When several Proud Boys attended a New Hanover School Board meeting about 175 miles from my North Carolina hometown, I was reminded of the night years ago when I woke to the sound of my mother weeping. Klansmen demonstrating outside our local library had made the late-night news.

The sight of those ignorant men outside the doors through which I’d recently exited with Where the Wild Things Are proved unbearable to my mother. She sent a blistering letter to the editor, inciting Klan supporters to call our house hoping to discuss, as one woman asked me before my mother snatched the phone from my hand, just what exactly her problem was with the Klan. And, oh, did my mother tell them.

The Proud Boys weren’t protesting anything literary at the New Hanover School Board meeting; they were registering their disdain for school mask mandates — a curious posture for men rooted in a long Southern tradition of masking. “The plan of attack if you want to make change,” explained North Carolina Proud Boy Jeremy Bertino to the New York Times, “is to get involved at the local level.”

On the surface, it’s a sentiment worthy of food banks and blood drives, but Mr. Bertino has reportedly sought out trouble in communities hours from his homestead in Gastonia, North Carolina. His comrades at the New Hanover meeting admitted to living 100 miles or more away.

In their crosshairs was a local group of radicals calling themselves the “lowercase leaders.” They had appeared at a prior school board meeting to harangue parents upset over critical race theory, though it doesn’t appear that any of them have children in the New Hanover school system. Their disruption was so thoroughgoing that the school board had to halt its proceedings. “This is not a battle zone,” the vice chair announced.

Oh, but it is, as are many American localities that have been subjected to turmoil from handfuls of people who have neither roots nor stakes in the communities they disrupt. Last fall, Reuters profiled an Antifa activist who boasts of having been arrested in Arizona, Virginia, Minnesota, and Florida over her favorite method of “deplatforming” opponents, which entails using “our hands and feet, maybe a piece of wood or something.” Violent wayfaring, she explains, is her “duty to humanity.” Recall Eric Hoffer’s dictum that it’s easier to love mankind than one’s neighbor.

The UN estimates that over 82 million people worldwide are presently displaced from their homes by violent conflict. The US is far from such calamity; no refugee caravans exited Portland after Proud Boy and Antifa goons assaulted one another on its streets. What’s more, when we scrutinize shoddy polls that claim an alarming number of Americans condone political violence, we find that the opposite is true: a vast majority prefers peace and compromise.

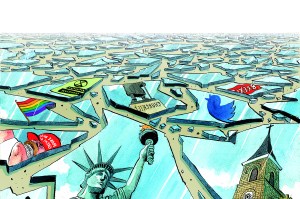

There are many non-violent mechanisms, however, by which interlopers can extend their conflicts into unsuspecting American communities. Every congressional district and electoral vote, after all, represents a potential tiebreaker in a decades-long battle to wield our vast federal apparatus. There’s simply too much at stake to let communities govern themselves.

This is why conservatives look askance at the more than $350 million in grants and “technical assistance” provided by Mark Zuckerberg and his liberal colleagues to voting precincts, the preponderance in areas where goosed turnout aids Democrats. Any scale-tipping that results from these interventions — or from subtle algorithmic tweaks conjured in the politicized bowels of Facebook or Google — affect not just national but state and local elections. Just the suspicion of them undermines faith in democracy and our concomitant willingness to abide by the will of the majority.

Monkeying with elections appears naive, however, compared to the work of billionaire Michael Bloomberg, who has funded lawyers to work in the offices of state attorneys general in order to advance his climate change agenda. With privatized public policy looming on the dystopian horizon, we may eventually long for the days when plutocrats were contented to launch themselves into space.

Bruisers and billionaires aside, the biggest community interlopers in America remain the array of swollen federal agencies embedded like ticks in our republic. Over the past decade, agency lawmaking has exceeded that of Congress by a factor of 28-to-one, mostly in the form of regulations applied to businesses and localities. More pernicious are the dollars these agencies circulate — comprising a third or more of state budgets — which distort local priorities. The most destructive examples are federal programs that militarize local police forces and enlist them into our disastrous drug war, facilitated by the federally imposed legal doctrine of qualified immunity, which undercuts the rights of citizens against abusive government agents.

Other intrusions are more subtle. Federal agencies fund thousands of state employees in Wisconsin, for example, including nearly half its Department of Public Instruction. Many of those employees focus on compliance with federal grant requirements and, of course, securing more federal dollars — and the new state employees that will come with them. Other states’ budgets evidence a similar pattern. It’s a slow-motion invasion.

And where does it end? How does it end? So much rides on the ability of American communities to resist being sucked into tribal battles originating within our nation’s political class. All my mother knew to do in the face of it was to weep, and write letters, and love her neighbor. Maybe that all amounts to nothing. But maybe, if enough of us do it, it can be everything.