It seems like the perfect socialist ideal: massive unemployment, inequality in income and jobs along with growing class divisions can all be met by a common income that keeps every family fed, housed and healthy.

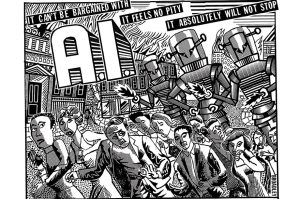

Such is the current debate that is engaging every country that fears the fallout from the Artificial Intelligence revolution that is likely to eliminate tens of millions of jobs – up to 33 percent of all jobs in the US according to a McKinsey study. At the same time, many students leaving high school or graduating from college may face the reality of never being able to work.

With social tensions across America already high, the idea of a Universal Basic Income for all seems like an attractive solution. To the left, UBI will be an answer to inequality and a safety net for all those suffering from AI fallout. To the right, UBI is a way of getting rid of bloated, costly and inefficient government welfare programs.

The idea of UBI was first mooted around 500 years ago in Thomas More’s Utopia and since then various philosophers from Thomas Paine, Bertrand Russell and Milton Friedman have all given the idea some credence. More recently, Andrew Yang, the Democratic presidential candidate, calls it a Freedom Dividend which may have a certain marketing appeal but doesn’t actually mean much. Bill Gates, the Microsoft co-founder and one of the world’s richest men, believes that UBI is inevitable, as do Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg.

The challenge confronting all these enthusiasts is to explain just how UBI might work in practice and where will the money be found to pay for it.

Despite its venerable age as an idea, no real studies have been conducted on UBI. That is now changing with experiments under way in Italy, Canada, the Netherlands, India and Finland.

In Finland, a two-year pilot program gives 2,000 unemployed Finns a guaranteed $600 monthly income even if they find work. The current program cuts the benefits for those who get a job and so acts as a disincentive. The hope is that the new experiment will encourage people to find work although just why those with a job should continue to receive a permanent government subsidy has not been answered so far. However, in the first year of the study, there was no increase in employment among those taking the stipend, although they did report feeling better about themselves.

The longest-running UBI experiment has been in Alaska which since 1982 has dedicated around 25 percent of the state’s oil revenues to the Alaska Permanent Fund. Each year, the Fund pays a dividend of between $1,000 and $2,000 to every man, woman and child in the state. The result has been mixed: poverty is among the lowest in the nation but unemployment is the highest. At the same time, a collapse in oil revenues has led to a halving of the annual dividend and political chaos in the state. Unless there is a dramatic rise in the price of oil, it seems certain that Alaska will have to raise taxes across the board to just pay for basic services, never mind sustaining their equivalent of the UBI.

Andrew Yang’s plan calls for the introduction of a 10 percent national Value Added Tax on goods and services and then offer all US citizens over the age of 18 a choice between accepting money from the existing social security system or accepting a flat $1,000 a month. Much of his plan seems to be based on fuzzy math and very optimistic projections. Given that Yang is stuck in single digits in most polls, his plan doesn’t seem to be resonating with voters.

The actual numbers for a national UBI program are daunting. If every American received an income of $10,000 a year, that delivers an annual bill of $3 trillion which is almost the entire amount collected in current tax revenue. Most economists argue that to pay for UBI would require the largest tax hikes in US history at a time when other programs (healthcare, social security) need more money to avoid going bust and extra funds are needed urgently or job training, education reform and infrastructure building.

What is clear from the debate is that UBI enthusiasts lack much data to support their idea and instead fall back on what might be described as the ‘feel good’ philosophy: if only people had real income security, they and their families would feel better and thus be encouraged to engage with job training and in finding work. For the right, any idea that will cut entitlement programs is seen as a good thing, especially if it can be argued that it will save money.

But for both left and right, the whole UBI debate seems to be untethered to intellectual, political or practical reality. Instead, there is an ill-defined and naive hope that UBI will solve whatever particular political bogeyman is brought to the party whether it be poverty, inequality or expensive government programs.

Whatever the political arguments, the reality is that tens of millions of Americans are expected to see their jobs go away by 2030 as the AI revolution touches every profession. Existing social programs have neither the cash nor the resources to meet the rapidly growing need and so, irrespective of their philosophical differences, both left and right will be forced to unite behind a common plan to relieve the expected suffering.

Inevitably, that will have to involve tax reform – Bill Gates favors a tax on every robot to help fund new social programs – and will have to include a new simpler safety net that will cut through the current bureaucratic nightmare. A tax system that is failing, social programs that are hopelessly inefficient and a growing group of Americans who are certain to need financial help. Is that a recipe for UBI? Maybe, but someone still needs to explain just how the economics of such a solution could make sense.