How did David Mamet spend the pandemic? The answer, as anyone familiar with the prolific, brilliant playwright and screenwriter would probably have guessed, is that he wrote.

“I’ve been writing a lot of essays lately,” Mamet, seventy-four, says when we meet at his Santa Monica home on a cool January evening. “Because, you know, I don’t want to go and sit on a park bench. I’m a writer.” A collection of essays written during the tumultuous plague years is published this month by Broadside, an imprint of HarperCollins. Recessional: The Death of Free Speech and the Cost of a Free Lunch is combative, challenging, witty, and, as the title suggests, its prevailing mood is as dark as the “terrible” period in which it was written.

“Now we are engaged in a prodromal civil war, and American constitutional democracy is the contest’s prize,” writes Mamet. “The universities and the media, always diseased, have progressed from mischief into depravity. Various states are attempting to mandate that their schools teach critical race theory — that is racism — and elected leaders on the coasts have resigned their cities to thuggery and ruin.”

Watching his “beloved American democracy and culture dissolve,” he asked: “What can I do?” He took up his pen. “The question as one ages,” says Mamet in an energetic bass tone, “is ‘What in the world is going on here?’ Especially if you’re a writer and especially if you’re a playwright, because being a playwright is about looking at human folly. It’s not about flogging a horse of your own good opinions or writing marginally good dramas about marginally difficult situations. It’s about saying ‘I just don’t get it.’”

Mamet says he sees life as a tragedy. Informed by his Jewish faith, it’s a view that says: “We’re stuck here in this world of lies… we’re stuck in the world of illusions. What is actually true? I’ve been attacking that piecemeal in the plays and movies I’ve written over the years. We all think we’re doing good and we end up doing evil.”

As you may already have known or, if not, by now deduced, Mamet’s outlook is conservative. Just as the man who brought us Glengarry Glen Ross and Speed-the-Plow is arguably America’s greatest living playwright, he is among the few respected and decorated figures across America’s entire cultural landscape who admit to possessing right-wing opinions.

There are two kinds of liberal apostates: those who claim to be a fixed point in a changed world. It’s not me it’s them, claims this sort. And those who undergo a thoroughgoing conversion. Mamet is the latter. He’s a defector.

His break from the left was decisive. “Why I Am No Longer a ‘Brain-Dead Liberal,’” read the headline of a piece by Mamet in the Village Voice announcing his departure in 2008. That title — not his choice — still annoys Mamet. “It just threw me out of the left,” he says. “I think [the Voice] is gone now. Rest in peace,” he adds with a little relish. Not that the headline really misrepresented Mamet’s position: “I took the liberal view for many decades, but I believe I have changed my mind,” he wrote in the article.

“I didn’t know any conservatives,” says Mamet of his younger self. “You never met a single conservative.” Coming up in theater at his age and living in big cities was to be safely cocooned in a liberal bubble. A place where, he says, bemoaning the right’s latest move was like talking about “terrible weather”: “Did you see what that son of a bitch Nixon, or Reagan, or Thatcher did today?”

And so the conservatism he would grow into was self-taught. “I started reading. I came across The Road to Serfdom,” he says. After Friedrich Hayek came Milton Friedman and Thomas Sowell. (Sowell, a prominent black conservative economist and, like Mamet, a man who started his political journey on the left, is the person cited more than any other during our conversation.) “My reading got broader and broader and I thought, I’ve got to take this down to the bare paint.” Next came Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, Tom Paine and the Founding Fathers. Out of that came a realization of the “extraordinary brilliance of the American experience.”

About the impact of politics on the theater, he is clear: “The problem is writing plays about good topics. People can write plays about good topics — that black people have been oppressed, gays have been oppressed, black people are good, gays are good. They’re all true. They just aren’t very interesting.” Mamet approaches his craft with a customer-is-always-right humility. He says that playwrights can only get better if their work “appears in front of an audience where failure can’t be appealed. If failure can be appealed — ‘Wait a second, you don’t like my play about Native Americans?’ — then it’s impossible.”

“Every goddamn theater around here is doing plays about social justice,” he complains. “Nobody knows what social justice is. How does it differ from justice? Social justice is basically mob rule: saying whatever the greatest amount of people in my group think is just is just and anyone who questions it is a philistine or a Nazi. The question of what really is justice has been occupying my people, the Jews, for about 6,000 years. It’s a very difficult question.”

As with theater so with cinema, he says. “Just like white people are not going to the movies to see movies about being white, I doubt that black people are going to the movies to see movies about being black. They know what it is to be black. So the question is, can you keep an audience’s attention? And can you do it through politics? Well, yeah, if you want to stage the Nuremberg rally.”

Raised on the South Side of Chicago and the son of a prominent labor attorney born to Polish Jews, Mamet has been in Southern California long enough to opt for a cardigan, a cup of hot tea and a crackling fire when we meet on an evening when the temperature barely dips below sixty degrees. I wonder out loud whether he had thought about leaving California at any point during the pandemic. Many others chose to; the Golden State’s population shrank for the first time in its history in 2020. “It’s a good question,” he replies pensively. Family and a wonderful home (factcheck: true) are what keep him in LA, he says, not that he thinks much of his neighbors: “We live among the most politically foolish and destructive group of individuals in the modern world… especially on the west side.”

If he were to move, where would he go? “Maybe Austin. Maybe Miami Beach. Those people like DeSantis. They’re smart. And they’re American. They get a kick out of being American.”

“The thing is,” says Mamet, warning me we’re about to take a detour, “I get around a fair amount, and people don’t give a shit about what color people’s skin is. It’s just not true. And women are not oppressed. This is the freest country in the history of the world. We want to go back, as Thomas Sowell says, and dress up in seventeenth-century costumes and pretend now is then? I remember segregation. I remember separate washrooms. It was dreadful. And people devoted their lives, and gave their lives, to stop it. And they did.”

Mamet has long reconciled himself to the consequences of admitting to his conservatism in Tinseltown. “We don’t really go to any parties,” he says. “But we found out that a lot of people we thought were friends turned out actually to be acquaintances. Then they downgraded themselves to opponents.”

“They used to say that the movie business runs on greed and television runs on fear. But now it’s all television, it all runs on fear,” he says. “People are scared to death. They whisper to me that they are conservatives. If they came to work with a Trump sticker on their car, or perhaps even an American flag, they’d lose their jobs.”

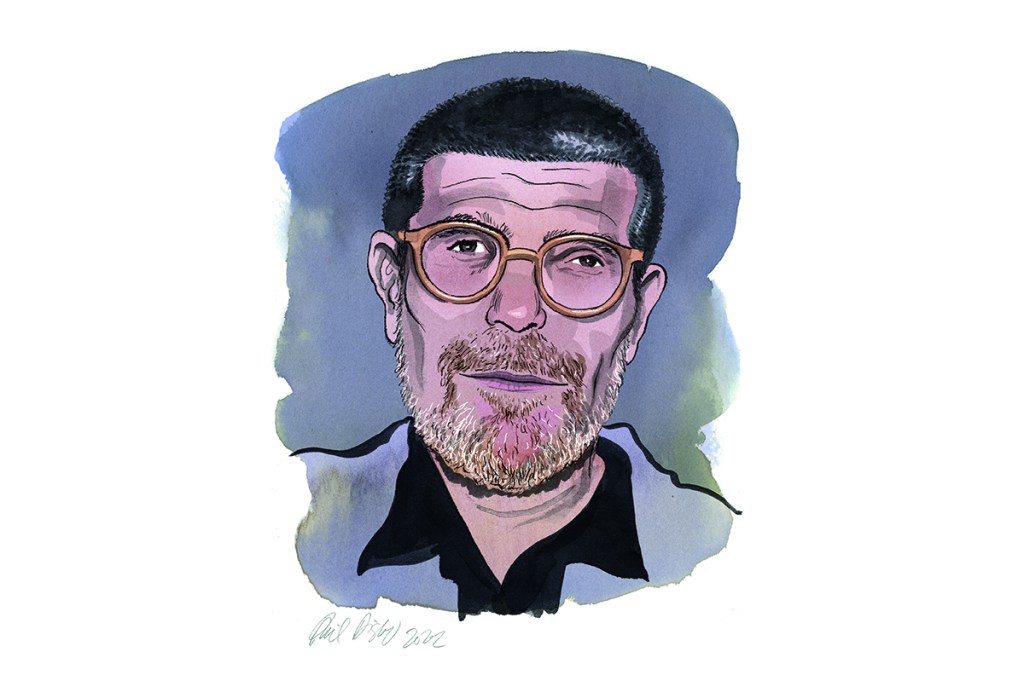

Talk to Mamet for more than five minutes and you notice he thinks, and speaks, in dialogue. Issues are weighed in an imagined back and forth. Arguments are tested out almost as conversations between characters. No matter the subject, you are talking to a playwright. And what would you expect from a man who made his name with brilliantly tight, naturalistic and memorable dialogue? Stocky, with closely trimmed hair, he still embodies his pugilistic style. But chatting in his living room, Mamet follows his thoughts where they take him; his answers are discursive and wide-ranging, a far cry from his work. Not that the lines are any less memorable, or that his conclusions any less blunt and unsparing.

If conservatives are an endangered species in film and theater, out-and-out fans of Donald Trump are something approaching a mythical creature: do they even exist? Well, yes. There’s at least one of them. Mamet is enthusiastic in his support for the former president. He draws flattering comparisons to “two other unlikely individuals”: General Grant, “who saved the Union after he got kicked out of the army for drunkenness and they called him back in,” and Winston Churchill, “who was out of office, out of favor and generally considered a madman, a warmonger and a fool.”

“Only guy who ever did anything for the Jews other than Harry Truman. And we had peace and prosperity. And they killed him,” says Mamet of the former president before drawing another unlikely parallel. This time with Laocoön, the priest who begged the Trojans to destroy the great horse rather than let it into the city before being dragged into the sea and killed by two giant serpents.

Mamet’s view of Washington is as unsentimental as his view of Hollywood: “People go into these professions to get power, and power to get sex, or sex to get power, money to get sex or power, and power to get money. That’s what these protected professions are all about… Trump was a countervailing force.”

“So what” would be a fair two-word summary of Mamet’s view of Trump’s various personal shortcomings. “A bunch of bullshit,” is his response to charges of irresponsible Twitter activity. Of Biden, meanwhile, he says: “If you ask someone what are three things you admire about Joe Biden, what will they say? There’s nothing to admire about him. His party — perhaps — won the election.”

Perhaps? “Well, perhaps they stole it. It’s certainly an open question,” says Mamet, who thinks “a little investigation was called for.”

I stick the pin back in that grenade and ask for a prognosis for America. “Every civilization dies,” he replies. “And no democracy ever lasted longer than 300 years.” In “Recessional,” the title essay and (appropriately) the last piece in his new collection, Mamet writes that “civilizations persist through intention” and calls for a “renewal of vows” for American citizens.

If Mamet’s mode is dialogue, there seem to be two Mamets talking to one another. One is Mamet the playwright, as sharp an observer of human folly as you’ll find. The other is Mamet the concerned citizen, increasingly angry about the condition of his country. In his dissection of American public life, he flits back and forth between wry bystander and committed participant.

As if to find something like a hopeful note to end on, Mamet offers up the possibility that the states might return to their proper constitutional role as the real centers of power and laboratories of government. But he hardly sounds persuaded by his own answer. “Who knows,” he says. “I used to think ‘I wish I’m going to live to be 150 so I can see what is going to happen.’ But now I think I’ll play these and go. I’m glad I won’t be around. My wife studies yoga and philosophy and I say I’m about ready to turn back into an elephant now.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2022 World edition.