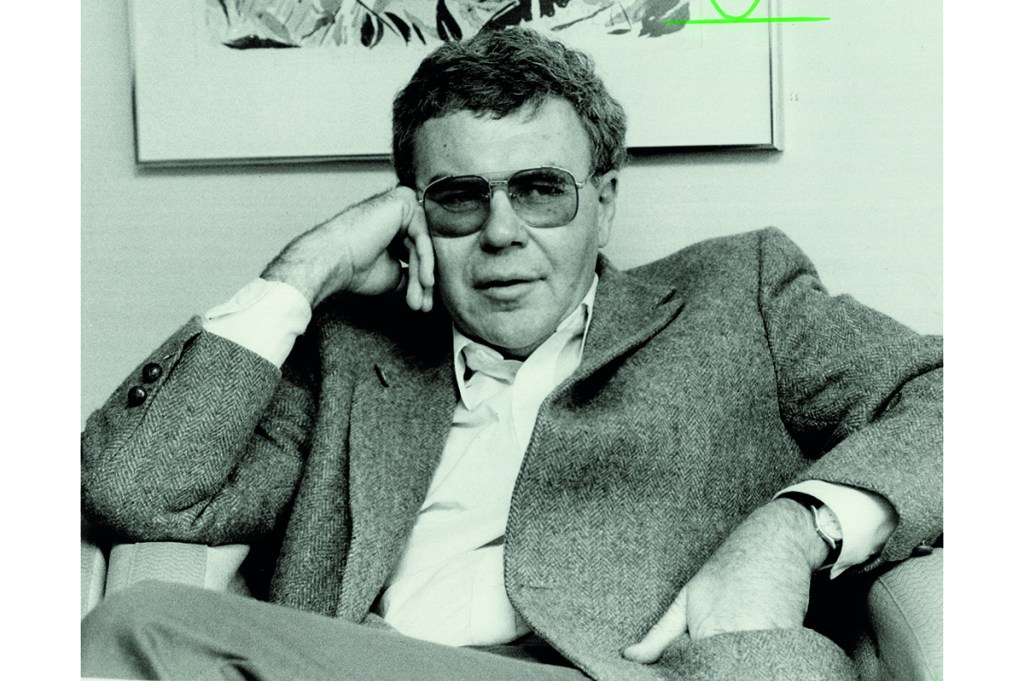

I recently finished yet another predictable novel about Brooklyn neurotics and needed a gritty palate cleanser. Raymond Carver’s Where I’m Calling From: Selected Stories seemed ideal. Carver, a master of the short-story form, has long been one of my go-to writers, but, in recent years, he has increasingly lost literary relevance. Twenty years ago, Carver’s terse, minimalistic style was all the rage. Like Hemingway and Bukowski, Carver birthed a sea of mediocre imitators onto the American literary scene. In most US short-story collections published in the Eighties or Nineties, Carver’s stylistic and thematic influence is evident from the first page. But as Carver’s aesthetic sensibility of blue-collar masculinity has been excised from elite culture, books like Where I’m Calling From are only read by literary aesthetes in mourning for the American short story.

Carver was the king of my favorite literary sub-genre: dirty realism. The term itself was coined in 1983 by the British literary magazine editor Bill Buford. He defined the term in the introduction of Granta 8: Dirty Realism:

A new fiction seems to be emerging from America, and it is a fiction of a peculiar and haunting kind. It is not only unlike anything currently written in Britain, but it is also remarkably unlike what American fiction is usually understood to be. It is not heroic or grand: the epic ambitions of Norman Mailer or Saul Bellow seem, in contrast, inflated, strange, even false… It is not a fiction devoted to making the large historical statement… This is a curious, dirty realism about the belly-side of contemporary American life.

As a young writer from a working-class background, Carver and other dirty realists such as Mississippi-born Richard Ford and Larry Brown opened my eyes to a fictional terrain populated by the sort of non-literary characters that resembled my Cuban-American Miami neighborhood. Up until then, I considered the literary life, and literature in general, a rarefied realm designated for highfalutin elites with their tales of traversing the Upper East Side and other fancy environs. It was inconceivable to me that anyone would want to read about my shady immigrant cousins who hung out at the strip joint or my neighbor who ran a cockfighting ring out of his garage. But then I read stories by the dirty realists that took place in seedy diners and bingo halls; they featured the least “literary” characters I’d ever met. Garbage men, sad divorcées, bus drivers and insecure jocks — the entire gamut of American failure and dysfunction, apparently, was worthy of literary representation. So I started writing about the forgotten, everyday losers that I’d taken for granted.

The beauty of dirty realism is that it captures regular life in all its stupefying, and sometimes transcendent, malaise. What connects most people, and sends them to bars, sporting events and other communal spaces, is the existential loneliness that can only be assuaged by connecting, if only fleetingly, with your fellow lonesome travelers. The dirty realists understood that this loneliness is the true equalizer and if literature is to speak to the great truths of the human condition and heart, it begins there.

Dirty realists examine the loneliness at the center of things with greater clarity than other writers because the genre necessarily eschews pretension. It highlights characters who face the degrading human tasks at hand without resorting to affectation or self-deceptive intellectualization. In that sense, dirty realism is the antithesis of the current ascendant literary genre, autofiction, which prizes cloying cleverness and smug irony over traditional modes of characterization and truth-seeking.

The form is successful at mining the human experience because, as Buford noted, “it is not fiction devoted to making the large statement,” unlike contemporary fiction, which is mostly about the sociopolitical obsessions of elite progressives. An example of this concern with the “large statement” is Alexandra Kleeman’s critically acclaimed Something New Under the Sun, a dystopian novel that takes place in a future California decimated by climate change. Kleeman’s novel is just one of many that traffics in woke political content that is strictly engineered to please progressive-minded readers. These novels, whether about climate catastrophe or systemic racism, now make up the bulk of what is published by New York presses and have defeated the chance of a dirty realism revival.

The irony is that the “large statement” novels cater to a small, elite audience, while a working-class genre concerned with, as Faulkner called them, “the old verities” would have far more universal appeal. Dirty realism, like much American literature, was mostly written by white men, but more important than the supposed “whiteness” of its authors was the way that their work transcended race and class, which is how a Cuban-American kid such as myself was able to connect with Carver and my other favorite, Larry Brown, whose short story collection, Big Bad Love, a masterpiece of Southern despair and redemption, inspired my own first short stories.

Miami or Mississippi; it don’t matter, so long as it’s dirty and realistic.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2022 World edition.