Read chronicles of ancient peasant life, or examine photographs taken a century ago. Behold castes, tortures, and endless annals of servitude and uncertain order. Backbreaking work and darkness fill short lives in a cruel world of grandees, subjects, and slaves. The injustices and trials of 21st-century life in this thing we call the US and West pale by comparison. Did this freedom and plenty just happen by accident? Or should we rethink what seemed to be political, economic and social triumphs as crimes against nature, and for good measure reimagine world history as a global casualty of Anglo-European rapacity?

History is in trouble. Less-than-progressive staff at historical societies, archives, and libraries have been retired or purged. Meanwhile, on campus, like fungus growing on dead wood, diversity forces plunder endowments. Creating highly politicized alliances and networks, they replace scholarship with emotive learning systems that sabotage arts and letters. Facing such travesties, protected by tenure and fat pensions, senior faculty detach to pursue their own often recherché interests and epicurean styles, ideally on leave or sabbatical in another country.

Academic history is far-gone, with anti-Western narratives and interlocking grievance studies funded by public, tax-supported colleges and schools being the rule. For subsidized radicals, history’s value is propagandistic. But it imprisons the field thematically inside parameters of race, class and gender, using specious post-structural methods.

Yet such studies are death at the box office. Between 2008 and 2017, the American Historical Association reported history experienced the steepest decline of all undergraduate majors, even factoring in “double majors.” Enrollments likewise declined. If “diversity requirements” were not in place, enrollments would have dropped even faster. Pandemic-related disruptions in enrollments are not yet quantified, but student disposition does not favor recovery.

In elite schools and colleges in the early 20th century, the study of Europe and US — their wars and revolutions, constitutions and political ideas, statecraft and economies and fine arts — replaced theology and the classics as the core of liberal studies. Historiography was exacting in method, based on artifacts, documents, numbers, and legal records, construed as objectively as possible. The craft required patient archival investigation, close reading, a good memory, and, often, multiple languages. Cautionary examples of civilizations’ rise and decline, prudence and folly, vice and virtue edified those destined to rule.

From the 18th and 19th century on, archaeologists and antiquarians from Europe and the US combed the world and its records to understand past societies. Their great compilations, chronicles and archives stand fast in research libraries and rare book collections. Unlike science, new historical discoveries are limited. The surveys, monographs and interpretations of past scholarship fill rooms and rooms. But why read any of it and commit it to memory when presuppositions are white, patriarchal, and ethnocentric? Historians by the end of the 20th century had to find something novel to keep campus research engines and university presses in motion. Whether or not rigorous methods of the past and the enduring authority of this corpus contribute to today’s postmodern antics and ahistorical advocacy is an open question.

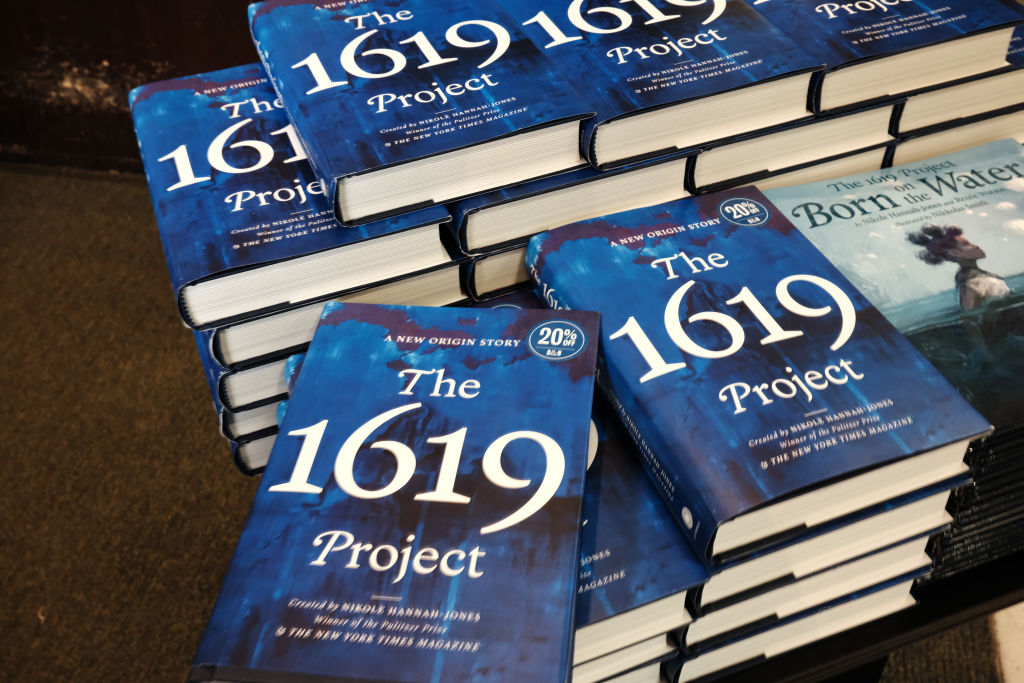

Writing “social history” once promised “new perspectives.” But the “new perspectives” rapidly iced out counterviews with near-Bolshevik brutality. A centralized, cohesive and disciplined academic movement focused on overthrowing canonical scholarship and its adherents. The revisionists’ early targets included capitalists, anti-communists, and Protestant elites. Howard Zinn’s history embodied the hard-left outlook and spirit of his day, an activist role since eclipsed by the racialist Nikole Hannah-Jones. Jones is the so-called architect of the New York Times’s widely distributed “1619 Project.”

In the 1990s, race, class and gender took thematic control of the field. Political and economic history have since largely left campus. What remains of them has been weaponized on behalf of “diversity.” Intellectual, diplomatic, and constitutional history — topics that once dominated the field — have likewise shrunk. Military history — which enjoys a huge amateur audience — is nearly extinct.

From 1975 to 2015, women’s and gender history expanded at the fastest rate of all specialties, followed by “cultural studies.” Asian-American and foreign students — a rising share of undergraduate admissions at selective colleges and top research universities, where history has long been a popular subject — constitute history’s most pronounced losses. Reversing trends, women’s interest in the subject is now falling.

Amid this state of affairs, American Historical Association president James H. Sweet published a column in the organization’s magazine last month on “presentism.” To historians, presentism means judging the past by way of contemporary attitudes and bias, and often condemning past generations for failure to align with today’s progressive values, standards, and norms. Sweet suggested that many academic historians pursued “the idea of history as an evidentiary grab bag to articulate their political positions.” Is the “1619 Project” legitimate history or something else, he dared posit. Sweet learned the hard way: these are forbidden thoughts.

The “1619 Project” seeks to “reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative,” including its economic might, industrial power, and political constitution, its editor has said. Indelibly tainted by their ancestors’ cruel racism, white Americans owe reparations and much more to their black victims, according to Jones and her school of thought.

Fellow historians flamed the AHA Twitter account. Many called for Sweet’s resignation. Sweet instantly groveled. “In my clumsy efforts to draw attention to methodological flaws in teleological presentism, I left the impression that questions posed from absence, grief, memory, and resilience somehow matter less than those posed from positions of power,” he babbled, ending pitifully, “I hope to redeem myself.” This craven surrender, as the National Association of Scholars’ Peter W. Wood observes, closes academic history to self-repair and makes the 1619-style mindset unassailable.

Under such circumstances, who would pursue a history doctorate and career without appropriate ascriptive credentials and a woke-accordant state of mind? The instructional job going forward, it appears, is to decolonize the curriculum and propagate race-hate, gendered knowledge, and the rest of it. Any deviation will be punished.

On campus, the quality of scholarship throughout the humanities and social sciences pales beside intersectional status and loyalty to the cause. Institutional caprice haunts any tenure-track professor, no matter how dazzling or original the intellect. Tenure, grants, book contracts, fellowships and the dean’s discretionary goodies go to the politically faithful and obedient.

No thank you, sensible young men and women of mind and judgment say, as they head for STEM or economics lectures. Can you blame them? Medicine, law, engineering, technology, and finance promise advancement based on talent and insight, not on blind allegiance to highly contestable social axioms and whims of tenured tyrants.