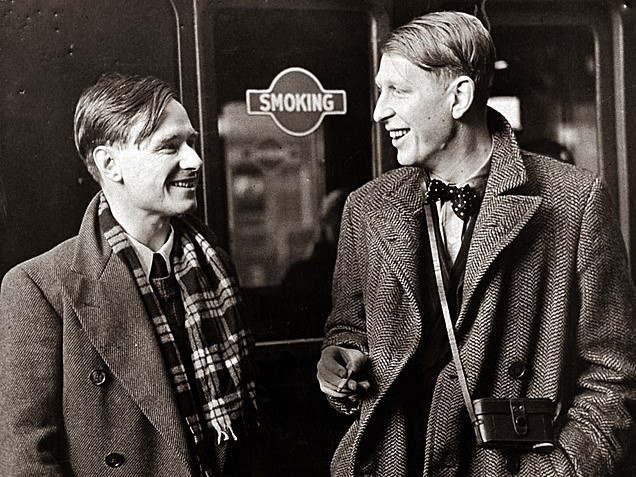

When W.H. Auden was in his twenties, Alan Jacobs writes in a review of the poet’s two-volume Complete Works at Harper’s, he was worshiped by Britain’s intellectual class:

One evening in August 1933, after hearing some new poetry read aloud, the British diplomat and politician Harold Nicolson opened his diary and made a confession: “A man like Auden with his fierce repudiation of half-way houses and his gentle integrity makes one feel terribly discontented with one’s own smug successfulness. I go to bed feeling terribly Edwardian and back-number, and yet, thank God, delighted that people like Wystan Auden should actually exist.” The poet whose reading excited this envy and admiration was twenty-six years old. The adjective “Audenesque” was already in use, and people would soon speak (both reverently and critically) of “the Auden generation” and “the Auden age.” The awe that his verse and presence inspired could rise to a comic pitch; in the same year that Nicolson confided gratitude to his diary, Charles Madge wrote a poem containing these memorable lines: “But there waited for me in the summer morning, / Auden, fiercely. I read, shuddered and knew.”

That changed suddenly when he left England for the United States in 1939 and, shortly afterwards, returned to the Anglicanism of his childhood. This also led, or so it seemed, to a change in his poetry:

The young Auden enchanted and disenchanted, wove some beautiful images while dispelling others. He assumed a role of great power, but when he crossed the sea to his new land and new life, he set all such practices aside. Not long after moving to the United States he wrote an ambitious long poem featuring characters from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, among them Prospero, the great wizard who at the end of that play breaks his staff and drowns his book: “This rough magic / I here abjure.” Auden has Prospero tell his spirit-servant Ariel that he “knows now what magic is;—the power to enchant / That comes from disillusion.”

But, as the Complete Poems show, Jacobs writes, his poetry may not have changed “quite as completely as his contemporaries thought” or “as he himself thought.”

In other news

Oxford between the wars:

“Oxford I do not enjoy,” wrote T.S. Eliot to Conrad Aiken in February 1915. “The food and the climate are execrable, I suffer indigestion, constipation, and colds constantly.” The poet was clearly having one of his bad days. Since arriving at the university the previous October, he had found himself in and out of love with the place, which was hardly surprising, given the timing. Most of the undergraduates at Oxford had either left or were on the verge of leaving to fight for their country, meaning that the lecture and tutorial rooms were almost empty, the sports fields green through lack of use, and the centuries-old traditions stalling like motor cars on the long stretch of the High. The outbreak of the First World War left Eliot marooned in what one of his peers described as “no more than a shrunken skeleton of a university.”

A history of dueling in Europe and America:

The United States regarded itself from its inception as a classless society, unlike the effete societies of Europe, but there were exceptions when it came to the duel. Rank was a problem in a notorious duel in 1838, where the two protagonists were both congressmen. (Joanne B. Freeman in Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic identified seventy encounters involving one or two serving congressmen). Jonathan Cilley of Maine launched an attack in the House of Representatives on Colonel James Watson Webb, editor of the Whig Morning Courier and New York Enquirer, alleging that the newspaper took a soft editorial line on corruption. The dishonored Webb reacted in the expected way with a challenge, which Cilley refused to accept since a mere editor was beneath a gentleman’s notice. Webb then prevailed on Congressman William Jordan Graves of Kentucky to act as his second and deliver the challenge on his behalf, but Cilley again declined. The affair took a new twist when Graves decided that he himself had been offended by Cilley’s manner and issued a challenge on his own behalf. Cilley was obliged to accept. Rifles, another American innovation, were the chosen weapons, and Cilley was shot dead, leaving a wife and three children. Graves was punished by a motion of censure in the House.

Alan Lee on illustrating The Lord of the Rings: “My main concern is to try to avoid providing an interpretation of the story which interferes with the pictures that the author is creating; with such rich material there is a temptation to overelaborate and over-design, so it is important to continually check the text — and those vital maps. I find that watercolor is an ally in my slightly reticent approach to illustration. There is a shifting, unsettled and pro-visional quality in this transparent medium — closer to drawing than painting — which allows the viewer more room to complete the images in their own mind.”

A walk through Vienna with Heimito von Doderer:

Outside Austria, Heimito von Doderer is something of a cult author. His reputation rests mainly on two massive novels, Die Strudlhofstiege (1951; The Strudlhof Steps) and its even longer successor, Die Dämonen (1956; The Demons, 1961). The latter is already available in an English translation by Richard and Clara Winston, but Vincent Kling is the first to attempt an English version of its prequel — a task to which he must have dedicated years of his life… This is often called a quintessentially Viennese novel, although the action is largely confined to a single district of the city, with excursions to the leafy suburb of Döbling and a country house in the Alpine foothills. (Characters also travel to Oslo, Constantinople and Buenos Aires, but we spend little time there.) Part of the spellbinding charm the book exerts on Doderer’s devotees lies in his evocations of atmosphere, often in short lyrical passages.

Marcel Theroux reviews Emily St John Mandel’s Sea of Tranquility: “An interest in complex patterns animates Mandel’s new novel, Sea of Tranquility, though, as in Station Eleven, the naturalism and specificity of its opening gives little idea of the strangeness to come.”

Joe Kahn is the new executive editor of the New York Times: “The Times has a long, sordid history of doing what it has to do not only to survive but to stay top dog. Today, the paper sees its future in China — or, more specifically, in its 1.4 billion news consumers. It launched a Chinese edition of the paper and a luxury lifestyle magazine geared towards the country’s leisure class. And it will pursue this goal no matter what the cost, including by toeing the line on issues sensitive to the CCP. With the hiring of Kahn, the former China correspondent, the pull here is obvious.”