The reason the British people love the Queen, and are willing to die for her, is that they can understand what she is about, in a way that they cannot understand what the constitution, cabinet and parliament are about, or the Courts of Justice or the Bank of England, or any of the other abstractions which comprise our so-called system of government. Monarchy is credible, as Bagehot said, because it is personal. Seeing is believing. That is why all the old royal ceremonials are important: not because they are incomprehensible and mysterious, but because they are intelligible and familiar. All that talk about the magic of monarchy is very misleading. The strength of monarchy lies in the fact that of all forms of government it is the least mechanical and the most recognizably and intimately human: government made of flesh and blood in the shape of a particular family, the more ordinary the better. Monarchs get married, have babies and die (unlike ministries, which are instructed, reshuffled and such like), and it is because these familiar activities require no effort of the imagination to appreciate and no great intellect to comprehend that ordinary British people feel more safe to see sovereignty lodged there than somewhere else.

Peregrine Worsthorne, “Queen and Commonwealth,” December 3, 1983

Birth

Universal pleasure has been caused by the birth of a daughter, on Wednesday, to the Duke and Duchess of York. The new Princess is third in the line of succession to the Throne, coming after the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York… It will be very agreeable to the nation if the child is given a characteristically English name; the marriage of the Duke of York to a British subject instead of to a foreign Princess has been as popular for the principle it embodies as Their Royal Highnesses are popular for themselves.

News of the Week, April 24, 1926

Early life

Princess Elizabeth was born in a house in a London street, and spent most of the first ten years of her life in a house in another London street, Piccadilly, with cars and buses and taxis — all that makes up the swift and shifting life of London — speeding past its windows day and night. It was the comfort of an English home like a thousand others, rather than the luxury of a palace. That we have known relatively little hitherto is matter rather for satisfaction than regret, for it means that her childhood has been wisely guarded and sheltered, and her personality allowed to develop as it would, unstrained by any undue consciousness of status. “The fierce light which beats upon a throne” probably oppresses King George, and oppressed his father, but youth should be spared that white illumination so far as may be. The Princess may have years of service as Heir Presumptive before her. She may at any moment by the caprice of fate be summoned to the most exalted position in these realms. We can rejoice to know how well the preparation for either lot has been achieved by a training that has never threatened to dim the freshness or mar the simplicity of her girlhood.

Wilson Harris, “Our future Queen,” April 16, 1943

Eighteenth birthday

Till this week the death of the King would have involved a Regency. Now the succession would be immediate and automatic; when it is realized what responsibilities that would lay on the Princess’s young shoulders, the reason for thankfulness that a change of sovereigns is in all likelihood far distant is doubled. It is reassuring, none the less, to know that whenever the moment comes for assuming the burden the new Queen will be equal to it. About that there can be no doubt.

A Spectator’s notebook, April 21, 1944

Engagement and marriage

The Princess could hardly have made a choice that would raise questioning or doubt, but there is a special place in English hearts for a sailor and a sailor’s bride.

News of the Week, July 11, 1947

Times are changing. That the royal couple should be spoken of commonly by the people and sometimes by the Press as simply Philip and Elizabeth is symptomatic. “That divinity doth hedge a king” hedges it no longer, and it is far better so. Between sovereign and people there is a new familiarity that in no way connotes diminution of respect. Times may change more still. The spirit of egalitarianism is in the air. To that even royalty may have in some degree to adapt itself.

Leading article, “Princess and wife,” November 21, 1947

Death of George VI, accession and coronation

It will be fully time, when this week is over, to leave the past to be past, as it must be, and think of what Mr. Churchill called on Monday “the fair and youthful figure, Princess, wife and mother,” who is now the Sovereign of these realms. To her, our most gracious Sovereign Lady, Queen Elizabeth, our service is now due. She will be to the nation all, and in some ways more than all, that her father was. In the words of her message read in the Houses of Parliament on Monday: “He has set before me an example of selfless dedication, which I am resolved, with God’s help, faithfully to follow.” That the example will be followed unswervingly no one questions. There has been talk of a new Elizabethan, or a new Victorian, age. There will be neither. History does not thus repeat itself. But the Queen, in her own person, by no arresting word or deed, but by merely being what she is, could work a moral miracle through the land.

Leading article, “Queen and nation,” February 15, 1952

No monarch ever came to the throne so buoyed up by general popularity and affectionate interest as Elizabeth II… Now her coronation approaches. None before has put such a fever on London… The streets are bright with banners and with… devices which well match the rising tide of exhilaration; householders are putting out more flags; great areas of central London have disappeared behind scaffolding; enormous crowds swarm each evening outside Buckingham Palace and pack the processional route; the mood of holiday grows more intense hour by hour. There are those who still protest their determination to get away from it all and spend the day in the country, but the joke already wears a thin and irresolute expression… Perhaps there was a time when it was reasonable to question the wisdom of spending quite so large a sum of ingenuity and money on the elaboration of the event, but the public’s reaction should long ago have convinced the objector that there was as much sense in his objections as in protests against the heat of the sun.

Leading article, “Coronation fever,” May 29, 1953

Financial plight

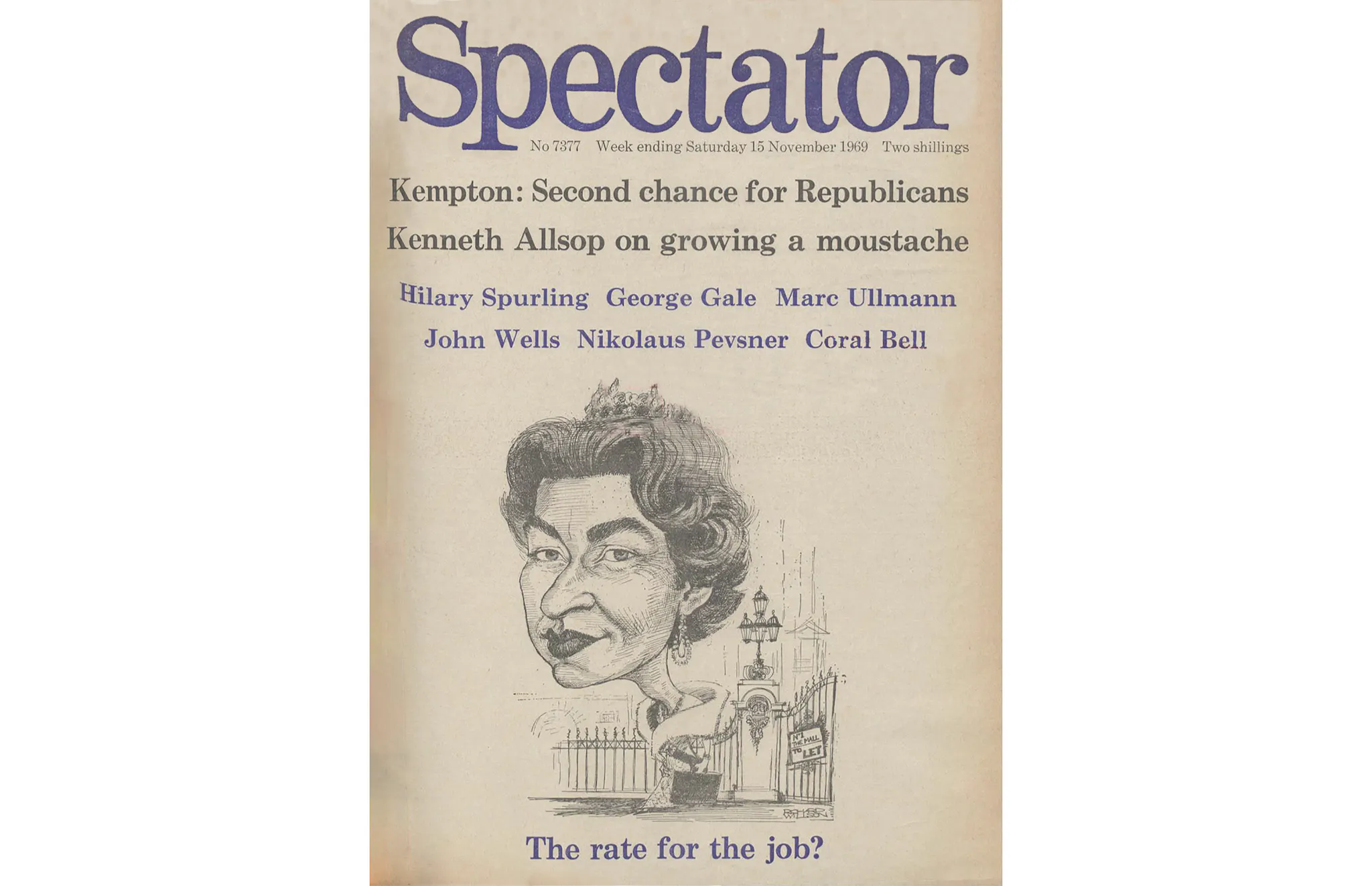

The Queen, although short of income, is lavishly endowed with capital assets (which is one reason why the royal family lives a life of middle-class simplicity amidst settings of palatial grandeur), and an annual sale of, say, some of the priceless works of art her predecessors acquired over the centuries, would transform the whole position. But this is a course of action which, understandably, she has so far refused to countenance. And rightly so. For the monarch’s role is a public one, and there is no suggestion whatever that, in carrying it out as it is understood in this country, the Queen has been in any way extravagant.

Leading article, “The rate for the job,” November 15, 1969

Abroad

All around the world excitement is mounting as the preparations go forward for the reception of the Queen in her first great tour of the Commonwealth… The Queen is young. She, with her husband, has shown a capacity for enjoying herself which is not least among the things that make her charming… The best parting word is the natural one to address to any young woman off on a journey round the world — “Enjoy yourself.”

News of the Week, November 27, 1953

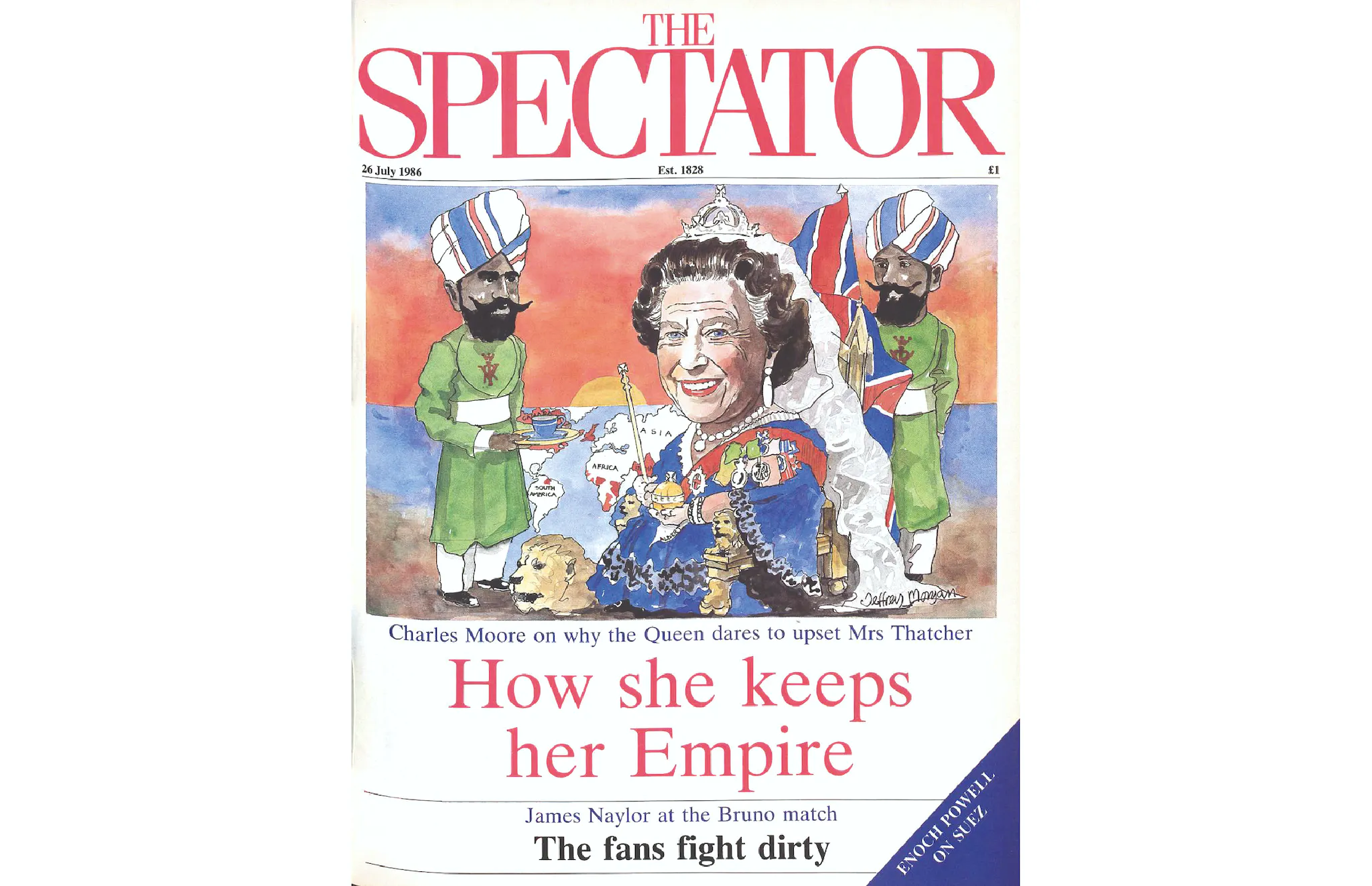

What is even more remarkable than the Queen’s readiness to adapt (which, after all is part of the job of a constitutional monarch), is her tenacious adherence to the idea of the Commonwealth… She was brought up to reign over a great Empire, and although the jewel of India was lost in 1947, neither political party, until the late 1950s, expected anything like such a swift or complete decolonization of Africa as then ensued. The Queen’s father had been prevented by war and illness from visiting many of his possessions; it was his daughter’s task to repair this omission… Ever since Victoria, British monarchs had regarded the colonies as places for which they were particularly responsible… The Queen was trained in this tradition. She was also trained to be a constitutional monarch. As the circumstances of the twentieth century began to threaten the Empire, she therefore had to accept the change and make the most of the euphemism which was devised to replace it.

Charles Moore, “The Queen’s very own Empire,” July 26, 1986

Less than four months away from her Diamond Jubilee — only the second in history — we still tend to forget that we have the oldest monarch (eighty-five) and oldest consort (ninety) in history. We see a monarch who is reassuringly unchanged — and unchanging — in an uncertain world. It is an integral part of her appeal, at home and overseas. In Australia right now, the republican tide is out. Invited to field a “royal” phone-in on national Australian radio earlier this week, I was struck by the consistent level of affection for the Queen. In half an hour, I encountered only one and a half republicans. It could have been Radio Royal Berkshire.

Robert Hardman, “Yes Ma’am,” October 22, 2011

What accounts for her international popularity? So broad is its sweep that we often forget how remarkable it actually is. When the British Empire crumbled, global opinion might just as well have swung the other way: “You’re no longer queen of us, so why should we feel any kind of goodwill toward you?” could instead have been the general feeling. This has patently not been the case.

Perhaps it lies in Elizabeth’s poise and dignity during the years of decolonization. As piece by piece the Empire broke off, Elizabeth remained a binding symbol, a kind of centripetal force. People may point out that she didn’t actually do much, but that is precisely the point. She didn’t emote, she didn’t sentimentalize, she didn’t vulgarize. She just held herself together while everything else gave way. Forget the Lloyds bank spin-off or the possible exit of peripheral nations from the eurozone — during her reign Elizabeth II calmly oversaw the biggest break-up of an enterprise the world had ever seen.

Clarissa Tan, “Queen of the world,” June 2, 2012

Queen and Church

Like the first Elizabeth, she is not interested in putting windows into men’s souls, merely in ensuring that she should not encounter practices which she finds uncongenial. On one occasion a new incumbent of the chapel attached to Royal Lodge asked if he could wear a chasuble. “If you like,” came the reply, “so long as it doesn’t happen when I’m here.” This pragmatism is typical: a clergyman’s liturgical background does not greatly matter if he follows the rules and — a very important point — preaches “a decent sermon.” The royal family has always set great store by “a decent sermon.” In the reign of George V, preachers were instructed by the King’s private secretary to speak for fourteen minutes: anything less would look like laziness; anything more could be a bore. That advice probably holds good today.

Damian Thompson, “A service fit for the Queen,” May 5, 1990

Dress

The Queen and God are now the only people in whose presence women are expected to wear hats — and not even God, I think, insists on a large hat.

Jo Grimond, “Hats off to Enoch,” January 28, 1984

The annus horribilis

What began as a celebratory year for the House of Windsor, with the fortieth anniversary of the Queen’s accession, has turned into its most traumatic since 1936. Worse, perhaps: for that intense drama was played out in months, after Edward had become King. But the tragedy of the Wales’ marriage now looks set to run and run, as farce, scripted by tabloid newspapers whose profitability has come to depend so much on this one sad story. No wonder the Queen, at a lunch on Tuesday to celebrate her forty years on the throne, described 1992 as an annus horribilis, which she would not look back on with “undiluted pleasure.”

Had we a properly austere constitutional monarchy, confined to a dignified sovereign and heir, none of this might matter. It has survived worse. But the Queen and her advisors have allowed the monarchy to become confused with the royal family. It has proved a mistake to follow her father in encouraging the notion of a “family” monarchy, expected to act as a paragon of Christian family life.

Anthony Holden, “An annus horribilis,” November 28, 1992

Monarchy is essentially a personal affair and the monarch will be judged by her subjects as to how she copes with this potentially highly damaging rift in her family. What, to adapt the line in Richard II, must the Queen do now?

Humanity and compassion should be the keynotes in handling the sundered royal family. This is not the time for self-pity (Her Majesty is not the only one to have had an annus horribilis) or for the icy Teutonic stiffness of her grandmother Queen Mary or even for the zesty “Let’s-pretend-it-isn’t-happening” attitude of her remarkable mother, Queen Elizabeth.

Make what you will of the symbolism of Windsor Castle, from which the dynasty took its new name in 1917, being burnt; and while the fragile barque of the “royal family” may have been dashed against the rocks by the intolerable pressures of modern matrimonial strife, the monarchy must survive. It surely will do so if the Queen, the Prince of Wales and the Princess of Wales can now be left in comparative peace to work out a modus operandi.

Hugh Massingberd, “But the show must go on,” December 12, 1992

Diana’s death

The monarchy, which has survived civil wars, invasions, assassinations, world wars and abdications, will even survive Kitty Kelley and its present temporary unpopularity over its perceived ill-treatment of Princess Diana. Despite the obituaries of the monarchy already being written in the left-wing press, the Queen will probably, especially if she has anything like her mother’s longevity, be looking back in two decades’ time and agreeing with Mark Twain that the reports of its death were an exaggeration.

Andrew Roberts, “The Princess and the Royal Standard,” September 6, 1997

The real significance of the flowers and the outpouring of grief they represent is how they will affect the monarchy. It is not enough to say, as Earl Spencer did at the funeral, that Diana’s influence was achieved without the help of her royal status. Nor is it enough for the royal family to believe that such a volume of flowers is also meant for them.

The Queen’s speech was perceived by many as icy, grand and remote… [There is] a profound feeling that Diana received shabby treatment from the royal family and that recognition of this must be made by acknowledging her virtues and incorporating at least some of her outlook and popularity in the future monarchy… There is a cry for change among the tears of sorrow.

Rory Knight Bruce, “What the crowds want now,” September 13, 1997

Since the death of Diana, a vocal chunk of the population has been calling for a “modern” monarchy without any clear idea of what that means. Any evidence of the common touch from the royal family in general and the Queen in particular has been trumpeted as evidence that the monarchy has learned its lesson. What this sensationalism obscures is the real modernization process and the fact that it has been under way for much longer than people think. But then, style makes a better royal story than substance.

Robert Hardman, “More signings for Ma’am United,” October 3, 1998

Sense of humor

Derek Draper’s story about Clare Short’s pager going off in front of the Queen (“I do hope it wasn’t anyone important”) reinforces my suspicion that behind that sucked-lemon expression Her Majesty has a wicked sense of humor. And it’s not just the clothes. At the recent re-opening of Broadcasting House she encountered Terry Wogan. “Ah,” she said, “I was listening to you on the radio this morning.” Legend has it that as the Greatest Living Irishman’s cheeks flushed with pride, Her Majesty delivered the follow-up: “Tell me — have you ever done any television at all?”

Rory Bremner’s diary, November 15, 1997

The Golden Jubilee

Should the Queen live as long as her mother, we shall yet have a Diamond and a Platinum Jubilee. Perhaps by the time those events come around we shall have woken up not just to their temporal remarkableness, but to the astonishing record of the Queen herself. There are too many signs, especially at the top of our country, that what she is and what she does are lamentably taken for granted. No elected head of state would survive, or tolerate, the constant scrutiny, the sheer offensiveness, the irrational prejudice, the decade upon decade of demands, responsibility, pressure. We should be grateful that for these fifty years God has saved the Queen; and be a damned sight more thankful for it, and her, in the years that we hope remain to her.

Simon Heffer, “In the line of duty,” January 5, 2002

It is a good job the anti-monarchists had their say early, for the Jubilee is in danger of becoming a success. The supposed indifference towards the Queen and her reign is straining under the reality… If it is true that the public no longer quite feel the little teardrop they felt upon the sight of a royal carriage in 1952, the decline in affection for royals is as nothing compared with the collapse in respect for our elected representatives.

Leading article, “Republicans in retreat,” February 2, 2002

Her eightieth birthday

The Queen has succeeded simply by being herself, a model of discretion and dedication to her country. Even last year, aged seventy-nine, she carried out 378 public engagements in the UK and no fewer than forty-eight official overseas visits. As a constitutional monarch and therefore above party, she is impeccable. People might surmise that she could be unhappy about the demolition of the constitution by New Labour, but they do not know.

There is, however, a saying that sounds very like the Queen. Amused rather than offended by Cherie Blair’s public refusal to curtsy, she is held to have said: “I can almost feel Mrs. Blair’s knees stiffening when I come into the room…”

Sarah Bradford, “The Queen has succeeded simply by being herself,” April 8, 2006

The Diamond Jubilee

I’ve sometimes wondered — what does it feel like to be queen of the world? It must be a terrifyingly lonely experience. At the center of this huge Jubilee jamboree lies just a single, and singular, woman. Elizabeth must know she’s appreciated not only for the post she upholds, but also for her person. For, more important perhaps than being a queen, she strikes me as being a lady.

Clarissa Tan, “Queen of the world,” June 2, 2012

Well it’s all too terribly, terribly exciting: sixty glorious years on the throne of England and almost more than that in my consciousness. A question that often surprises me is: “Why are you still working? Wouldn’t you like to just lie around and put your feet up?” The very idea! I’m sure no one would dare address such a fatuous remark to the Queen, who’s in robust health. She’s the one to whom people should be asking: “What’s your secret?” Don’t tell me shaking hands with over 4,000 people a year, standing still for hours on end without showing a flicker of discomfort, and attending over 400 functions without showing the faintest hint of ennui, is not an outstanding achievement by itself, without counting the innumerable times she has led the country by example and sound advice. When she bestowed upon me an OBE in 1997, I had already met her several times and she greeted me with such a warm smile that I felt as though we were rather good acquaintances. There’s only one question I’ve been dying to ask her: “Ma’am, what’s in the handbag?”

Joan Collins, “The Queen and I,” June 2, 2012

In the pub

The Queen, year in, year out, does the same things again and again. Amazingly, in her sixty-one years as sovereign, traveling the United Kingdom, the Commonwealth and the world, the Queen has only ever made two unscheduled stops. One was in 1981, when the royal Rolls was caught in a snowdrift in Gloucestershire and Her Majesty took refuge in a roadside public house. I visited the Crossed Hands pub in Chipping Sodbury this week. I went in by the front door and had an egg sandwich and a coffee. The Queen got in via the fire escape and had chicken liver paté, Dover sole and a gin and tonic.

Gyles Brandreth’s diary, November 9, 2013

Covid crisis

What strikes me now is how, in a nation alleged to have been so low on trust and respect, we have been quietly storing it away even while we pretended otherwise. When a real problem came, there wasn’t much time for the people with imaginary ones. At no stage was there a demand for grievance studies professors to address the nation. As the virus spread, absolutely nobody called for a press conference of social scientists. We wanted to hear from politicians clearly trying to do their best. We wanted to hear from medical experts. And finally we wanted to hear from the Queen, who remains the person best placed in our national life – or any nation’s life – to put in context what will hopefully soon recede in the national memory.

Douglas Murray, “Our flawed species still stands a chance,” April 11, 2020

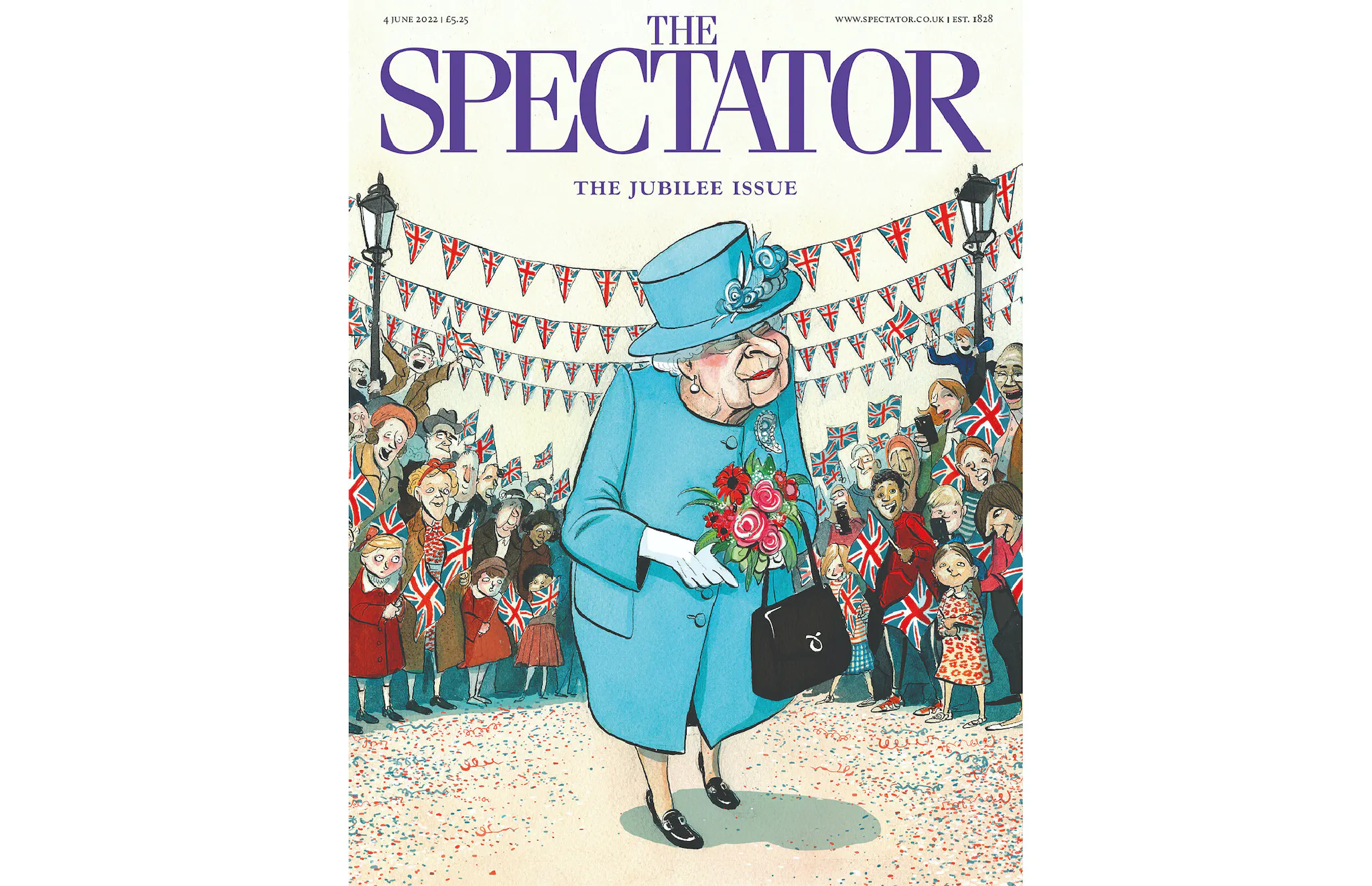

The Platinum Jubilee

In celebrating Her Majesty’s seventy years on the throne, we will be touched by footage of a young mother of two taking on the most glamorous but impossible job in the world at the age of twenty-five. Yet the enduring strength of the institution she leads, despite numerous challenges, is not just down to lucky genes and longevity. It is precisely because of her intuitive capacity to adapt, and her quiet insistence on following her own instincts, that the monarchy is as robust as it is today. Indeed, by the standards of her forebears, we can even call her a radical.

She has presided over monumental change. And she has not just been an interested bystander. She has been a player.

Robert Hardman, “The quiet radical,” June 4, 2022

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.