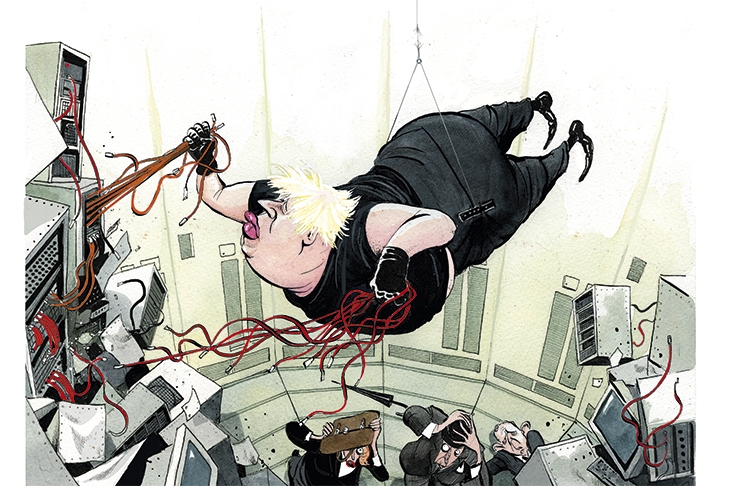

It’s never a good sign when a government relaunches itself. Look what happened at the end of Theresa May’s time in power — there was a relaunch almost every other week, each one with diminishing effect. But although it has been over-hyped, Boris Johnson’s attempt to start again isn’t a mere re-branding exercise. It is not just about rehashing policy proposals but about trying to tackle the dysfunction at the heart of the state. The PM is attempting to do something past leaders have thought to be an impossible job: to rewire the whole system.

Johnson has time on his side — four years to get things back on track — and a Commons majority. But there’s a paradox at the heart of this big reform project: if he’s so frank, almost brutal, about the failings of government, how can he be pinning his hopes on government to solve the UK’s economic problems?

In normal circumstances, a politician’s view of the efficiency of government informs their view on the role of the state. The post-war Labour government was animated by the belief that ‘the man in Whitehall knows best’, and so the state became ever more involved in both the economy and in people’s every-day lives. Margaret Thatcher thought individuals were better judges of their own needs than government, and set about rolling back the frontiers of the state. This No. 10 thinks that the British administrative state is deeply flawed, dysfunctional even, but nevertheless it is relying on government, of a reformed kind, to deliver the changes it believes are crucial to this country’s future prosperity.

If Michael Gove thinks the civil service is so out of sympathy with the majority of the country, then why isn’t he proposing to cut this flawed Leviathan down to size? The Thatcher/Reagan approach would seem to be a more logical reaction to the failings of government. But it is worth remembering that when Reagan declared in his first inaugural that government was the problem, not the solution, he caveated it with the phrase ‘in this crisis’. Reagan was still an admirer of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal. It was a reminder that circumstances matter in politics; and in the current situation, government has to be a significant part of the solution. The problems Britain faces today are a far cry from those of the 1980s. One ally of the Prime Minister sums up the mood as: ‘The machine is dead, let us build a new machine and advance.’

Even before COVID, the UK was in a productivity crisis and it’s nigh-on impossible to improve productivity without government involvement. Increasing productivity requires improvements to be made to physical and digital infrastructure and to the skill base, and those need public investment.

One of the reasons Johnson is so keen on big infrastructure projects is that he thinks this is one area where the public sector doesn’t crowd out the private sector. But he has to stop allowing such projects to waste so much time and money.

Can he succeed? His is not the first government to attempt to reform Whitehall. For two generations, British politicians have been trying to make the administrative state function better — and with little success. Some ministers regard it as a distraction from the issues that the government should be focusing on. One observes that ‘it is always easier to blame things on structures’ than to solve problems with policy. Veterans of the Cameron government are beginning to chuckle with schadenfreude: they regarded Whitehall reform as the ultimate rabbit hole for any prime minister to go down. And yet it remains true that nothing significant can change until the machine of government functions properly — and if the COVID crisis has made one thing clear, it is that it currently does not.

Johnson and his circle believe that reforming Whitehall is ‘existential’ to this government’s prospects. One Tory tells me ‘sorting out the state isn’t an esoteric thing but key to delivering on the things that will keep our seats’. Their fear is that without a state that can deliver, they will be swept out of office in 2024 by the appeal of a ‘time for a change’ after 14 years of Tory rule.

So what will a rewired government look like? At the heart of the project are changes to the cabinet office. The departure of Sir Mark Sedwill as cabinet secretary and national security adviser is just the start. There will be limits to this revolution: Sedwill’s replacement will be a current or former permanent secretary; the first civil service commissioner Ian Watmore insisted on that. But this bar on bringing in an outsider matters less, because the role of the cabinet secretary is about to change significantly. In the new disposition, the cabinet secretary’s most important role will be as head of the civil service.

No. 10 have no chosen candidate, so this will be a genuine competition. But some permanent secretaries are not in serious contention: No. 10 think that the institutional response of the Department of Health and Social Care to this crisis has been deeply flawed, so that perhaps rules out Chris Wormald at the Department of Health. Antonia Romeo, the permanent secretary at the Department for International Trade, is another much-tipped name who is unlikely to get the job. There is no requirement for the next cabinet secretary to be a Brexiteer, but interestingly the view in Whitehall is that of the 40 or so permanent secretaries, only one voted for Leave and perhaps two more are Brexit-curious.

The new No. 10 permanent secretary Simon Case, who is highly regarded, will take on an expanded role in this new system. I understand that the domestic policy secretariat, which resolves disputes between government departments, will report to him. This team will have embedded in it something akin to Tony Blair’s delivery unit. Its role will be to chase policy across Whitehall, ensuring that there is follow-through on the government’s commitments. At the same time, the national security secretariat will report to David Frost, the Prime Minister’s chief Brexit negotiator, who is the new national security adviser. This set-up will be in place by the autumn.

Cynics say that reforming Whitehall has been attempted before, and that it always fails. There is a reason to think that this time might be different: COVID. The virus has been a test of governments, and systems of government, around the world. No one can look at the UK death toll and conclude that this must be one of the best-governed countries in the world. It is clear that in terms of public administration we lag behind Germany, and far behind the Asian democracies. This realization means that the forces of reform in Whitehall have been strengthened and the forces of conservatism weakened. As one secretary of state puts it: ‘Crises provide an opportunity to upend some of the things that haven’t worked in the past.’ And the secret spur pushing on the reform agenda is the inevitable public inquiry into the government’s handling of COVID. There will be plenty of criticisms to make. But the machinery of government is bound to come in for heavy fire, strengthening the case for change.

Ministers now accept that the state really does need reforming — that it has failed its stress test. One of those intimately involved in the government’s coronavirus response tells me: ‘People have been astonished at how rotten much of the British state is. Every time you look close up to check that part of it is functioning OK, you find disaster. It’s like leaning on what seems to be a solid wall and finding it’s rotten: your hand pushes straight through.’ Johnson has been radicalized by the experience. I am told that ‘he is much more interested in reforming the civil service than he was pre-March’.

Perhaps more important than the effect this crisis has had on ministers is that it has strengthened the view of the cadre of Whitehall high-flyers that change is needed, that the civil service can’t just go on congratulating itself on being a Rolls-Royce machine. This is why 41-year-old Case is such an important figure in this Whitehall revamp. One admirer of his says he ‘represents a younger generation who understand that things have gone awry’. This younger generation is important, because no changes to Whitehall are going to work unless there are civil servants who agree that they are necessary. Reform is not something that can simply be imposed by ministerial diktat.

Even more important than the shift in structures is the shift in mindset intended to accompany it. A more rigorous examination is required of whether government policies have delivered returns on money put into them. The government aims to make data publicly available in order to enable faster course correction — but it is far from achieving this. Take Leicester: the coronavirus testing data that is the basis for locking down the city is not open to external examination.

The new emphasis on data must properly distinguish between data and modeling. Data has real analytical value — it enables robust discussion of what has worked and what has not. Modeling is a far less exact science. In this crisis, as in the 2008 financial crisis, models have been more of a hindrance than a help.

[special_offer]

Curing Britain’s ills requires an effective government, but it will also take a realistic idea of what government can do: the failure of the test-and-trace app is a reminder that government technology projects can sound great but be deeply flawed in practice. The emphasis should be on allowing government to get on with doing the things it is best suited to: building infrastructure, taking care of public health, and ensuring access to education and skills training.

There’s a danger that this desire to use the state will lapse back into tired thinking. There is something depressing about the emphasis Johnson is putting on new school buildings in the north and the Midlands. If the British government thinks that one of the biggest problems with education in England is the quality of the school estate, then it really is out of ideas. Leveling up has to mean more than just building new schools and hospitals in deprived places.

Relying on the effectiveness of government is an uncomfortable place for any center-right administration to be. But this is where Boris Johnson’s Conservatives find themselves. His future is dependent on his ability to make government work better.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.