Ennio Morricone’s staff wish it to be known that he does not write soundtracks. ‘Maestro Morricone writes “Film Music” NOT “Sound Tracks”’, explain the printed interview guidelines. ‘Maestro Morricone is a composer. Composers do not use the piano to compose music with, they write their music down directly in musical notes without the interference of any musical instrument.’ Well, that’s Beethoven told. In the classical music world, you hear tales about ‘riders’, the Spinal Tap-like lists of minimum requirements that pop stars issue before consenting to walk among mortal men. You don’t tend to encounter them, though. In the UK, eminent conductors are addressed as ‘Simon’ or ‘Andris’. Morricone? ‘Maestro will do,’ writes his management.

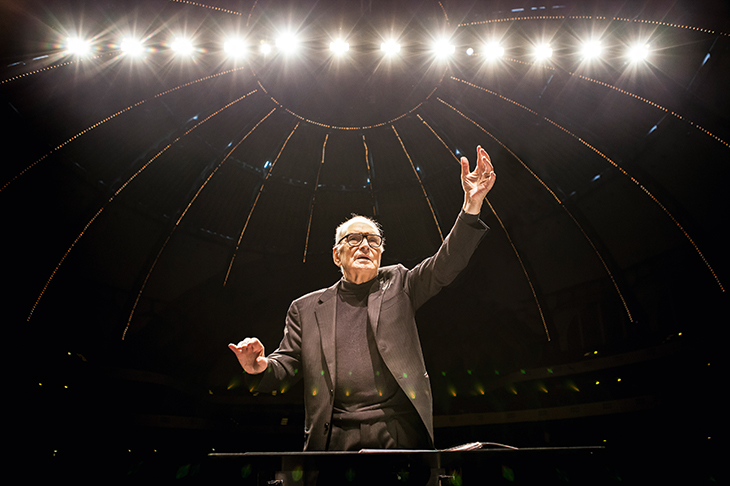

But why pretend otherwise? At 89, Morricone is a pop-cultural phenomenon, whose music for more than 500 films including The Mission, A Fistful of Dollars and Cinema Paradiso props up every movie compilation CD you’ve ever seen discounted at Tesco, and whose 1960s scores for Sergio Leone’s psychological westerns (‘Try to avoid the term “Spaghetti Westerns”,’ caution the guidelines. ‘Italians consider it an insulting description’) remain so influential that merely humming two bars of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is enough to bring an entire genre to dusty, sweaty imaginative life. If his staff treat him like a pop star, it’s because for media purposes he is one.

He didn’t start that way, though. It’s relatively rare now to hear him talk about his studies in the 1940s under the Italian composer Goffredo Petrassi — a serious figure of neoclassical leanings, who taught a flotilla of postwar modernists. That grounding proved fundamental. ‘With Maestro Petrassi, we had to try to compose as they used to do in the past, starting from the year 1100 right up to modern times. And then I went to Darmstadt, the festival in Germany, and really understood what it was to write contemporary music,’ he says.

The name of Darmstadt is significant —the postwar festival where German classical music confronted a compromised tradition and remade itself on ultra-modern terms. Italian music, similarly compromised, made its own swerve towards radicalism. But, ‘Maestro Morricone does not like being reminded of the war’. So let’s just say that by the time he was writing his first scores for his former schoolmate Leone, Morricone was also playing trumpet in the Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza, an avant-garde improvisation collective whose members at one point included the maverick experimentalist Frederic Rzewski. That Morricone still cites Luigi Nono and Aldo Clementi as favourite composers gives you the general drift.

‘Nuova Consonanza really reunited me with the love of my life — composing absolute music, music that is not related to a film, or to a pop song. One of our rules was to avoid anything that was melodic, anything that was usual. We had to produce very strange sounds, very complicated sounds, because we wanted to get as far away as possible from the so-called traditions of classical music. The experience with them really helped me to bear the burden of working in the commercial sector.’

And there’s the central contradiction of Morricone’s career: that a modernist of the most uncompromising seriousness (seek out a recording of his Musica per 11 Violini of 1958 for a palate-scouring taste of his work away from the soundstage) should opt to work in unashamedly commercial cinema, instead of confining himself to social-realist projects such as Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966). And that a composer with such a melodic gift should believe, as a matter of aesthetic principal (it’s all in his book Composing for the Cinema), that ‘in contemporary art music composers do not write themes any more. None of us is interested in making them’. He won’t be drawn on whether his career choices were essentially ideological — a conscious decision to engage with a mass audience, as Kurt Weill did in the 1920s. He has, though, compared the position of cinema in modern culture to that once occupied by opera.

‘I never gave up the idea of concealing radical and contemporary elements, even in my simpler film scores. For instance, sometimes I quoted the name of Bach, or I added just three or four notes from Frescobaldi, or even from Stravinsky — even though the filmgoers or the director would never realise it. It was a kind of moral reward for me. OK, I have to write music that is more easily listened to, because the audience otherwise will not understand. But I still don’t give up completely, and I put in something that is really very satisfying and very rewarding for me.’

It should keep film music PhD students busy, too. The startling fact, as Morricone explains in Composing for the Cinema, is that he constructs his own themes according to rigorous structural and dramatic precepts, sometimes before he has even seen the film. Melodies as spontaneous-sounding as the theme from Cinema Paradiso, or the sky-punching finale of The Untouchables, are fabrications as synthetic, and as carefully assembled, as any post-Schoenberg tone row. Perhaps that’s why Morricone’s music always carries such a powerful sense of itself. The music is almost self-aware: these are movie themes that know they’re movie themes, and Morricone controls every aspect of their presentation. Silences are as potent as sounds and tone-colour, too, is vital — think of the Jew’s-harp and Pan-pipes in the Leone westerns, or the loping, predatory bassoons in Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight. Unlike composers in the Hollywood system, Morricone never delegates his orchestrations to other hands.

‘Being a composer means writing the whole of the music, from the first point till the end, including orchestration. Otherwise, the very last touch of the composition is in the hands of the orchestrator. And so, the music is no longer the music you wanted to write. I am a real composer, and I think that orchestration is an integral part of composition. I mean, if you don’t do your own orchestration, you’re not 100 per cent a composer, in my opinion.’

Well, they said to call him Maestro. What’s beyond question is that Morricone’s career has been underpinned by an artistic seriousness whose ferocity might surprise those who roll their eyes when ‘Gabriel’s Oboe’ tops another Classic FM poll. ‘I can never be passive,’ he says. ‘I like composers who work with honesty, who are very honest in their profession. That’s the kind of composer I admire.’ His O2 concert will be his last in the UK. And perhaps, once the industry circus that surrounds him has found a new cult figure and rolled away, the world of classical music will see that a major post-war modernist has been hiding in plain sight.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.