In the space of just a few years, Britain has gone from China’s would-be best friend to part of a pact to counter it. When President Xi Jinping came to London in 2015, Downing Street pulled out all the stops. Xi stayed at Buckingham Palace, visited Chequers and signed — of all things — a cyber security agreement. The police went to extraordinary lengths to clamp down on protests by Free Tibet supporters and a Tiananmen Square survivor. Yet just six years later the UK has now joined with Australia and the US in AUKUS, a new alliance designed to check China’s power in the Pacific.

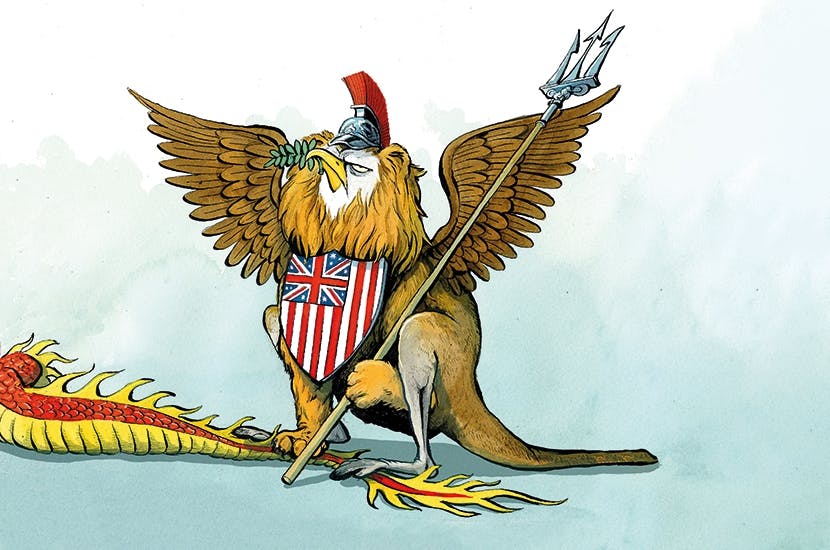

Britain is no longer trying to stay neutral in the competition between the US and China. It has firmly sided with the United States. It looks as if the contours of the next 30 years of British foreign policy have just been fixed.

The new alliance is all about mutual interest. The Aussies wanted lasting protection from China, which France could not provide, so Britain stepped in, with America, ready to share nuclear-powered submarine technology. Joe Biden is looking beyond Nato, to a new coalition of the willing prepared to help it in its bid to check Chinese power in Asia. Critics wonder what muscle Britain could possibly add to the US navy, but that is not the point. The US has secured a toughening of the UK’s line on China. And because of the institutional nature of this three-way alliance, it can be confident that Britain won’t change its mind and try to court favor with Beijing again.

‘The relationship has foundations deep enough that it can survive whatever political winds are blowing,’ says one British source. This is vital. It means that the pact doesn’t depend on any personal chemistry between leaders; that defense and technology cooperation between these three countries will now continue regardless of how well the residents of the White House, Downing Street and the Lodge get on.

It’s true that the ‘special relationship’ was particularly effective under Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, but it also survived the tensions between Bill Clinton and John Major and Donald Trump and Theresa May. The AUKUS alliance will stabilize the friendship further. It will be a lasting feature of British foreign policy, and the clearest example yet of what the tilt to the Pacific and the talk of ‘global Britain’ actually means.

Australia sells more to China than its next eight export customers put together, creating an economic dependency that might — in another country — have been accompanied by political fealty. Certainly, China thought deference was owed. It reacted with fury to Australia calling for an independent inquiry into the origins of COVID-19 (it is revealing just how upset Beijing got about this). Tariffs were slapped on Australian goods and bureaucratic obstacles raised to its exports. This was an attempt to bring Canberra into line — and a way of showing others how dangerous it is to question Beijing.

Australia has faced cyber attacks which have all the hallmarks of a Chinese operation. Two Chinese spy ships placed themselves off the Queensland coast to watch the Australian military exercise with its allies. No wonder Australia — surrounded by three oceans — has decided it needs nuclear powered subs, which can travel further than the diesel-fueled ones they had agreed to buy from the French. What started as a defense need morphed into a new military alliance.

The attraction for the US of such a deal was obvious. Washington is currently trying to construct a series of alliances in the Pacific to counter China. For Britain the appeal was that it showed how the UK could be relevant in this part of the world for decades to come. It gave new purpose to the 2007 decision to buy two aircraft carriers and it gave the Royal Navy a mission.

All of this is deeply controversial. ‘If Afghanistan proved anything, it’s that Britain is now a regional rather than a global power,’ says one senior British military source. ‘A political decision to build those aircraft carriers in Gordon Brown’s constituency has ended up shaping our defense alliance — thinly stretched, and of barely any use to the US navy.’ It’s a common view. Wouldn’t it make more sense for Britain, whose defense spending is only 8 percent of America’s, to concentrate on its role in European security?

But the Pacific is where the future is being shaped. The US-China competition is technological as much as it is military. Countries that aren’t involved in the alliance structures of the region will find themselves being left behind technologically. Indeed, an important part of the AUKUS partnership is cooperation on artificial intelligence, quantum computing and cyber warfare. One consequence of this will be that Washington demands restrictions on who buys UK technology companies, with the aim of preventing valuable intellectual property ending up in Chinese hands.

We can expect other groups to form. The so-called Quad — the US, Japan, India and Australia, which started off being used for joint naval exercises — is now working together to build secure semiconductor supply chains.

The AUKUS deal has been met with public enthusiasm in Japan and implicit encouragement in India — suggesting that, in time, there’ll be considerable overlap between these various US alliances. It’s even possible that AUKUS could be expanded. The most likely country to be added to the pact would be Canada. Like the founding members, it is also part of the Five Eyes intelligence grouping, making cooperation on fundamental state business a comfortable fit. New Zealand, however, won’t be joining: it doesn’t allow nuclear submarines to operate in its waters, and Jacinda Ardern takes a very different view on China.

When Boris Johnson first became prime minister few would have had him down as a China hawk. At the start of last year he was considering giving Huawei the contracts for building the UK’s 5G network (such deals are still in place in much of Europe). Even earlier this year he was complaining to friends about what he saw as excessive anti-China fervor amongst certain Tory backbenchers. Johnson, foreign secretary at the time of the Salisbury poisoning and who describes his attempt to reset relations with Russia as his biggest mistake, was happier calling out Moscow than Beijing.

But China’s recent behavior — in particular its treatment of Australia and the clampdown on Hong Kong, which breaches the treaty it signed with Britain ahead of the handover — has seen the Prime Minister taking a much tougher line. It will become tougher still with the arrival of Liz Truss at the Foreign Office. As trade secretary she did little to hide her views on the need for the West to respond to China’s abuse of World Trade Organization rules.

AUKUS has its advantages, but there are also risks, the biggest coming not from China’s strength but its weakness. The AUKUS submarines will take years to arrive and the danger is that Beijing tries to get ahead of the new alliances emerging in the Pacific, and tries its hand now, perhaps tightening its control over the waters around Taiwan. In a decade’s time, the US-led world order will be better placed to check China. The worry is what happens between now and then.

The influential American strategists Hal Brands and Michael Beckley have pointed out that — like Wilhelmine Germany or Imperial Japan in the 1940s — China might conclude that its rise is slowing, and that, if it doesn’t act now, then its moment of opportunity will have passed. This is what makes the next few years so dangerous.

The recently-retired head of US Indo-Pacific command warned Congress before he left the service that China could try to seize Taiwan within the next six years.

China’s rate of economic growth has halved since 2007. It is increasingly saddled with national debt — now an astonishing 280 percent of GDP, far more than any European country. China has been a middle-income country now for a quarter of a century, and is still pretty far from graduating to a high-income country. None of the countries that avoided the middle-income trap in the second half of the 20th century — South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore — spent three decades as a middle-income country. President Xi’s actions in recent weeks — banning private tutoring, reining in Chinese tech companies and squeezing the property sector — will all hit foreign investment, which has done so much to spur Chinese growth.

We’re used to bemoaning the West’s demographic problems, but China’s are particularly serious. The one-child policy went on for so long that China’s working-age population is already shrinking. Unless there are sudden and drastic improvements in labor productivity, a smaller workforce will mean slower economic growth — alongside an aging society. By 2050, a third of China’s population will be aged over 60.

Beijing’s belligerence is compounding the problems. Its ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’ drove Australia into this new alliance and will see other countries join balancing coalitions. Japan’s decision to move away from its 1 percent of GDP cap on defense spending is a result of Beijing’s attempt to turn the seas around it into Chinese lakes. China’s idiotic border skirmish with India in the Himalayas has pushed New Delhi to seek more cooperation with Washington. India was non-aligned in the first Cold War; it won’t be in the second one. China would have done far better strategically to continue biding its time, hiding its capabilities and deepening other countries’ economic dependence on it.

There are few issues of bipartisan agreement in American politics these days, but the need to counter China is one of them. We can, therefore, expect this US alliance building to become as central to US foreign policy as countering the Soviet threat was during the Cold War.

Washington is deliberately ambiguous on whether it would defend Taiwan from attack. But in reality, no US president would have a choice. Revealingly, Biden recently said that the US had a treaty obligation to protect Taiwan — even though it does not. To allow China to seize Taiwan would mark the end of the US-led world order.

Emmanuel Macron is in no doubt about what AUKUS means. His fury is not just commercial pique. The French want Europe to have ‘strategic autonomy’ and for the EU to have its own strategy for navigating the US-China competition. Britain and Australia recognize that countering China will require American leadership, just as taking on the Soviet Union did.

Support for the US and our other allies in the Pacific as we try to check China will now be one of the defining features of British foreign policy. The AUKUS deal will be followed by greater Anglo-Japanese cooperation on the future combat air system. Britain’s alliances are being deepened by this technology sharing, giving this country a relevance in the Pacific that it has not had for decades.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.