When Russians headed to the polls last week, the Duma election results were never in doubt: Putin’s United Russia party won two-thirds of the seats, while the rest went to the tame ‘systemic opposition’. But even if the outcome wasn’t a surprise, the manner of Putin’s victory should ring alarm bells about what happens in Russia when he eventually departs.

The Kremlin ‘won’ the Duma elections insofar as United Russia received the number of seats it wanted. It did this on just 50 percent of the vote, down on previous elections, with widespread violations, and at the cost of what little credibility the electoral process still enjoyed.

In regimes like Russia, elections are not for the people, but for the autocrats. The authorities turn any election into a vote for something, rather than a choice from among several options. But even the semblance of reality and unpredictability with which Russian elections under Putin were once carried out is no more. The pretense of democracy has all but disappeared.

Egregious ballot stuffing, a crackdown on opposition candidates, and a litany of dirty tricks deployed against the Navalny movement’s smart voting campaign — which told voters which candidate had the best chance of beating the United Russia candidate — were all features of this election.

Putin’s continued crackdown on the Navalny movement is nothing new. But by crushing his opponents — and political life more generally — so thoroughly it makes it difficult to see how any transition of Putin from power can happen smoothly, whenever that time does come.

Last year, the Russian government brought in a raft of constitutional amendments that allow Putin to stay in power until 2036. But these changes were also intended to pave the way for a more collective, parliamentary, system to replace him. The handling of the elections this weekend, however — and the sheer scale of falsification and repression — directly undermines these efforts. Why? Because it refuses to allow any new system not with Putin at the centre of it to even begin to develop.

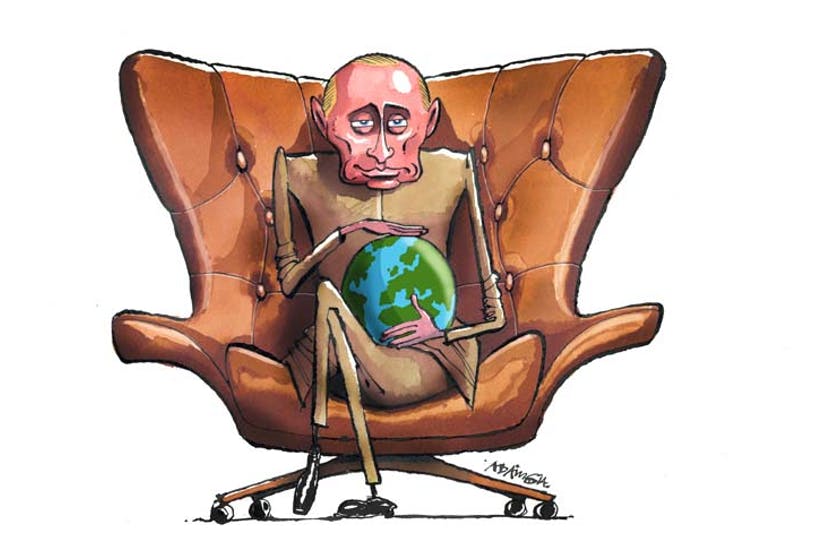

Personalized autocracies like Russia are always more prone to violent transfers of power than other types of one-party or military dictatorships. Paradoxically, the stability of the Putin regime depends on him, which is what makes his eventual departure such a troubling prospect. By minimizing political risks now it only increases them for the future, heightening the risk of serious political unrest after Putin steps down or dies in office.

Some in the West might wrongly view this as cause for celebration. They might want to believe that the end of the Putin-era would be a good thing, thinking it would inevitably lead to a pro-Western democracy. Such conclusions are not well-founded. Although there is a view that liberal beliefs are increasingly taking hold among younger generations of Russians, the evidence for this is spotted and far from overwhelming.

Even if young Russians are different from older generations, we should be wary of assuming a democratic Russia would inevitably be a pro-Western one. Many Russians, young or old, do not see the West as worthy of emulation. Navalny has previously voiced his sense of betrayal by the UK for harboring Russian dirty money, thereby facilitating the autocracy that has since imprisoned him in a penal colony.

He shouldn’t take it personally; it is a disregard that the UK also extends to its own citizens, as the British authorities continue to allow Russian politicians and Kremlin-backed businessmen to keep their money there. They continue to do this even as Russian state agencies have conducted chemical weapons attacks on Britain’s streets — as we were reminded of this week when a third man was charged for the Salisbury poisoning. This sends a message that the UK values Kremlin-linked money more than its own security.

Clearly the fallout of placing power and pecuniary gain over people and political ideals does not only affect Russia; it also has a direct bearing on UK security, undermines its standing around the world and fuels information campaigns that promote the UK and broader West’s moral failings.

Of course, Britain isn’t the only culprit here. There are many other reasons why democratically minded Russians will see Western politicians and companies as complicit in Kremlin corruption and political repression. In recent days, Google and Apple were accused of giving in to pressure from Putin’s regime after Navalny’s smart voting app was removed from their online stores.

The moral cowardice of the tech companies will not come as a surprise to many. But, fairly or otherwise, this hypocrisy will be interpreted as reflective of a broader Western vacuousness, not so terribly distinct from the cynicism and greed that typifies the Kremlin elites.

Life under Putin might be a depressing prospect for many Russians, but life after Putin is also a troubling prospect — and the most recent election gives a worrying indication of why.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.