Anyone could see that Joe Biden veered off-script during his big speech in Poland. “For God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power,” he said of Vladimir Putin, which sounded a lot like a cry for regime change. Luckily for him, though, and perhaps for world peace, Leon Panetta, a former secretary of defense under Barack Obama, was on hand to explain the comment away: “I happen to think that Joe Biden — you know, he’s Irish — really has a great deal of compassion when he sees that people are suffering.”

To be sure, to be sure. Still, even if Biden’s threat to Putin can be wholly attributed to a Gaelic jig playing in his head, the fallout has been the same. His staff promptly “walked back” the remark, while Biden was said to have cast a shadow on an otherwise successful European trip.

The Putin comment was a kind of flash-encapsulation of the entire Biden approach to the Ukraine crisis. It was bracing yet confusing, earnest yet reckless, sharp on the surface while concealing a more complex and calculated reality underneath — from a president who can’t seem to stop betraying his authority with an endless stream of unhelpful ad-libs.

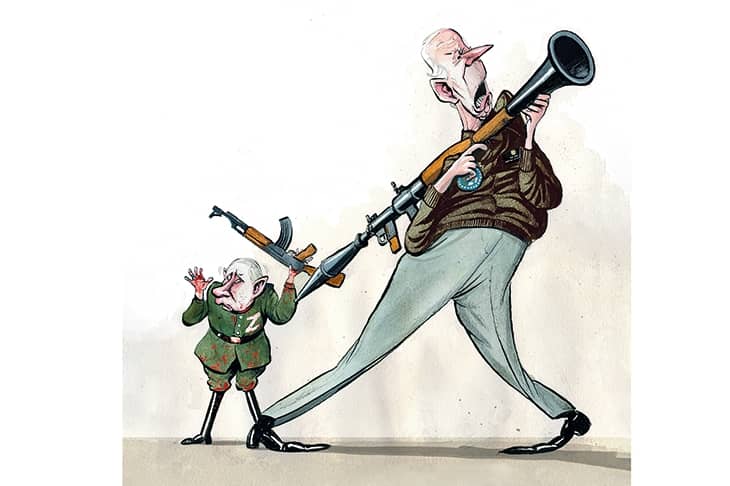

With much now riding on how well America handles the most perilous geopolitical situation for at least a generation, we see again an immutable principle of global politics at work, one that ranks right up there with “never get involved in a land war in Asia.” It is this: Biden will find a way to undermine himself. At least his apparent regime change demand had the virtue of making sense. His other gaffes on the same trip were more muddling, such as a vague threat to respond “in kind” if Russia used a chemical weapon in Ukraine, implying that the United States might unleash sarin gas over eastern Europe. There was also the moment when he seemed to tell the 82nd Airborne that they would soon be deployed in Ukraine.

All these slips can be dismissed as just Biden being Biden. He’s never been famous for his silver tongue. The Biden White House has become pretty adept at correcting their leader’s disastrous verbosity. But that leaves an odd dynamic: what America’s commander-in-chief says isn’t necessarily final — or even remotely coherent. It’s similar to the way things work in autocracies: the real intent must be deciphered. At a press conference on Monday, Biden was caught holding a cheat sheet marked “Tough Putin Q&A Talking Points.” The document instructed him to say that by calling for Putin to be removed he was “not articulating a change in policy.”

But unlike his predecessor Donald Trump, Biden the man does not seem to disturb the machinery of his government — whose approach to the Ukraine crisis has in recent weeks been strikingly sensible. As hawks like Senator Mitt Romney dust off the 2003 War On Terror quote manuals, and as Volodymyr Zelensky pleads for more help (in the form that could bring NATO into open conflict with Russia), Biden’s administration has been steadfast that — while America supports Ukraine, is willing to supply masses of arms and technology, and wants to hurt Russia — no troops will be deployed in Ukraine. “We will not fight the third world war,” said Biden, by which he clearly means a nuclear war. In this, he has demonstrated a quality often lacking in foreign policy discourse: imagination. Biden knows this war could worsen in ways we don’t even want to think about, and that we must avoid such an outcome at all costs.

This is the Biden who was chastened by Iraq, who tried to convince Obama not to intervene in Libya, who rightly perceived that the war in Afghanistan could not be won. Biden is seen as a member of the establishment — and he is — but his instincts on foreign policy are much less hawkish than your garden-variety Brookings Institution scholar. The Biden way is to hammer together an alliance of nations that will stand strong against threats without ever firing the first shot. He’s a multilateralist at his core but one who understands military limits and prefers deterrence to violence.

This was on full display with the recent brouhaha over the MiG-29 aircraft. Ukraine had asked for the jets, Poland had offered to provide them, yet it was America that ultimately killed the transfer. Subsequent reports indicated that Biden had fallen back on what was essentially a cost-benefit analysis. The logistics of moving the MiGs over the Polish border to Ukraine would have been difficult, the jets wouldn’t have lasted long against Russian anti-air assets, and — most importantly of all — NATO would have been placed in a dangerously provocative position vis-à-vis Russia. Insisting that the war not be expanded, Biden made the right choice.

The MiG decision wasn’t especially surprising, given that the administration had previously been chary about sending anti-ship missiles to Ukraine. But it was remarkable when you consider just how much pressure the president was under. Every talking head on CNN, every Instagram model who woke up yesterday to discover she was an avid Kremlinologist, was demanding he hand over those jets. That he resisted suggests his caution is innate, that he really is more calculating on foreign policy than his public persona would suggest. It also suggests a certain useful “strategic ambiguity.” The gap between what Biden says and what his administration does leaves plenty of room for Russian doubt.

There is evidence that Biden’s cautious approach is working. An invasion of a sovereign nation is a wretched thing. Yet Russia’s gruesome attack on Ukraine seems to be going about as well as it could be for the United States. The Russians are bogged down. Kyiv and even Mariupol have yet to fall. The Ukrainians have rallied global support (there are more blue and yellow flags in Washington, DC right now than red, white and blue ones) without NATO firing a shot. The western nations, so tested in recent years, seem as united as they’ve been since 9/11. Biden’s Poland speech was actually pretty good — at least for as long as he kept to the autocue. He addressed the Russian people directly, saying: “You are not our enemy… This is not the future you deserve for your families and your children.” He pointed to the wide alliance of free peoples that has emerged.

But that does not mean the American public has rallied behind Biden. On the contrary, his poll ratings are hitting new lows as voters grapple with runaway inflation and other domestic difficulties. There’s also a degree to which, while Americans famously don’t care that much about foreign policy, they are unimpressed with the way Biden the gaffe-machine has gone about the world stage. A majority of Americans may have wanted him to end the unwinnable war in Afghanistan, but the botched evacuation in August was a national embarrassment. It was also the moment when Biden’s job approval ratings started really tanking.

Not everyone forgets Biden’s problematic history when it comes to Russia and Ukraine. Let’s start with the infamous Russia “reset” fiasco of 2009. The episode, which saw then-secretary of state Hillary Clinton present a button to the Russian foreign minister that was supposed to read “reset” in Cyrillic but instead translated to “overload,” can’t be laid solely at Biden’s feet. But he did play a major role in articulating the “reset” policy.

That “overload” mistranslation ended up being eerily accurate. After the button was pushed, Russia proceeded to invade Syria, meddle in Libya, annex Crimea and even, if you believe it, launched an intervention into the 2016 American presidential election. Russian aggression might not have been a threat to the US, but it did distract the Obama administration as it tried to pivot to Asia.

There’s also the matter of the 2014 Maidan revolution, which overthrew Ukraine’s pro-Russia government and prompted the Crimea invasion. Maidan was egged along by the United States, particularly the famously brash assistant secretary of state Victoria Nuland, who went to Kyiv during the protests and distributed sandwiches. But she was so undiplomatic that she managed to offend not just Russia but the entire European Union.

Naturally, when Biden was elected, he brought Nuland back into the State Department and gave her a promotion. No coincidence there: it was Biden who had led the response to the Maidan uprising in Ukraine. He visited Kyiv in 2014, talked down the Russians and met repeatedly with the new government to help it find its legs. Biden was blunt with the Ukrainians too, telling them at one point in his delicate way that they couldn’t be seen as a “basket case’”or they’d be “screwed and left at the mercy of Moscow.” But his overall message was that Washington supported Maidan and was determined to see Ukraine lean west, a contrast with the caution he shows today.

Among the most overrated terms in foreign policy is “credibility,” which is usually employed by those who want to see the American military act everywhere all the time, lest it loses “credibility” in the eyes of allies. A better word, perhaps, is “perception.” And the perception of America that Biden and others helped establish in Moscow was one of blundering arrogance, a blind giant staggering and thrashing. All the while, Putin was no doubt watching, trying to game out how much of a risk America might pose if he sent in the tanks.

It’s hard to claim that Putin invaded Ukraine because Joe Biden is president. Trump may have been a more unpredictable statesman, but he would have struggled to hold together a wide coalition against Russia. There are many other factors that pushed Putin towards his aggression, from Germany’s equivocation over sanctions to changing relations between Beijing and Moscow to Putin’s own alleged Covid cabin fever.

At the same time, it must be said that Putin wasn’t deterred by Biden, that neither the president’s realism nor his idealism seemed to matter a whit. What very likely did matter was his waffling between the two, which Putin may well have interpreted as another sign that America had gone soft.

As for Biden himself, it may be that he comes out of this crisis with a fresh glow. It’s not as if, with the even less popular Vice President Kamala Harris waiting in the wings, America has a more attractive leadership alternative. By attacking a sovereign country and horrifying the world, Putin gave Biden a rare opportunity to rally what people used to call the free world. Whether he’s physically or mentally competent enough to take this opportunity is another question.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.