The US and other western countries are faced with a dilemma: how to bring to justice a man with the blood of thousands on his hands when you have to do business with him.

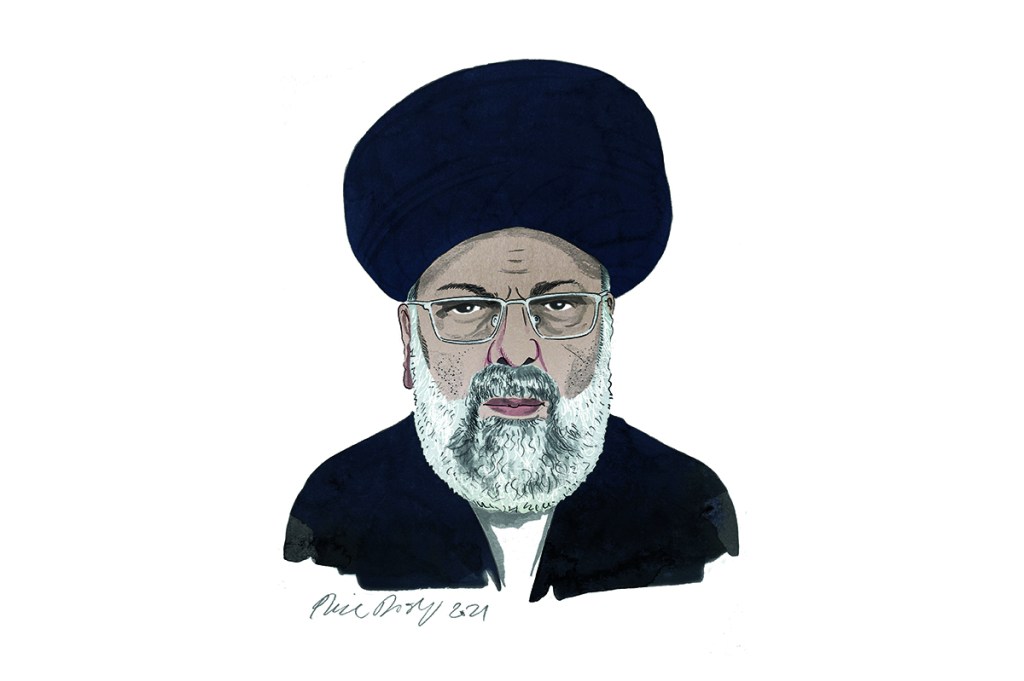

Ebrahim Raisi’s path to the presidency of Iran is strewn with corpses. He comes to office this month already under American and European sanctions for the mass murder of prisoners in 1988. Some 5,000 may have been killed, though we can only guess at the true number of dead. It was a crime against humanity in the strict legal meaning of that term. At an earlier stage in his career, Raisi is said to have personally supervised the torture of dissidents, but in the 1988 case his responsibility was bureaucratic. He was a grim fanatic, eager to carry out orders. He was — and remains — Iran’s hanging judge.

The Iranian regime has never publicly acknowledged what happened in 1988. In the early hours of a July morning, the main prisons were abruptly ordered to cut off all contact with the outside world. Visits were canceled and relatives forbidden from gathering at the prison gates. Telephone calls and letters were banned, even medicines were not allowed through. Prisoners were kept in their cells. The only visit allowed was from a delegation, turbaned and bearded, who came in an ominous convoy of black government BMWs. This was the ‘Death Committee’ of four men who would decide the prisoners’ fate. Raisi was one of its members. He was 27, the committee’s most junior official, and he held the power of life or death over a legion of the regime’s enemies.

Iran’s ruler, the Ayatollah Khomeini, had issued a secret fatwa, or religious ruling, against the rebel People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran, the PMOI. It said they were to be executed as moharebs, ‘those who wage war on God’. The Death Committee zealously carried out the fatwa’s instruction not to ‘hesitate, nor show any doubt or concerns with detail’. Hearings often lasted only a couple of minutes. Prisoners were brought, blindfolded, from the cells and asked their affiliation. If the answer was ‘Mojahedin’, the hearing was over. They would be taken to the gallows where a crane hoisted them slowly up by their necks — the Iranian method of hanging does not use a trapdoor. It was a slow and agonizing death. The procession of victims was such that the overworked executioners asked for firing squads to be used instead.

Raisi was asked about the 1988 massacre during this year’s election campaign. He did not admit to membership of the ‘Death Committee’ — he has never done so — but said he had been a ‘proud defender’ of human rights and of the ‘people’s security’. It’s true that the PMOI had been waging an (ineffective) armed struggle, but those directly involved had already been executed. Many of those in jail had been arrested years earlier at street protests. Others had finished their sentences and were due for release. And after the first wave of killings was over, the Death Committee apparently got a second decree from Khomeini: to try left-wing prisoners for apostasy. These prisoners found their lives depended on how they answered cleverly crafted questions based on esoteric theology. One was: ‘When you were growing up did your father pray, fast, and read the Holy Qur’an?’ That was a trap few of the leftists understood: you could not be an apostate unless raised by an observant Muslim father. This was Europe’s medieval Inquisition reborn in modern Iran. More were sent to the gallows.

Many of the telling details in the account above come from Tortured Confessions, by Ervand Abrahamian, written more than 20 years ago when almost no one in the West was talking about the killings. He told me that careful calculation lay behind the atrocity. It was not — as some believed — a panicked reaction to the truce forced on Khomeini to end the Iran-Iraq war, which Khomeini had said was like ‘drinking poison’. This was a decision, Professor Abrahamian went on, dictated entirely by the internal dynamics of the regime, Khomeini acting to bind his true supporters together in blood and purge the half-hearted who would not safeguard his legacy. Raisi was the product of this process. He got a rapid series of promotions: chief prosecutor in Tehran, then deputy head of the judiciary, finally head of the judiciary.

In the judiciary, Raisi was once more the hanging judge. More than 600 people were sent to the gallows, often after manifestly unfair trials, in the last two years that Raisi led the judiciary. Raisi played an important part as well in the brutal crackdown on brave protesters during the Green uprising of 2009 — another reason he’s under sanction by the US. He took a leading role in the repression of the most recent protests, in 2019. Some of those arrested then have been hanged; according to Amnesty International, meanwhile Raisi granted blanket immunity to government officials and members of the security forces ‘responsible for unlawfully killing hundreds of men, women and children’ on the streets. Raisi’s election is being interpreted as the regime tilting to the hardliners — which it is — but the hardliners have always been there, keeping the machinery of the regime running (however much the West might be charmed by urbane figures like the foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif).

The Iranian opposition says that another uprising is on the way. As I write, thousands of oil workers in the south of the country are on strike for higher wages. The regime will not need to be reminded that the Iranian revolution began with strikes by oil workers in the 1970s. The former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, another hardliner, has said that Iran is ‘on the verge of explosion’. What’s happening now has yet to become mass street protest but if it does, everything we know about Raisi’s history and personality suggests he won’t hesitate to spill blood.

As a young prosecutor just out of the seminary, aged 19 or 20, he is accused of watching and directing the torture of prisoners. Farideh Goudarzi told me she was one of his victims. She spoke to me over a video link, a woman in her sixties wearing a headscarf. From time to time, she held up black and white photographs of a husband and brother who, unlike her, did not survive Raisi’s attentions in Iran’s revolutionary prisons.

She was arrested at the age of 21, almost nine months pregnant, and held in the court complex in Hamadan, where Raisi was the provincial prosecutor. Day and night, she told me, she could hear the screams of people under torture. When her turn came, she was taken to a windowless room underground. The corridors, and the room itself, were splattered with blood. There were lengths of electrical cable on the floor and a small bed with ropes at either end. She knew what this was for: prisoners would be restrained face down on the bed and beaten on the soles of their feet with the cables. Her husband had been tortured to the point of insanity in this way, before he was taken out to the courtyard and hanged with four other men. She was too pregnant to lie on her stomach so they made her sit on the bed, slapping her and using the cables to beat her hands.

Seven or eight people were there, among them a young man dressed in dark clothes who never strayed from the corner of the room and who betrayed no flicker of emotion as the beatings went on. Goudarzi assumed he was ‘another one of the torturers’ but she learned later that this was Raisi, the Hamadan prosecutor, who was in charge of everything that was happening to her. ‘Even after decades have passed, I can still see his face.’ Her son was born in prison, two weeks after her arrest. One day, the guards came to get her from the prison hospital and took her back to the torture cell. Raisi stood in the doorway and watched as a guard picked up her sleeping son and dropped him on the floor. Mother and baby screamed. ‘Raisi seemed pleased.’ There was to be a second, horrific occasion when her baby son was hurt. This time, the guards struck him ‘on his back’ many times over the course of a six-hour interrogation. Raisi watched in silent approval, she said. ‘He was merciless.’

It will be revealing to see whether the US allows President Raisi to travel to the United Nations General Assembly in New York while he is under sanction. Either way, the US will have to deal with him — probably indirectly — to get a nuclear deal. His status as a ferocious hardliner makes such a deal neither more nor less likely. He will have some influence but decisions rest largely with the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, and with the Revolutionary Guards. The regime needs the money a new deal would provide. The mullahs will do what they have to to ensure their collective survival. The nuclear negotiations will play out in split screen with international attempts to bring President Raisi to justice.

The trial of a former clerk to the Death Committee, Hamid Nouri, starts soon in Sweden. He had gone to Stockholm to visit relatives but was recognized and arrested under the universal jurisdiction that some countries claim for crimes against humanity. Testimony from survivors during his trial, and from Nouri himself, is expected to provide more evidence about what President Raisi did in 1988. The international human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson told a news conference organized by the Iranian opposition that Raisi would be a test case. Heads of state have special immunity, he said, but crimes against humanity have to be punished. Former leaders have been prosecuted — General Pinochet of Chile, Charles Taylor of Liberia — but there has never been a case against a sitting head of state. Robertson hopes that western governments will put Raisi in the dock, rather than shake his ‘bloodstained hand’.

All this is theoretical until President Raisi leaves Iran for any country that claims universal jurisdiction — countries he is unlikely to wish to visit. Reza Fallahi, who survived the Death Committee, also spoke at the opposition news conference. He said that of the four members of the Committee, Raisi seemed most intent on sending people to the gallows. Fallahi is bringing a legal action against him in London and has asked the British police to investigate under universal jurisdiction. He is not optimistic. Once, he remembers, his blindfold was removed after a long torture session to see one of the prison governors standing there. The man told him not to be ‘deceived’ by western countries’ talk of human rights. ‘They would not exchange all your red blood for one barrel of black oil.’ President Raisi’s reception by western governments will reveal if that general principle still holds true.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2021 World edition.