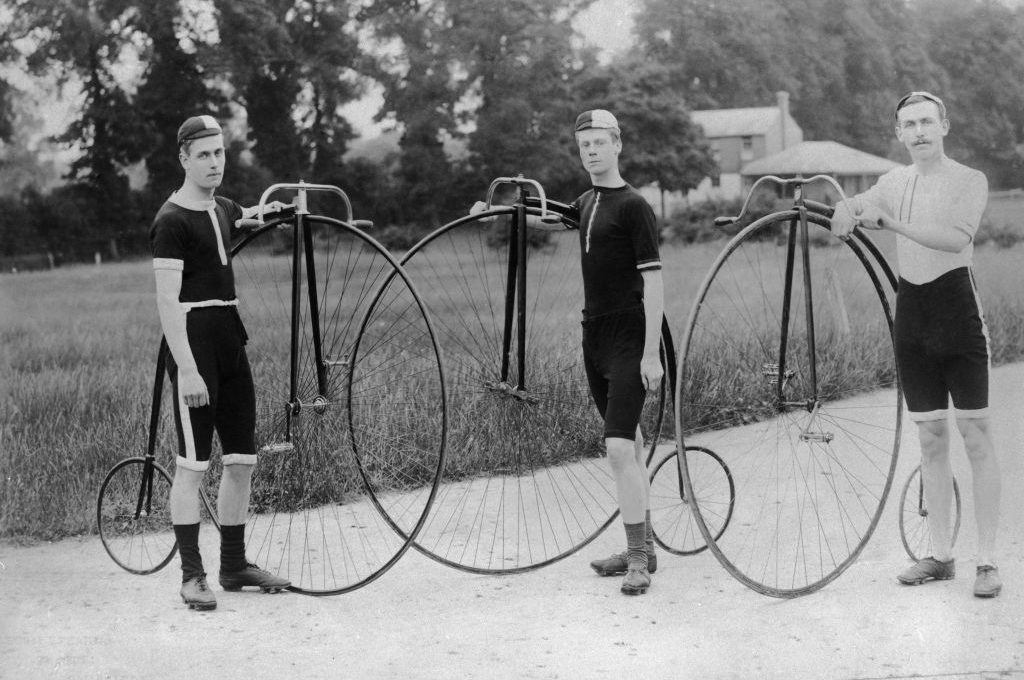

Jill Lepore reviews three new books on the bicycle in the New Yorker. I know this because she mentions the titles in between long passages about the first bike she learned to ride, how many bikes she has owned, and how many times she’s been hit by a car. She also tells us that bicycles are machines of the left, though for some reason this hasn’t stopped them from being used in the service of war and colonialism:

Bicycles and bicyclists veer to the political left. Environmentalists ride bicycles. American suffragists rode bicycles. So did English socialists, who called the bicycle “the people’s nag.” Animal-welfare activists, who opposed the whipping of horses, favored bicycles… But bicycles have also been used in warfare on six continents, and were favored by colonial officials during the age of empire. After the League of American Wheelmen started the Good Roads Movement, in 1880, the asphalt that paved the roads for bicyclists was mined in Trinidad, and the rubber for tires came from the Belgian Congo and the Amazon basin.

You get the idea. She tells some of the history of bicycles, but she mostly complains that America would be a better place if it weren’t so beholden to the automobile lobby that has forced governments to design cities exclusively for cars, as if Americans wouldn’t be buying Mustangs and Teslas today were it not for the political machinations of Buick.

Listen, I’m a big cyclist, and I wish there were better roads for cyclists and drivers were better about respecting the space of cyclists on the road, but the simple opposition between the bike and the automobile that Lepore makes in the review is just that — simple — and is refuted by one of the books she is ostensibly reviewing.

One of Jody Rosen’s main points in Two Wheels Good: The History and Mystery of the Bicycle is that the history of the bicycle and cycling is complicated —“real things in the real world” often are, he writes. He notes, for example, that we have the roads we have today largely beca use of “the Good Roads Movement,” which was a “political crusade led by cyclists.” The first “car” Henry Ford developed wasn’t a car, it was a bicycle with four wheels. “Parts essential to the development of cars,” he continues, “from ball bearings to break pads, were first developed for bicycles. Cornerstones of the automotive industry — the assembly lines, dealer networks, planned obsolescence — were likewise pioneered by bicycle magnates, many of whom transition from bikes to the car trade.”

You can pit the bike against the car all you want, but we have the car because we have bikes.

In other news

Inigo Philbrick gets seven years for fraud: “A US District Court judge today sentenced the disgraced art dealer to serve seven years behind bars for crimes connected to his now-collapsed art-dealing business.”

Christopher Alexander, the architectural populist: “The architect, who died in March at eighty-five, denounced his profession’s establishment and championed the intuitions of amateurs. In a famous 1982 debate at Harvard, he accused the deconstructive architect Peter Eisenman of ‘f—ing up the world.’”

Andrew Ferguson reviews a new book on 1960s Hollywood: “Don’t worry, all you young bookworms out there! Before too long the baby boomers will be dead and you won’t have to worry ever again about anybody asking you to read books like Mark Rozzo’s Everybody Thought We Were Crazy: Dennis Hopper, Brooke Hayward and 1960s Los Angeles. The book chronicles the early lives and marriage of the subtitled characters: Hopper, a second-tier movie actor soon to become famous for directing the hippie hymn Easy Rider (1969) before plunging into drug-drenched obscurity, only to rise again as a weirdly intense character actor in movies like Blue Velvet; and Hayward, by far the saner partner, a daughter of Old Hollywood and, after her divorce from Hopper, a famous Manhattan socialite and fashion plate of the 1970s.”

Ignore the improper use of “begs the question” in this piece. Read what Guillermo del Toro has to say about the state of film today.

Lost Amazonian cities are discovered from the sky: “Mapping technology cut through the canopy to detect sprawling urban structures in Bolivia that suggest sophisticated cultures once existed.”

Joseph Epstein didn’t care for Geoff Dyer’s The Last Days of Roger Federer (linked in a previous Prufrock). Alex Perez thinks it is a “marvel”: “Dyer’s book, part memoir and part examination of the discombobulation induced by diminishing genius, is a marvel due to his encyclopedic knowledge of his heroes and an ability to frame himself as an understander of genius while not quite being one himself. On the other side of middle age, he harbors nothing but admiration for those men who reached artistic heights he could only dream of. Dyer is no longer a young man trying to dethrone his heroes but a pleased ambassador for their greatness, which makes him a perfect guide for a journey on the diminution of said greatness.” Read the whole review in the June edition of The Spectator World.

Why are historians upset at the New York Times for their reporting on the economic development of Haiti? Jack Shafer explains.

Roger Angell has died. He was 101.

Alexander Larman on the Ricky Gervais controversy and Netflix’s response: “Netflix seems to have doubled down on the idea that Gervais can do what he likes, and they don’t need to offer any apologies or explanation for his actions or their involvement. Instead, they soak up the controversy and watch as SuperNature inevitably become the most watched show on the platform.”