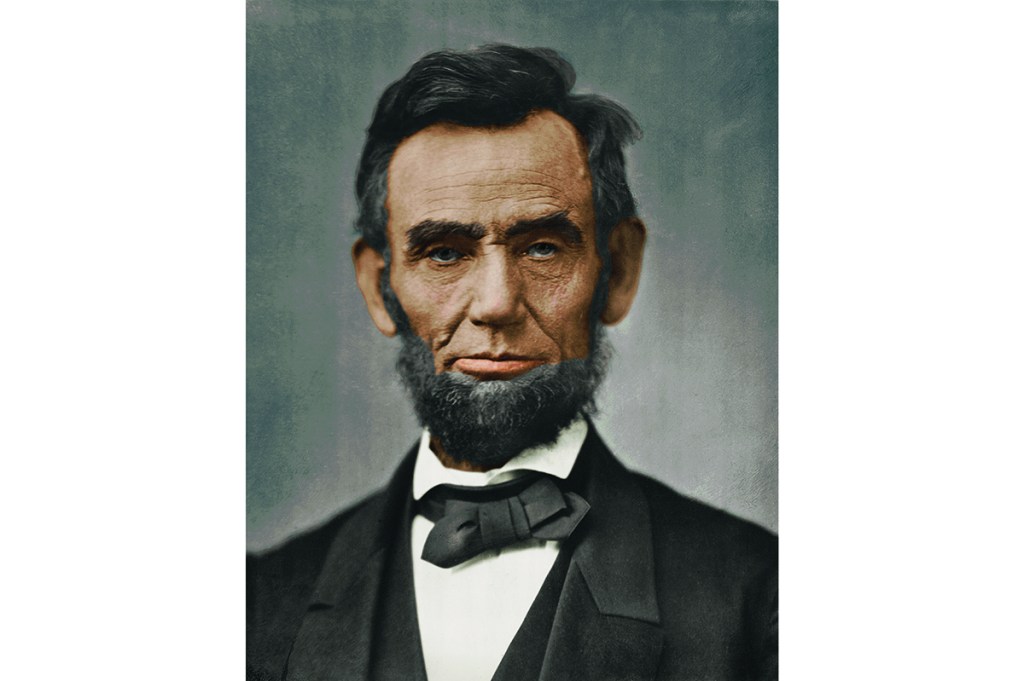

I hope Abraham Lincoln rests in peace. He got little of it as president. What solace he did find often came during stays in what today is known as President Lincoln’s Cottage, a thirty-four-room Gothic Revival home three miles north of the White House. This little-known site is where he, his wife Mary and son Tad lived for thirteen months during summers and falls from 1862 to 1864 — key periods when he wrote the Emancipation Proclamation, when the Battle of Gettysburg was fought, and when he was struggling to win reelection.

Lincoln escaped to this 300-acre hideaway, the former home of a banker set on a wooded breezy plateau, to flee the heat — and the White House. His son Willie had died there of typhoid at just eleven, shortly before his first stay.

Solace was hard to come by, especially for someone with a melancholy soul. Next door Lincoln saw veterans on peg legs thumping paths at the Military Asylum, the nation’s first disabled soldiers’ home. Facing his home — the ultimate reminder of the war—was America’s first national cemetery. Lincoln heard “Taps” played almost daily.

Many nights the gloomy president entertained friends with recitations from Shakespeare. He loved this morbid soliloquy from Richard II: “For God’s sake, let us sit up on the ground/ And tell sad stories of the death of kings:/ How some have been deposed; some slain in war/ All murdered.”

Beyond the gates, military traffic rattled past. Lincoln heard rifle shots from skirmishes near and far. When Confederates attacked nearby Fort Stevens, Lincoln went there twice, the second time with Mary. While he was standing on the parapet, a sniper shot a doctor next to him.

On one occasion a spooked Lincoln may have skedaddled. One night in August 1864, the private on gate duty claimed — years later — to have heard a rifle shot. A hatless Lincoln galloped up the hill. Curious, the guard found his top hat pierced with a bullet hole. When he returned it to Lincoln, the president said he wanted the story “kept quiet.”

Lincoln resented his military keepers. “I cannot be shut up in an iron cage and guarded,” he griped. Many mornings he rose early and rode alone to work, leaving troopers to scurry after him like Keystone Cops.

The poet Walt Whitman, who was living in Washington, saw the president almost daily as he rode by and noticed his “dark brown face, with deep-cut lines, the eyes, always to me with a deep latent sadness in the expression,” he wrote. “None of the artists or pictures has caught the deep, though subtle and indirect expression of this man’s face. There is something else there. One of the great portrait painters of two or three centuries ago is needed.”

Seeking my own escape, I visited the Cottage the day after Russia invaded Ukraine. Now a national monument and only open to the public since 2008, it gets few visitors: 35,000 a year, a speck compared to the eight million who climb the Lincoln Memorial’s steps.

CEO Michael Atwood Mason says his team is working to up the numbers, but he is tight-lipped on specifics. Mason, who has a soothing touch, tells me: “I worry about the end of the American republic. I worry about the constant erosion of human rights around the world, including here.”

The morning of my visit, a chirpy guide led a tour for a dozen female tourists clad in shredded, tight jeans. The Cottage is left empty to let visitors’ imaginations bubble.

With only pink walls to contemplate, I imagine Tad, who had a cleft palate, lisping “Papa Day” instead of “Dear” to his long-suffering father. Mary lights into secretary of war Edwin Stanton. He jokes that a painting should be commissioned of her on Fort Stevens’s ramparts. “I can assure you of one thing, Mr. Secretary,” snaps mad Mary. “If I had had a few ladies with me the Rebels would not have been permitted to get away as they did!”

In October 1864, a British tourist, George Borrett, drags Lincoln out of bed. “There entered through the folding doors the long, lanky, lathe-like figure… with hair ruffled, and eyes very sleepy, and — hear it, ye votaries of court etiquette! — feet enveloped in carpet slippers,” Borrett wrote.

I am agog at the thought of Lincoln attending séances Mary held to reach dead Willie.

Outside, the chill ends my reverie. The grounds are deserted, except for ducks on a lawn overlooking the distant Capitol dome that pops out of a blanket of mist. I follow a path set by the Cottage’s podcast tour. The narrator’s narcotic voice reminds me that I tread the traditional territory of the Nacotchtanks. Beside an ancient tree, she whispers, “If you feel moved, you’re welcome to embrace the tree in a hug.”

At noon a carillon in the Military Asylum’s tower rings out “Anchors Aweigh,” “As the Cassions Go Rolling Along” and “Off We Go Into the Wild Blue Yonder”. The bright bells give each a weird cheery feel.

Today 300 retired enlisted men live here in an Armed Forces Retirement Home. Six years ago, Prince Charles visited. He rolled a bowling ball down the Home’s small alley and toppled two pins. “Big cheer went up. Cameras clicked madly,” USA Today reported.

Lincoln had quieter amusements. He played checkers on the back porch with Tad.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.