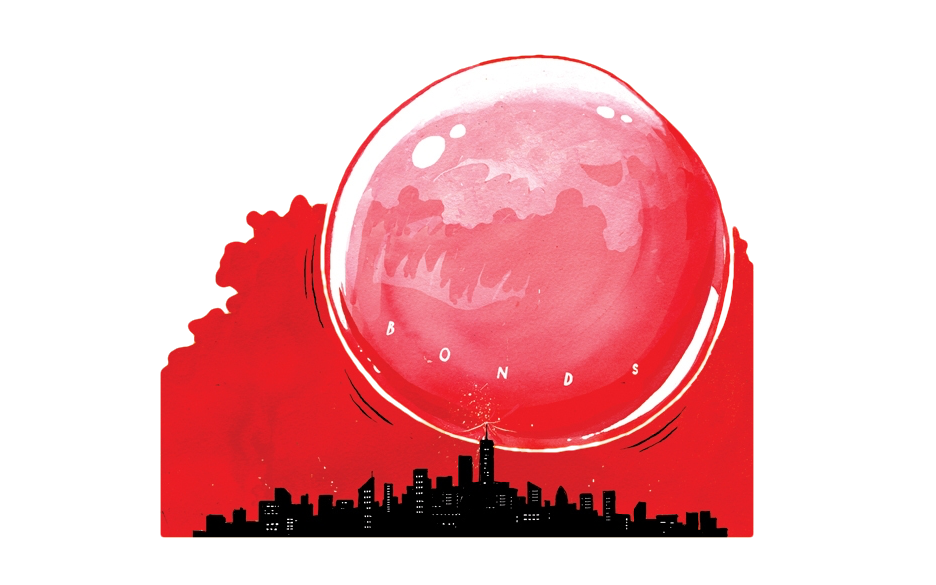

In the global market for government debt, worth an estimated $92 trillion, it amounts to little more than a drop in the ocean. The European Union this week issued the first €20 billion ($23.8 billion) of bonds to pay for its Coronavirus Rescue Fund. The money itself doesn’t amount to very much one way or another. And yet, the Commission’s president Ursula von der Leyen was surely right when she described it as a ‘truly historic day’. Why? Because, the Commission is already using it to seize control of fiscal policy, just as it used vaccine procurement to take control of health policy.

Its enthusiasts have already hailed the fund as the EU’s ‘Hamilton moment’, in a reference to the first treasury secretary of the United States, who issued bonds on behalf of the fledgling nation — both as a way of accessing some cash but also, and perhaps more importantly, as a way of binding the states together as a single country.

It has already become clear that the Commission is intent on precisely the same plan. Von der Leyen has already started a tour of EU capitals to inspect and sign off on spending plans and to make sure every last cent is accounted for. It will be clear to everyone that public spending no longer comes from a finance minister in Rome or Lisbon but from the lady in Brussels. For example, the Portuguese government, the first to have its request approved, has set out plans for electric and hydrogen trams in Lisbon, digital training for citizens and forest management.

What could possibly go wrong? Well, quite a lot as it happens. In fact, there are three big problems. First, the Commission is likely to insist on faddish projects that are popular with think tanks but don’t mean much on the ground. Next, the Common Agricultural Policy, by far the EU’s biggest budget item to date, has become notorious for corruption and gangsterism, while Brussels’s lobbying industry has now turned into a swamp equivalent to Washington. It is unlikely that all the money will be well spent. At best, most will subsidize well-connected companies, while much will simply be stolen.

Finally, while the EU has said a lot about the spending, it has been very quiet so far about the taxes that will ultimately be raised to pay for it. A slightly less well-remembered ‘Hamilton Moment’ was the whiskey rebellion of 1791-94 when George Washington had to lead an army of militiamen to put down a revolt against his treasury secretary’s tax on the spirit. Von der Leyen may not need an army, and anyway her record as German defense minister suggests it wouldn’t be nearly as well led as Washington’s, but it is unlikely the taxes she eventually introduces will be any more popular than Hamilton’s.

There was nothing intrinsically crazy about the EU controlling vaccine procurement. But, as it turned out, it didn’t have the expertise, the will or the drive to complete the task as quickly as it needed to. Likewise, there is nothing intrinsically crazy about fiscal policy being controlled by Brussels. In many ways it could be an improvement. A zone with a single currency was probably always going to need a single fiscal policy as well to make it work. But the EU has a treacherous habit of taking control of swathes of public policy without the means to deliver — and its fiscal policy could easily be as big a catastrophe as its procurement of vaccines.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.