In 2022, a year after its centenary, there is the chance that Northern Ireland could end up with a nationalist, republican, Sinn Féin first minister.

The latest survey of popular opinion in the province, polled by LucidTalk, currently has Sinn Fein as the largest party on 25 percent, nine points clear of the DUP who have slumped to 16 percent – from around 30 percent at the 2019 Westminster election. Meanwhile, there has been a slight upswing in the performance of the Ulster Unionists and Traditional Unionist Voice. The middle ground Alliance party are on the same level as the DUP, while the moderate SDLP appear to be a minority taste among nationalists, and are stuck on 12 percent.

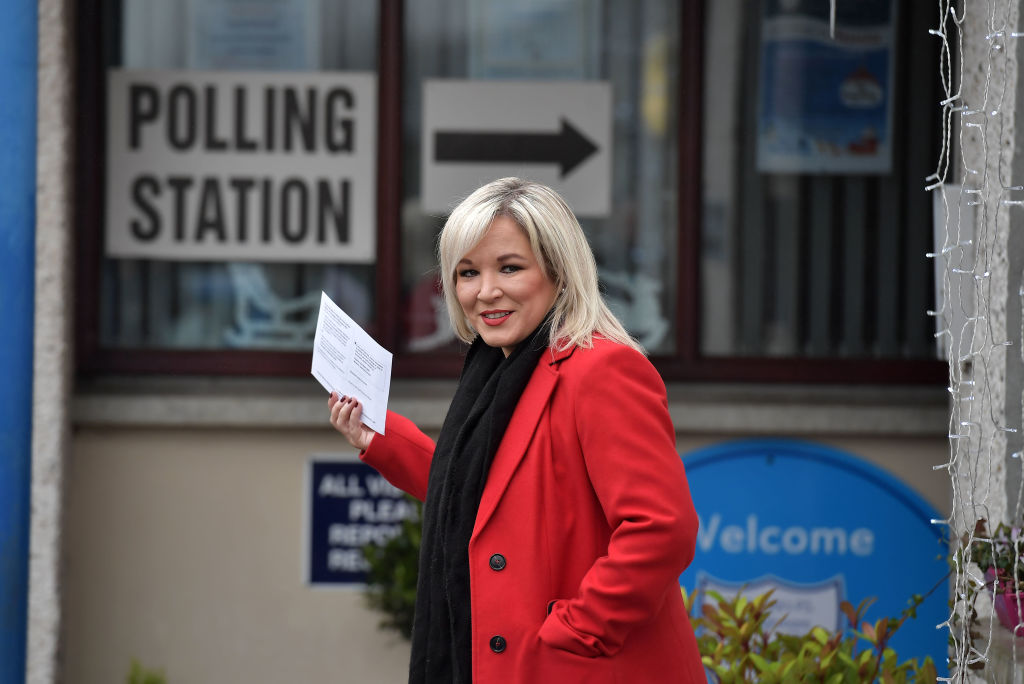

As with all polls, there are the usual caveats; the next scheduled Assembly election is a year away and plenty can change before then. And this is, of course, just one poll. But the suggestion that Michelle O’Neill could be first minister of Northern Ireland will have caused furrowed brows in Belfast, London and Dublin.

As part of the 2006 St Andrews appendix to the Belfast Agreement, the party with the most Assembly seats automatically becomes first minister, although joint government exists through the ungainly conjoined ‘Office of First and Deputy First Minister’. In the past, the DUP have approached the Assembly elections by tub-thumping and asking the electorate if they want republicans like Martin McGuinness running the show. That was enough to get the vote out then, before Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol rendered asunder the party’s electoral coalition.

Sinn Féin becoming the largest party in Northern Ireland, and taking the first minister role, would be a profound challenge across Ireland and Britain alike. Symbolically, a unionist not being first minister would create an existential crisis, especially for the DUP, following the loss of unionism’s majority at both Stormont and Westminster.

For Downing Street, it would be another irritation from what they are increasingly viewing as England’s troublesome Celtic periphery. Though the Northern Ireland Executive is nominally meant to be a paragon of cross-community consensus, the dynamics of the game would change if the biggest party were committed to the region being extracted from the supposed yoke of Westminster rule, as in Scotland. Things would not be easy for the Irish government either, if their primary opposition in Dublin suddenly ended up running the show in Belfast. The reunification chatter from nationalism would become deafening on both sides of the border.

The question now is how unionism, particularly the DUP’s recently crowned leader Edwin Poots, will react. This poll demonstrates the scale of the challenge he faces personally; the vast majority of DUP voters favored his vanquished rival Jeffrey Donaldson. It also shows how riven unionism is as a movement, a direct consequence of the DUP’s failures regarding the Protocol and its inability to understand Northern Ireland’s changing social undercurrents.

The UUP, sitting on 14 percent and Traditional Unionist Voice on 11 percent, are up on previous showings in this poll. Some have already suggested, and will continue to suggest, that unionist parties in Northern Ireland should band together to defeat their common foe. But that is unlikely to happen, such is the deep sense of distrust between the parties.

Could the DUP bring the show — in this case the Stormont institutions — down before the election rather than suffer the ignominy of being the junior partner in government? This avenue is open to Poots but it would confirm his critics’ assumption that under his leadership the DUP is doomed to become nothing more than a revanchist entity. The subsequent vacuum caused by the collapse of the devolved government could also prove a boon to those on the political fringes who are already spoiling for further chaos.

In a normal political environment being knocked off the top spot would perhaps be an effective shock therapy for the DUP and unionism more generally, setting the party straight after years of strategic and policy atrophy. But unlike in a normal democracy, playing second fiddle in a mandatory coalition is unlikely to have that cleansing, scourging impact. Unionism is in such a maudlin state right now, it would probably prefer to engage in one endless pity party.

The obvious solution is for better candidates and better policies to make unionism a more attractive and successful prospect. Small wonder, therefore, that some consider the UUP’s new leader Doug Beattie as a real and present danger to the DUP’s near two-decade stint as unionism’s biggest party.

It is deeply depressing that 25 percent of the electorate feel that Sinn Féin, a party which has firm links to the Provisional IRA Army Council, best represents them. That says much about the current state of northern nationalism as well. But Sinn Féin’s ascent also has much to do with the lack of a convincing, coherent unionist narrative which is electorally appealing enough to combat them and win more voters. If Sinn Féin ends up on top in 2022, unionism only has itself to blame.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.