‘I’m going to be linked with him until I die,’ said Luke Perry of Dylan McKay, the character Perry played in Beverly Hills 90210. He was right. On Monday, Perry tested his theory to its conclusion by dying aged 52, following a massive stroke.

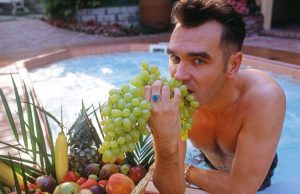

To late Gen X-ers now in our early forties, Perry is forever pickled in the aspic of 1990. Dylan McKay was a Diet Coke-swilling, James Dean for the MTV generation. In the very first episode of Beverly Hills 90210, he rode into the zip code of the stars and their servants astride a motorbike, wearing an unseasonably warm leather jacket and an oiled quiff that gleamed in the California sun. And there he stayed, at least in our imaginations.

Beverly Hills 90210 found low ratings and poor reviews on initial transmission in October 1990. But it crept up on an unsuspecting viewing public like O.J. Simpson, and finally became so popular on both sides of the Pond that producer Aaron Spelling’s wife Candy could get herself a whole new Present Wrapping Room. Perry’s character seemed old-fashioned even then, an idea of 1950s Americana whose white T-shirts and biker boots had been hastily reheated along with Nick Kamen’s wet Levis. Here he was, girls, the smoothly-coiffed, drawling sex-person that was Luke Perry.

While our hearts throbbed obediently, Perry’s character Dylan McKay faced a terrifying challenge, dating Shannen Doherty’s character, Brenda Walsh. Dylan and Brenda eventually achieved copulation, much to the viewers’ excitement and the concern of parents who forced the network to add an unscripted pregnancy scare. Perry’s style, as Brenda could attest, was seductive and lackadaisical, underpinned with a husky voice that suggested a midget Brando lurked within. He did most of his acting with his left eyebrow, whose sexy and highly articulate scar showed that Dylan McKay had lived.

The other eyebrow actor from whose chiseled cheekbones Beverly Hills 90210 was suspended was Perry’s co-star and fellow heart-throbber, Jason Priestley. The show ran for 10 seasons, and made stars of its actors. Somehow, these tidy and somewhat emasculated youths seemed to possess otherworldly glamour. But the minds and hearts of young girls are fickle things. No one wants to see the high-school heartthrob once he’s graduated from the college of life with only a passing grade. We grew up, the world turned, and Perry was forgotten, even when a much younger generation got to know him as the dad in Riverdale.

Only America could have produced the wide, Ohioan vowels of Coy Luther ‘Luke’ Perry III. Only Essex could have produced the Mohawk-crowned raver turned gentle publican Keith Charles Flint. He died on the same day as Perry, aged 49. If Perry was the image of my adolescence, Flint’s band, The Prodigy, provided the rave soundtrack to a million Gen X-ers who pilled and partied through the dance clubs of Britain in the early 1990s. We loved him, despite the fact that most of his lyrics were unintelligible, and that he didn’t write the songs. The ‘prodigy’ of the band’s name was Liam Howlett, who has attributed Flint’s death to suicide.

The Prodigy’s biggest hit, Firestarter (1996) established the band as the ‘Godfathers of Rave’, and broke into the US market. Flint wore a studded leather dog collar and garishly gothic make-up, and he finished the look with a spiked Mohican which looked permanently surprised to see us. He described himself as self-destructive, and was open about his drug use. ‘I got bang into coke, weed, drinking a lot,’ he told the London Times in 2009. ‘This made me reclusive, boring and shallow. I’d line up rows of pills and just take them and take them, and I’d lose track of how many until I passed out.’ But his bark was worse than his bite. The hedonistic, twisted firestarter who was the twisted face and screaming voice of wailing, thumping, head-banging floor-fillers, ended up buying a small country pub outside London.

Flint, no stranger to bizarre costumes, bought a horse and rode with the hounds of the local hunt. When he added logs to the old pub’s open fire, any patron who quipped, ‘Firestarter!’ was promptly told to put a pound into the charity box. But Flint seemed unable to escape the persona whose manic rendering of Prodigy ditties like ‘Smack My Bitch Up’ had caused the BBC to ban its video.

Similarly, Luke Perry spent a couple of decades in an early-Nineties time machine. While Jason Priestley was seriously injured in 2002 by driving his race car into a brick wall in Kentucky, Perry recently learnt that he had cancer of the colon. Meanwhile, the tales of on-set physical spats which shaped Shannen Doherty’s 1990s career have been followed by tales of Doherty having more on-set physical spats in the 2010s, all the while failing to draw a line between her private and public life. Their audiences had outgrown them, but they could not outgrow their personae.

Nothing that Flint or Perry could do would ever eclipse their Nineties’ output. Nothing could restore them to eminence in the minds of the once-young who had watched them or danced to them. They were untranslatable, unable to shift from one era to another. Which was strange at first, but is now familiar.

It’s impossible for Generation X’s television and rave icons to acquire anything like the longevity of the Sixties’ rock stars, or even Eighties’ stadium-fillers like Jon Bon Jovi. Fame used to be forever, but Perry and Flint became famous just as the culture was beginning its digital acceleration. The genres have collapsed like a wet Mohican. Long after everyone else has got their coats and gone home, images from thirty years ago fill our screens, showing a television star locked in the past, and a techno raver stuck inside a nightclub, forever.