary’ blogs were ubiquitous. Two things led to their decline. Firstly, the rise of Donald Trump led the mainstream right towards populism, not elitism. Conservatives became bottom-up class warriors defending the homespun wisdom of the American worker. Secondly, the far right, or what became the alt-right, began to find neoreaction far too snobbish and deracialized. The likes of Moldbug and Land might have believed in racial inequality but it was not in the sense of white supremacism but a sense that found high-IQ Jews and Asians more collegial the average white American. This failed to rouse the tribal impulses that made a Richard Spencer more attractive than a Mencius Moldbug.So, why has Moldbug reappeared, with a new series of essays at The American Mind? Firstly, it is to reclaim the dissident right label from ‘alt-right’ neo-fascists. Secondly, it is because Moldbug and his publishers at the Claremont Institute can see that Donald Trump, even if he wins a second term, will not do much to shift cultural trends away from progressivism. Moldbug, in fact, predicted something like Donald Trump in a 2010 debate with the traditionalist blogger Lawrence Auster, in which he argued that it was pointless for right-wingers to pursue democratic power. ‘I would rather have 10 people, all in possession of the same absolute truth,’ he wrote:‘…than 10 million Tea Partiers who agree on nothing but glittering lies and myths. For my 10 is a viable government in exile — if they somehow gained power, they would keep it — whereas your ten million have no real collective identity at all. Even if they grow to a hundred million and elect all the politicians in Washington, actual power will elude them, the bureaucrats will wrap them around their fingers, and they will evaporate, disappear, and become jokes, like all 20th-century American conservative movements.’Pro-Trump intellectuals like Michael Anton, recently found flirting with another relatively non-racist, non-anti-Semitic dissident right movement in his review of Bronze Age Pervert’s book Bronze Age Mindset, fear the Trumpism evaporating, disappearing and becoming a joke in a haze of ‘lock her up’ memes and QAnon paranoia and are attempting to lay the groundwork for a post-Trump right which can more radically and permanently alter the progressive character of American culture without descending into violent racialism.It is true that conservatives have been more successful at winning political power than at using it, and Moldbug is correct that winning power is almost meaningless if it is only power achieving for four years at a time. His essay for The American Mind is an attempt to explain why even seizing the presidency did little to change the course of American life. In essence, it is an introduction to his idea of the Cathedral, about which Moldbug writes:‘…some mysterious force seems to ideologically coordinate this system. All these prestigious institutions, though organizationally quite separate, seem to magically agree with each other. When they change their minds, all change together, in the same direction.’The progressive aptitude for sacralizing memes is undeniable, as anyone who has observed discourse surrounding transgenderism must accept. A decade ago, ‘is a trans woman a real woman’ was barely a question. Now it is unquestionable.Trying to apply his concept to the American political system, Moldbug writes that Congress: ‘…operates as a “defeat device” against real democracy…‘Congress has two sources of legislative input: activists and lobbyists. The activists come for power; the lobbyists, money.‘Activists are Democrats; lobbyists are whores.’This is funny, and there is at least some truth to it, but it is also something of a coping mechanism for conservatives who don’t want to accept that their purported savior is an enormous egotist surrounded by an army of grifters who had little interest in pursuing real change to begin with. Change has to become at home.A second more fundamental question for the Moldbug project is, power to what end? For someone who appears as if he could write 10,000-word shopping lists, Moldbug is strangely reticent on what its point should be. I suspect that he explained its primal urge most lucidly in his debate with Auster, where he said:‘My concern is that this system is degrading monotonically. In the lives of those now living, it provided A or at least A- service. Furthermore, we know exactly what C government, D government, and F government look like, because we see them all around us in current history. I do have posterity, and I want to secure the blessings of good government for them. I don’t want to see them raped and killed by human orcs.’I do not think he was just talking about literal rapists and murderers, but also about communists taking his property and activists meddling with his business. Still, this is just libertarianism baked into a different shell – a Whiggish attitude towards elite innovation in a reactionary crust. Moldbug is fond of using ‘pill’ metaphors. He liked ‘the red pill’, to refer to unpopular truths, and now he likes ‘the clear pill’, to refer to clearing one’s mind of biases. Well, medication has its uses of course, but at its worst it can offer quick, superficial solutions to deep underlying problems. This might sound like an absurd complaint to make of Moldbug, who explores the roots of power in agonizing detail, but knowing what to do with power demands knowing it means to be a social animal and that is especially relevant to Moldbug and his Silicon Valley admirers as they analyze new means of transforming our way of life and, indeed, man itself.

Is this Mencius Moldbug’s moment?

The neoreactionary blogger has resurfaced with a new essay

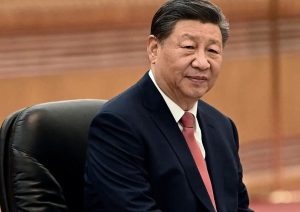

Curtis Yarvin aka Mencius Moldbug

The return of Mencius Moldbug is a timely one. Across Europe, after all, people have begun to share his anti-democratic sentiments. British liberals have spent years attempting to undermine the result of the 2016 referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU. American liberals have spent years looking for excuses to impeach Donald Trump and countermand the results of the 2016 Brexit referendum. Yes, it is somewhat ironic that three-and-a-half years after the retirement of Mencius Moldbug from blogging, anti-democratic sentiments tend to be heard from the left and populist sentiments tend to be heard from…