Most everyone outside the Biden administration knows that a recession is now more than likely. We could be entering what economist Noriel Roubini describes as the “Great Stagflation: an era of high inflation, low growth, high debt and the potential for severe recessions.” Certainly, weak growth numbers, declining rates of labor participation and productivity rates falling at the fastest rate in a half century are not harbingers of happy times.

But the coming downturn could prove a boon overall, if we make the choices that restore competition and bring production back to the United States and the West. The contours of a new post-pandemic economy are becoming clear, particularly in the Sun Belt and parts of the heartland. That revival could leave us with an economy that is stronger, more innovative and entrepreneurial.

This is not to say that a recession won’t be hard, particularly for groups like millennials, blue-collar workers and immigrants who have already suffered through the 2008 recession as well as the pandemic. They have been victims of very poor business and government practices that have created inflation and incentives either not to work or to invest in nonproductive activities. But if the 2008 recession ended with only tepid growth, this time around we may eventually see something different.

The best evidence for the prospect of better times lies in the post-pandemic increases in new business formations, in 2020 up to 4.4 million applications compared to roughly 3.5 million in 2019. In the first half of 2022, applications including those from non-employer businesses remained up by 44 percent from before the pandemic. In 2021, applications, including likely employer applications, totaled around 1.8 million by year’s end — almost half a million more than in 2019. According to the Economic Innovation Group, US new-business starts are on course to set a record this year.

The action today, unlike that of the previous decade, is not found so much among finance-backed IPOs, which are suffering their biggest decline in two decades. Instead, small grassroots businesses are seizing new niches, even in service industries, that could transform our economy. “Lots of good things happened during Covid,” suggests Shaheen Sadeghi, founder of California-based LAB Holdings, which builds “anti-malls” hosting local businesses. “The mediocrities went under, but the people who survived are doing better than ever before. They created new ways of doing business that fit the new realities.”

This grassroots growth is very different from what happened after the last serious recession in 2008. Once the financial engineers of the City and Wall Street finished demolishing the economy, governments moved to bless more consolidation.

The big banks recovered gloriously as inequality soared and incomes, particularly for minorities like African Americans, sank. As one conservative economist put it in 2018, “The economic legacy of the last decade is excessive corporate consolidation and a massive transfer of wealth to the top 1 percent from the middle class.” Fortunately, entrepreneurialism remains embedded in our national DNA. In more managed societies — like Germany, Japan or France — the leading companies tend to remain the same over time; even those historically connected to fascism, such as Mercedes, Krupp and Mitsubishi, survived their ignominy and remain dominant. But in the United States disruptive change has been the norm: only fifty-three of the current Fortune 500 companies were here in 1955.

This emerging new economy is also reshaping our economic geography. Sadeghi’s LAB (“Little American Business”) has developed nearly fifty projects for small, independent firms, predominantly in suburban settings, places not usually thought of as sources of cultural and business innovation. By contrast, the massive bailouts standard for the last three years have not slowed the movement of people and companies away from dense, often hyperprogressive urban locales, dispersing people and work to their periphery.

This is a marked change from the last recession. The great financial crisis of 2008, precipitated by the bursting of a housing bubble, led to much speculation that Sun Belt suburbia would become what the Atlantic predicted would be “the next slums,” and that city living would make a comeback. To be sure, the oligarchic nature of the recovery was somewhat less damaging to cities like New York, San Francisco and Boston, where financial and tech firms are concentrated and key managerial talent remained, despite its previous malfeasance.

Yet the ongoing exodus from big urban centers started before Covid, with over 90 percent of all metropolitan growth between 2010 and 2020 in the suburbs and exurbs. The 2020 census notes that four of the five US counties gaining at least 300,000 people were in Texas, Arizona or Nevada. Houston and Dallas added far more people than New York, Chicago, Los Angeles or the Bay Area.

The pandemic, and the rise of online work, seem likely to accelerate this movement. The big blue coastal cities have all experienced meager growth and, since 2020, serious population losses. In the last year, the biggest migration losses took place in three key states: New York, New Jersey and Illinois. In the post-pandemic economy where some 30 percent of the employed expect to work mostly remotely, this turns even small towns into new centers of economic dynamism.

Overall, notes demographer Wendell Cox, offices on the fringe have recovered far faster than those in the largest urban cores. According to Jay Gardner, president of Site Selectors Guild, leading companies are looking increasingly at opportunities in smaller cities and even rural locations. The biggest upsurge in new business formation took place in the Deep South, Texas and the southwest while New York and the West Coast lagged. This year, Zen Business found that the best places for small businesses — in terms of taxes, survivability and regulation — were overwhelmingly in the south, parts of the Great Plains, Utah and the Midwest.

One surprising aspect of the emerging economy reflects tentative steps by corporations to return production to the United States. The “reshoring” movement has been building over the last several years, helped by the boom in shale oil and gas, which makes US manufacturing more efficient. But the return became imperative when China blocked healthcare exports during the worst days of the pandemic. Our painful dependence — even for military goods — on our primary global adversary is starting to concentrate minds.

Indeed, up to 70 percent of firms consulted in a March 2020 survey said they were likely or extremely likely to reshore in the coming years. Camille Farhat, CEO of RTI Surgical, suggests the pandemic is convincing business leaders to stop “destroying the supply ecosystem” that makes production possible. “To stay safe, you have to do contingency planning. You have to restore the network and maintain surplus production capacity. Hopefully, we are learning that lesson.”

Returning production to the United States opens new possibilities for more than manufacturing. When firms move production abroad, they often follow by shifting research and development there as well. Now the United States, and the West generally, have a chance not only to relearn the basics of production but to hone and maintain their innovative edge. Critically, there is widespread political agreement on this issue, outside of some libertarian fundamentalists and a few congenital socialists.

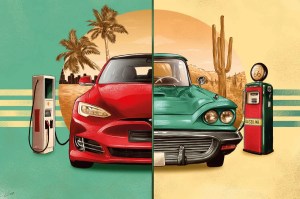

The return of production will only enhance the current geographic shift already underway. The new investment tide is far more likely to head to business-friendly, lower-cost states than to those like California, which ranked near the bottom of the table last year for new capital projects. Critically the new surge of chip production — backed by the federal government and once the pride of my state — is occurring almost entirely in more flexible states like Ohio, soon to be the site of the world’s largest semiconductor factory. Even the green economy, so passionately embraced on the blue coasts, won’t provide many jobs there. Almost all the new electric vehicle and battery plants are located in the heartland, the south or locations east of the Sierra Nevada. Tesla’s original California plant may soon be the only large-scale “green” factory left in the state.

This new wave of industrial development could be transformative, bringing new wealth and opportunities to left-behind areas. Manufacturing industries attract skilled workers such as engineers and software developers, as well as training and development for the local work force. States like Ohio, Kentucky, Nebraska and Tennessee already have flexible training programs following the successful approaches employed in such places as Germany, Sweden and Denmark.

Of course, even the threat of a recession, much less a strong one, is likely to cause widespread pain. Whether or not that pain is mitigated by new opportunities depends on whether cities, states and the federal government adopt policies that allow Americans’ natural proclivities to thrive. Orneriness and individualism — sometimes manifest as determination and perseverance — may not currently be popular with the governing classes, but ambitious restlessness could well prove the best response to disruptive times.

This would necessitate, particularly in our great core cities, a turn away from a focus on “inclusion” and environmental righteousness to a regulatory regime that encourages new locally centered growth. This would include ditching policies like rules banning contract work or artificially high minimum wages that suppress start-up growth. Rather than focus only on pleasing large enterprises, and their investors, states and cities need to regard start-ups and fledgling businesses as critical seedcorn for their own future.

As the downturn worsens, there will be calls to extend the welfare state along Scandinavian lines, comforting for some but unlikely to create a strong post-recession America capable of leading the world economy or competing with China. Nor do we need to go back to the ruinous consolidation of financial assets that help fund chimeras like WeWork and their performative hypesters, which produce very little real value.

The real heroes of post-pandemic America won’t be the oligarchs, flashy venture-funded promoters or the elite bureaucrats who lorded it over the nation during the pandemic and seek to repeat the performance under the aegis of “climate emergency.” Rather than imperious bureaucrats and craven corporate executives, our future economy depends on those who rent a deserted storefront on Main Street, establish a business from home, or build a new production facility in rural settings or exurbs. Most will never be celebrated in the press but collectively they represent the hidden power that can move America back toward a dynamic democratic capitalism that the world, particularly the next generation, desperately needs.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2022 World edition.