Some 35 years ago I visited the National Gallery of Sicily in Palermo on the hunt for the ‘Virgin Annunciate’ by Antonello da Messina, the painter of the beautiful ‘St Jerome in his Study’ in the National Gallery in London. It was hard enough to persuade anyone that the gallery was meant to be open, and what staff there seemed to be about (a couple of deeply suspicious museum guards) had clearly dedicated their lives to saving the gallery’s electricity, rationing us in a succession of deserted rooms to a few seconds in front of any one painting, before plunging the room into darkness, and hustling us into the next.

Museum guards in Siena must be made of more pliant stuff, because Hisham Matar was able to enjoy his month in the city at a very different pace. As a student of architecture in London in the 1990s he had become a frequent visitor to the National Gallery, and 25 years later an obsession with Sienese painting, that began with hours spent in front of Duccio’s ‘The Healing of the Man Born Blind’, finally brought him to Siena, to a flat in an old palazzo and his own folding chair, courtesy of the Pinacoteca staff, to gaze for as long as he liked on his favorite school of paintings.

Fifteen short chapters of this slender memoir take us from Duccio, to Siena the city, to Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s allegories of good and bad government, to Caravaggio and Poussin, to a chance meeting with a Jordanian, a walk in a cemetery, the Black Death and back to Lorenzetti and his ‘Madonna del latte’. These external stimuli give rise to a fluid series of meditations on big questions of life, on love, faith, time and on the nature and purpose of art, the influence of architecture and, most important of all to this author, grief, mourning and memory.

Matar’s books to date all deal to some degree with the loss of his father, a Libyan diplomat turned dissident who fled the Gaddafi regime but was kidnapped in Cairo, returned to Libya, imprisoned and disappeared. Matar’s two novels spring from these events, and his Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir, The Return, movingly chronicles his dogged determination to discover his father’s fate. Matar’s month in Siena came shortly after The Return was finished, and his memories of it are framed and shot through with the same passionate, sad keynote. It was during his London student years, the Duccio time, that his father was seized, and it is his father, an ever-present absence, who lies behind the most telling passages here.

One is Matar’s chance playing, on the random shuffle on his phone, of his wife’s address to the father-in-law she never met, but who she conjures up, as though she knew him intimately:

‘I imagine you light and agile, placing your keys by the door, greeting the maid with respect. I imagine men pausing in conversation, waiting for you to speak, and your wife making sure things are the way you prefer, your salads well seasoned and fresh, your shirts ironed, your papers left undisturbed.’

For Matar himself, the Siena experience marked a more final stage in his mourning. It came, he says:

‘…at a resonant juncture: the time between having completed a book and seeing it made public; but also at that strange meeting point of two contradictory events — the bright achievement of having finished a book and the dark maturation of the likelihood, inescapable now, that I will have to live the rest of my days without ever knowing what happened to my father, how or when he died or where his remains may be.’

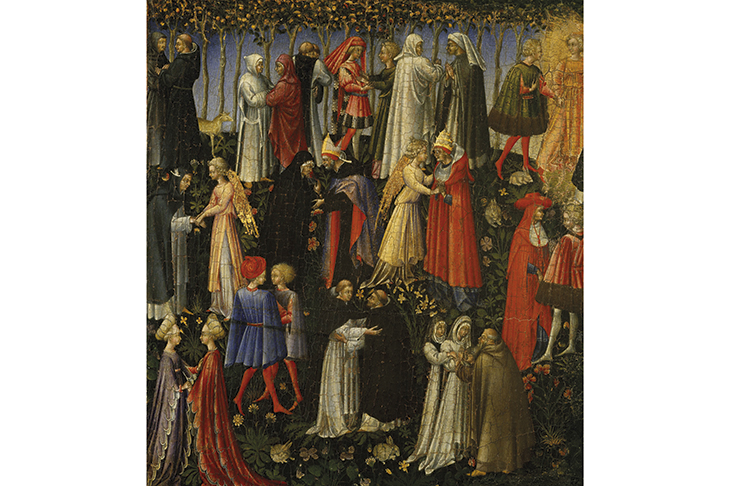

After the hope beyond hope of The Return, that somehow his father might still be alive, this is a sobering moment, and would have been a dark finish to this little, essentially life-affirming, book. So how splendid that its conclusion whisks the reader away from Siena, though not away from the Sienese School, to Giovanni di Paolo’s ‘Paradise’ in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This paradise is the paradise of reunion, and in this painting, at last perhaps, Matar has found a new way to think about his great loss. ‘What is it,’ he ponders, ‘for the dead to remember the living… to still be able to recognize those we knew when the soul was flesh?’ In this encounter in the hereafter, where all that has happened since the last meeting is explained, lies for Matar the ultimate consolation:

‘The painting understands this. It knows that what we wish for most, even more than paradise, is to be recognized; that regardless of how transformed and transfigured we might be by the passage, something of us might sustain and remain perceptible to those we have spent so long loving.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.