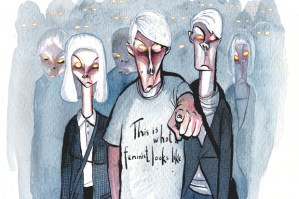

One of the depressing aspects of writing a column attuned to social hypocrisy is so rarely running short of new material. Any pundit keen to highlight the grievous injustices committed haughtily in the name of justice these days is spoilt for choice.

So: Augsburg University, Minneapolis, Minnesota. A student reads aloud a quote from James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time: ‘You can only be destroyed by believing that you really are what the white world calls a nigger.’ The last word causes a stir. When the white professor, Phillip Adamo, asks the class what they think of the student’s reciting of the quote verbatim, he repeats the word. The next day, the students kick Adamo out of his own classroom; since as ever the animals are running the zoo, he complies. The students powwow.

You know the drill: students complain to the administration about the ‘hurt’, ‘harm’ and threat to their ‘safety’ caused by having been subjected to a bad word. Cut to the chase: Adamo is removed from the course. He’s now been suspended for a second term.

Typically, all this wailing over trauma and injury is fake. The university campus is now a predatory environment, and the professors are prey. By allowing those two incendiary syllables out of his mouth, Adamo dangled a gotcha moment too enticing to pass up, as if having stopped to tie his shoelaces on a veldt teeming with hyenas. The pattern of these stories is unmistakable: they are not about justice, or the policing of prejudice. They are always about the exercise of power.

For it is not true that those poor Augsburg students are so stupid, so badly educated, so incapable of employing their own judgment, and so far removed from the world of common sense that they don’t know the difference between citation — during discussion of one of the most revered black authors in American literature — and the hurling of a historically loaded epithet with intent to wound. Of course they know the difference. In fact, it must have been the sheer unreasonableness of gleefully taking the professor’s teaching out of context that would have made this particular pedagogical safari so much fun.

I detest the expression ‘the N-word’. It’s a coy, prissy pantomime of purity, in an otherwise licentious era when we seldom even elude obscenity by substituting ‘the F-word’ any more. The pretense is that you’re not saying it, when of course you are. The dainty convention of ‘those syllables shall never pass these lips’ still calls up the slur (Louis C.K. once did a great riff on how the euphemism forces him to say the taboo in his head). The demure shorthand recalls the fastidious tradition — dropped by now, by most papers, but still pursued by the Telegraph — whereby readers are compelled to count the hyphens after ‘b’ to sort out whether the person being quoted said ‘bastard’ or ‘bitch’. Effectively, you’re still reading ‘bastard’ or ‘bitch’, right? Likewise, if anyone says ‘the N-word’ rather than the real thing, what do you hear?

To demonize the mere pronunciation of a racial epithet, regardless of context, is superstitious. Caucasians’ clunky, terrified avoidance of this pejorative above all others ascribes mystical powers to the word, and if anything helps to maintain its sting. Why, the pandering practice ascribes mystical powers to white people themselves, as if some pale face daring to speak the incantation aloud will summon the grisly specter of Hendrik Verwoerd and issue in a generation of worldwide apartheid.

Especially when otherwise quoting black artists word-for-word, the showy avoidance elevates derogatory names for black people as more wicked than all other slanders, like ugly names for Pakistanis or Jews. Are we really to accept that some racial prejudices are way worse than others? Why don’t they all suck? Even the four-letter ‘C-word’ has made a comeback spelled out, whereas ‘the P-word’ and ‘the K-word’ aren’t even set expressions, and if you adopt those elisions you’re apt merely to befuddle people. No, at this point there’s only one word that white people absolutely must not speak.

So in December Ricky Gervais was even given grief for saying you-know-what in the process of explaining why in comedy routines he doesn’t use it. Meanwhile, the authentic ‘N-word’ sprinkles rap and hip-hop lyrics like confetti. White folks can’t help but feel — privately — a little taunted. So white lecturers who teach whole courses on this music are frightened of reading aloud the very lyrics they’re analyzing, while white fans had better think twice before singing along on the Tube. Fair enough, the co-opting and refurbishment of pejoratives has form. The ‘Q’ in LGBTQ, ‘queer’, has been repurposed into a badge of self-respect. But fair play to the pride movement: now everybody gets to use it.

As for the supreme no-no, the crackers can’t even get close. In 1999, a mayoral aide in DC was shamed into resigning after describing a budget item as ‘-niggardly’ because some ignoramus didn’t know what the word meant. Right-on whites are thus anxious about visiting Niger, ordering a negroni, niggling over a bill or sniggering at a joke, assuming anyone in the surround of the vauntingly virtuous ever makes one. If white folks recommend the 2002 book Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word, presumably they’re obliged to abridge the title; Amazon’s algorithm won’t recognize the embarrassed abbreviation, and the distinguished author, black Harvard professor Randall Kennedy, misses out on sales.

Outside this very column (which only spells out the ‘troublesome word’ in quotations of black American notables; let’s not tempt fate), I’ve little need to invoke this supernaturally potent term, so the taboo doesn’t cramp my style. And obviously — I shouldn’t have to add this — all racial slurs, when used as abuse, are poisonous. But we can all distinguish invective (shouting directly at an Irishman, ‘You dumb mick!’) from reference or reportage (‘That unpleasant person just called an Irish gentleman “a dumb mick” ’), even though both include the slur. Phillip Adamo’s crucifixion by his students for discussing James Baldwin was an act of disingenuous mercenary opportunism. In other words: the usual.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.