Duncan Hannah, wild child of Andy Warhol’s 1970s, matured to the art world of Eighties New York. The following is an exclusive excerpt from his as-yet-unpublished diaries that chronicle a decade of growing up and getting down — of painting, writing, reading, heroin, AIDS, infatuations, sobriety, Reagan and more.

February 15, 1984: Semaphore Gallery sold the painting “Christmas” that I painted on Christmas.

Hooray!

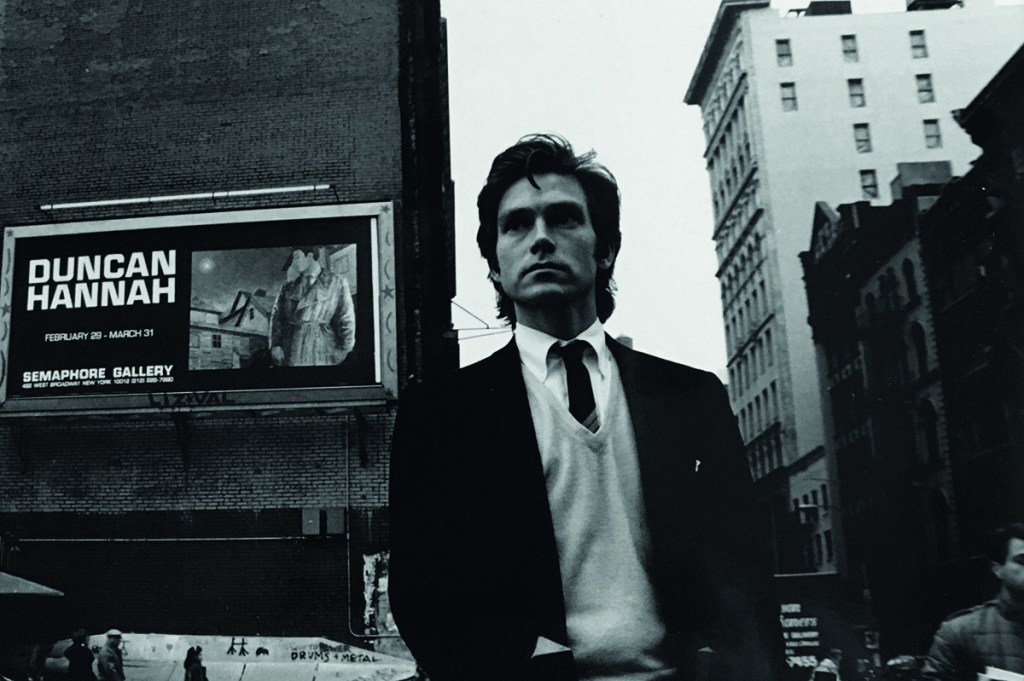

I was in a cab coming down Broadway with Greg Crane and Simon Lane. We stopped for a red light at Houston Street. Crane said “Oh my God, LOOK!” and pointed to the south side of the street. Above the New-Wave fruit-stand, illuminated in the darkness, was a giant billboard advertising my upcoming show at Semaphore. Huge white letters spelled out “DUNCAN HANNAH,” above a color reproduction of my painting of Robert Mitchum in a trench coat, entitled “In the Darkness the Game is Real” (a title lifted from Richard Thompson).

That’s not the only thing that was lifted. Crane said “That’s MY hand!,” and indeed, Mitchum’s right hand was painted by Crane one late night in my studio. Ha! We all basked in the glory of the moment, until the light turned green, and we took a left on Houston to our next stop, Piezo Electric, where I’m in a group show aptly called “Romance & Catastrophe.” The billboard was Barry’s idea: it hadn’t been done before in New York, and he thought it was a Warholian gesture — to use a billboard, normally given to advertising blue-jeans or cigarettes, for fine art. Right at the portals to SoHo, so no one could miss it.

February 29: My show opens tonight, so I balance it with a trip to the Balthus retrospective at the Met. He is currently my main man. I slowly drift through the large exhibition, taking in the vibes. I stand in front of a huge canvas called “The Room,” of a little girl pulling a heavy curtain aside to shed light on a nude pubescent girl stretching like a cat on a mauve velvet chair. So European. So mysterious. So nineteenth century. I open myself to be enveloped by this theatrical scenario. Writer Sanford Schwartz stands behind me taking notes. This show raises the bar for all us contemporary figurative painters. This is a modern master. We’ve got a long way to go. Eric Fischl? Nope. Sandro Chia? Nope. Duncan Hannah? Nope. Balthus has got real resonance.

March 2: John Russell, the New York Times:

Duncan Hannah is a very curious painter. Almost all of his subjects would have been familiar to painters 100 years ago — a woman playing solitaire, some children sleeping off a birthday party, a landscape dominated by a speeding train. But in his handling of them there are echoes of movies — or so it seemed to this visitor — and through them of movie stills. The tension, almost everywhere evident, depends on a back-and-forth pull between subject matter that is delicately dated and a treatment that, though related to a later age, has also begun to have a look of nostalgia. There are exceptions, though. I don’t see Winslow Homer tackling the drunk who stumbles across the street outside a bookstore in one of Hannah’s more unexpected images.

That drunk is me.

May 7: I’m on the wagon again. A new sober friend tells me to contemplate the idea of “change.” He says, “You aren’t changing.” Tells me I was a good power of example when I initially got sober back in 1980, but now I’ve just piddled it away. Just another artist in flames. Old story. He says “It’s easy to handle a crisis, but it’s day to day life that takes real courage. Now that your dreams have come true, it seems to be a nightmare. You have to learn to endure pain, frustration, anxiety, women and money. Stick close to people who are in the same boat and see how they do it. Rise above your destructive urges, instead of succumbing to them.” My benders take the same debauched, chaotic course, and leave me nearly dead. I can lose a whole week. It all unravels. Merely blotto. Stop being an idiotic daredevil. Stop walking a tightrope… there is no net. This adventure is over. I lost the war.

I’ve been painting away like mad, trying to build up my shattered self-respect. Also, Barry [Blinderman] has got a demand for new canvases. I’m visually alert, and making a point to be influenced by my brilliant artistic predecessors. I have to buckle down and invest in my future.

Violet is out with her new friend Julian Lennon, who I met one night. Seems a nice sort of fella. She attracts all manner of celebs.

May 22: de Kooning’s“Women”at the MoMA. “Flesh is the reason oil paint was invented.”

May 26: Glenn O’Brien in Artforum, Summer 1984:

Hannah’s more like the Henry Mancini of the New Wave, or the power-pop Balthus. He makes beautiful paintings that, like beautiful boys and girls, look like they should be popular… Hannah’s large fields of color are not flat, but contain internal abstractions… James McNeill Whistler meets Graham Greene… literate detective mysticism… Puvis de Chavannes meets James M. Cain… there’s a joy in obvious effect, finding a pleasurably hallucinogenic dazzle in an ordinary scene by rewriting its colors… is it Neo-Post-Impressionism?… salvation never looked more like a pretty picture.

Good old Glenn! Of course, HE understands.

May 31: Fairfield Porter retrospective at the Whitney. A revelation! Such an achievement. I study his painterly shorthand treatment of trees, of windows, of faces. I run into Arthur Goldberg, who says the Waspy Southampton idyll depicted was not the whole story, as the poet in the screen porch, schizophrenic Jimmy Schuyler, lived with the Porter family and was Fairfield’s sometime lover, while his wife Anne turned a blind eye to it. Now I can see it. I chat with Tom Wolfe, Carter Ratcliff, Henry Geldzahler.

June 6: House manager Greg Crane lets me in the side door of Carnegie Hall for Frank Sinatra’s sold-out engagement. I sit on the stairs in the balcony. That old black magic is nowhere to be seen. His toupee is too small, his waistline too big. He’s got a monitor with the lyrics streaming by, which he keeps looking down at. For HIS songs! Then that jazzy scat stuff he does, fake ad-libs, like “chicks” and “tomatoes” thrown in like an afterthought… Frank is clearly not into it. His voice is flat. Frank, think back on the nights & days with Ava Gardner! Her loving arms! Put some passion into it! Some oomph! Think about your carnal knowledge of Angie Dickinson! How the sun used to shine between her legs! Of course, all those aged bobbysoxers are wetting their pants over him. It doesn’t matter what he does. He can do no wrong. I wish I hadn’t seen it. I left early.

June 13: “In the End is My Beginning,” group show at Semaphore with me, beautiful Ellen Berkenblit, Walter Robinson, Martin Wong, etc. Title from T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets which I just read, so good, more accessible than I had feared.

I saw Isabelle Adjani on 57th Street today, wearing a big black hat. Lauren Bacall too. Later to a new club in Chelsea, Kamikaze, where I’m in a group show. There’s Bianca Jagger, Lenny Kaye, Jonathan Richman. There’s a bartender everyone seems to know called Bruce Willis who’s very self-assured and funny. Then on to Save the Robots, and finally to Area, where drag artist Ze is in a window tableau portraying Mary Magdalene.

July 9: My sister’s family crashes at my Broadway apartment for one night as we’re all going up to Nantucket. Sage fell asleep with Cicero. As I eat my Rice Krispies in the morning with my niece and nephew, I pick out a cockroach that somehow got in there, flick it to the corner, and continue eating. Their jaws dropped. Shock. Welcome to Bohemia, kids.

November 29: An informal buffet at Flora Biddle’s (granddaughter of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, and current chairman of the board of the museum). Her carriage house (110 East 66th) was remodeled by Michael Graves. She just bought a painting of mine at Patterson Sims’s suggestion. Dora is nervous about this soirée, knowing it will be a stellar crowd. She says her story will be that she’s a dancer, OK? OK.

Flora opens the door graciously, and says “Duncan and Dora, welcome! Let me introduce you around. This is Merce Cunningham and John Cage.” We shook hands hello, and Dora whispered to me, “Forget the dancer story.” Flora led us over to the living room, where she introduced us to Bryan Hunt, Karole Armitage, David Salle and Susan Rothenberg, all contemporaries of mine who are lauded in the Whitney Museum. They were standing in front of my rather large oil called “Mythic Times,” a young man reading a book in front of a windswept coastline, fisherman’s hut, rowboat, etc. It had pride of place on the wall. It was situated between a Cy Twombly and a Jasper Johns, both family friends of the Biddles. There was a lull in the conversation, and Rothenberg glanced over at my canvas and said “Do we know who did this… it’s not Eric, is it?” (The royal “we”). The group looked at my painting in a desultory manner, and shook their heads no. To stop this possibly embarrassing chain of conversation I piped up and said, “I did that.” Rothenberg turned to me with a scowl on her face and said, “Did what?”

“I did that painting.”

“And you are who?” she said, despite the fact that we’d just been introduced by the hostess.

“Duncan Hannah.”

Rothenberg paused, then shook her head negatively as she stared at me, as if to say, “We don’t know you, and we’re not going to know you either.” As if I was an interloper who’d not only crashed the party but crashed this elevated art world. Crashed that bit of wall-space. As if they were the gatekeepers. No one else said a word. Not exactly “Hail fellow well met.” Snubbed. The group dispersed. I proved to be a real conversation stopper.

“Well, THAT was uncomfortable,” said Dora, shocked at the lack of manners.

“Tough crowd,” I replied, thinking of Henny Youngman mopping flop-sweats off his brow. The rest of the evening was better. I reminded John Cage of when we first met. He was digging up dandelions one Saturday morning, outside my old high school. I thought he was a gardener, or a tramp, or a looney. He was in fact an acclaimed modern composer making prepa-rations for dandelion soup for lunch at his hostess’s house (Sue Weil from the Guthrie, where he’d just given a concert, of sorts). He liked this story. Whitney curator Patterson Sims was friendly and said how he loved the way my work mythologized everything. He reminded me that art history was a long, changing road that was continually being revised. “You can never judge the way things will settle in the future from the current fashion of today” he advised.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2022 World edition.