On Tuesday, Chicago voters head to the polls to vote for Rahm Emanuel’s successor as Da Mayor. ‘Why vote in late February?’ you might ask. ‘Didn’t Chicago just vote in November for House members and Governor?’

Oh, you naive soul. For decades, Chicago has held its elections in February precisely because it is cold, often snowy, and hard to get to the polls. When you suppress ordinary voters, who is left? For many years, it was reliable voters for the old Chicago Democratic Machine. Some of them drove city busses or garbage trucks; others shuffled papers in city offices. Some filled potholes. Many more watched their co-workers fill potholes while they grabbed a cigarette. What better way to ensure that insiders get reelected?

This system is on life-support, mortally wounded by the Federal Courts, which made two crucial rulings in the 1970s and 1980s. Known as the Shakman Decrees, the first said the city could not hire workers based on their politics. The second said it could not fire workers for the same reasons. The courts knew the city would not comply readily, so they appointed monitors, who stayed for decades.

Those decrees drove a stake through the heart of the old system, where alderman and ward committeemen gave out good-paying jobs to city workers who got out the vote. It was a well-organized system. The city employees had to visit homes in their neighborhood, listen to what residents wanted (such as a stop sign or better garbage pickup), and then share that information with their boss, known in Chicago as ‘their Clout.’ The visit concluded by reminding voters who they should vote for. Often the advice was simply ‘vote straight Democratic.’ These political workers were expected to make campaign donations and were held responsible for how many of their voters came to the polls. Fail in these critical tasks and find yourself a new job.

A few insurgents tried to buck the Machine, and the boys downtown had some tricks ready for them. One was to add a straw candidate with the same name as the insurgent. Another, which worked if the insurgent came from a different ethnic group from the Machine guy, was to add a straw candidate from the opponent’s ethnic, racial, or religious group. ‘Politics ain’t bean-bag,’ as Peter Finley Dunn observed more than a century ago.

It still ain’t, and some of these old techniques still work. But many new ones have been added. For privatized city services, for instance, the bidders need to understand who picks the winners and how to get on their good side. Take a guess: what percentage of airport vendors at O’Hare and Midway donate to the incumbent mayor and key aldermen? My guess would be 100 percent. I could be wrong. It might be 99 percent.

Local aldermen have another enduring source of leverage — and riches. Let’s say you need a zoning variation, perhaps to serve wine at your restaurant or build an apartment house. Your local alderman holds an effective veto over it. The rest of the City Council will respect his decision, just as he respects theirs.

‘Mr Alderman,’ you inquire, ‘isn’t there some way we can make this unpleasantness go away?’ Surprisingly, there is. Donate to his campaign. Give him your legal business. Buy insurance from his daughter. Better yet, do all three. When the son of Mayor Daley the Elder was caught in just such an insurance scandal, Da Mayor expressed his outrage at a press conference: ‘If a man can’t put his arms around his sons and help them, then what’s the world coming to?’

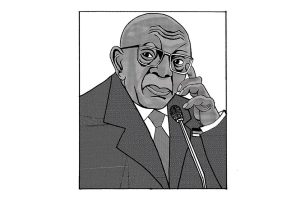

That eternal question must be plaguing today’s political insiders, who are facing a massive new scandal. The Feds have stepped up again, recorded Chicago pols’ most sensitive conversations, and tapped their phone calls. They even flipped the chairman of the City Council zoning committee, Danny Solis, and got him to wear a wire for two years. The growing scandal has now enveloped the most powerful alderman of all, Eddie Burke, longtime head of the finance committee. All his calls were tapped and his offices raided. He has been indicted for extortion. The remaining aldermen wait anxiously for more indictments, which are sure to come.

The Burke-Solis mess affects Tuesday’s city election, where 14 Democrats are running. Until recently, everyone expected Toni Preckwinkle to win, going away. She rose through the reform movement and now heads of the county government. She’s experienced, likable, and well-funded. But she also has an ‘Ed Burke problem.’ He held a very successful fundraiser for her. Not that there’s any connection, mind you, but she hired his son for a $100,000+ job and admitted she spoke to the elder Burke before making the hire.

Toni has strong backing from the AFSCME public-sector union and the Chicago Teachers Union, which is determined to squash the city’s large charter school program. While many voters still favor her, others worry about insider deals and whether she can tackle the city’s financial problems and continue its school reforms, which would pit her against her strongest supporters.

All the other candidates have limitations of their own. To put it bluntly, voters are still searching for someone who is

- Reasonably competent.

- Not too corrupt (we set achievable standards here in Chicago).

- Willing to tackle the city’s three biggest problem: city finances, crime, and the racial divide.

- Not hell-bent on raising taxes and killing growth (the same problem faced by the state of Illinois).

Unfortunately, no candidate meets all four criteria. Over a dozen candidates are running, and none meets all four.

So, voters have to figure out which criteria matter most. They also have to worry whether they might be wasting a vote on an outsider with little chance of winning.

A run-off is likely. That poses risks of its own, especially if it pits an African-American against a white candidate. Mobilizing those bases could easily compound racial tensions in a city where they are already strained.

Perhaps the most durable comment about the city’s politics came decades ago from Paddy Bauler, a city alderman and saloonkeeper. ‘Chicago,’ he said, ‘ain’t ready for reform.’

Tuesday could prove Paddy right again.