Donald Trump secured his third choice for his third Chief of Staff on Friday.

Though the budget pointman, Mick Mulvaney, has only been tapped for the top job in an ‘acting’ capacity – implying a probationary period – there’s every reason to think Mulvaney could prove a success.

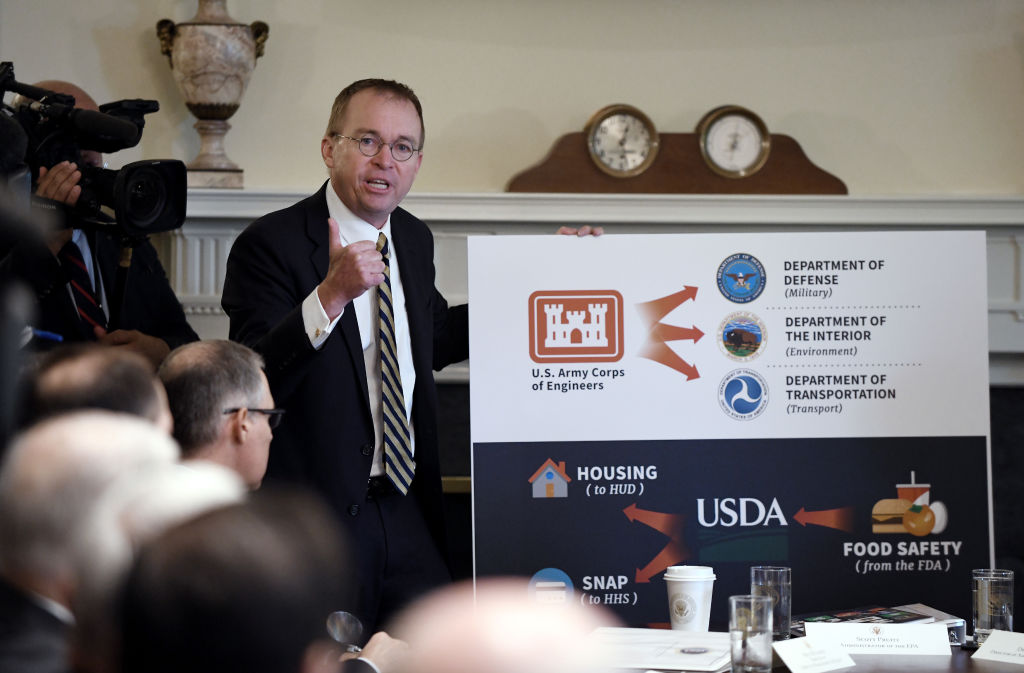

Mulvaney, a former Congressman from South Carolina, has proved indispensable for Trump in his early years in office, taking jobs that the president has struggled to fill. While the latest is chief of staff, Mulvaney also temporarily headed the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau from late last year into 2018.

But some hope Mulvaney secures his latest job for the long haul. Spurned by Nick Ayers and Chris Christie, Trump has an incentive to show stability. And as he faces legal blockades and Congressional rebukes, Mulvaney might just prove to be the man for this season.

He could help Trump harness his inner foreign policy restrainer. Unlike the president’s mostly hawkish slate of past appointees, Mulvaney actually agrees with Trump on the broad strokes of reducing an overstretched America’s military footprint in the world.

Mulvaney embodies what one could argue is the paradox of Trumpland support: that Republicans draw heavily on the military, which drives the American Right away from primacy. Mulvaney, who represented a House district laden with military interests, noted in 2013 when the nation weighed against Bashar al-Assad’s Syria that ‘to say it’s 99 percent against would be overstating the support.’ His analysis would presage Trump’s rise, solidified in in particular by the 2016 South Carolina primary debate performance in which Trump lambasted his foe Jeb Bush for his brother’s ruinous incursion into Iraq.

The libertarian-leaning Mulvaney is worrisome to other elements of the president’s base – particularly immigration and trade hawks. But chief of staff is not a policy job. Rahm Emanuel, Barack Obama’s inaugural chief of staff, famously disagreed with the 44th president’s decision to center his presidency on healthcare (a legislative achievement now all but nullified by Trump). Mulvaney is unlikely to change the administration’s course on either trade or immigration. Where he can make waves is on an area the regime has lagged: personnel. Friendly with the Freedom Caucus and allies of Rand Paul, he could secure foreign policy fellow travelers something they’ve long sought and largely been denied since the White House departure of, primarily, Steve Bannon: an audience with the president.