Some commentators have already noted the strange homology between Russia’s evocation of “secret bioweapon labs” in Ukraine and the US evocation of Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction, which in both cases were used to justify military attack.

It’s not that the US was unsure if Saddam had WMDs; they positively knew he did not have them, which is why they risked a ground offensive in Iraq, rather than sticking to air bombing.

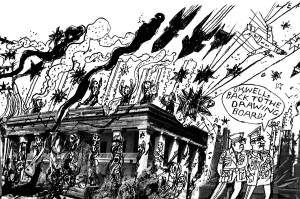

The nonexistent Iraqi weapons of mass destruction perfectly fulfill the role of a “MacGuffin” in Alfred Hitchcock’s films. A MacGuffin is “an object, event, or character in a film or story that serves to set and keep the plot in motion despite usually lacking intrinsic importance,” per Merriam-Webster.

Usually, the MacGuffin is revealed in the first act, and thereafter declines in importance. Incidentally, one of the most famous Hitchcockian MacGuffins is a potential weapon of mass destruction — bottles with “radioactive diamonds” in the film Notorious.

Iraq’s WMDs were an elusive entity. When UN inspectors were searching for them in Iraq, they expected to find them in the most disparate and improbable places, from the (rather logical) desert to the (slightly irrational) cellars of the presidential palaces. They were said to be present in large quantities, yet were mysteriously moved around constantly, and unable ever to be found, these WMDs became all the more dangerous.

In the Ukrainian war, Putin’s MacGuffin is the claim of secret bioweapon labs in Ukraine, allegedly organized and funded by the US to develop poisons that transmit human sicknesses. They are evoked as the reason Russia does not just plan to occupy the southeastern area of Ukraine where there is a strong Russian minority, but intends to seize all of Ukraine and destroy these labs.

Again, though, I claim Russia positively knows there are no such secret bioweapon labs in Ukraine full of dangerous poisons. If such labs were there, Russia would act in a different way, with much greater urgency, directly attacking these labs or trying to occupy them with elite parachute units.

To avoid a fatal misunderstanding, let me be clear that this does not mean there are no bioweapons being developed in secret labs. All big countries have them, of course, and our media are right in treating these Russian accusations as a dark hint or threat that they themselves may use bioweapons. The Ukrainian war can take many further turns for the worse, not just the recourse to nuclear weapons. To list some examples: use of bioweapons; use of gases that hinder brain function; a full digital attack on the cyberspace of the enemy.

We’ve recently seen evidence of a dimension of truth surviving in Russia, as police arrest demonstrators who protest the war in Ukraine. In one instance, which has gone viral on social media, a woman was arrested by Russian police for holding up a small piece of paper that reads “two words” (“два слова” in Russian) referring to the forbidden slogan “no to war” (“нет войне”). Here we see that even absence of expression has the power to refer to something specific.

Russian police also arrested demonstrators protesting with blank signs, a substitution that works because everybody knew at that point that publicly rejecting the war against Ukraine is prohibited in Russia.

Such scenes remind me of a similar censorship case from my youth in 1970s Communist Czechoslovakia. At that time Martina Navratilova was the world’s top tennis player. She emigrated to the West and became a non-person, even for the Czech sports media. When she reached the semi-final in a big international championship, a Czech sports daily reported on it with the title, “The four semi-finalists known,” followed by only three names. Navratilova was simply ignored, although the title implied four players. She was “present in the mode of absence” (to use the structuralist jargon).

Just as blank protest signs and an unnamed tennis star, though themselves irrelevant, served to set and keep their respective plots in motion, so too do claims of secret bioweapon labs work as a MacGuffin in Putin’s favor.

Putin’s court philosopher Aleksandr Dugin said in a recent lecture that the attack on Ukraine was Russia’s desperate attempt to make its message heard in the West: after twenty years of futile attempts to be heard and taken into account in a peaceful way, war was the only way left open to Russia.

War was inevitable for Putin, but he needed an excuse. Expect the secret bioweapon labs ruse to decline in importance as the war wages on.