Not all pro-lifers are happy with the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade. In a column at the Washington Post, former George W. Bush speechwriter Michael Gerson acknowledges that Roe was “poorly argued,” but says he is “more comfortable with the gradualism” recommended by Chief Justice John Roberts. Gerson ends even more soberly: “The abortion debate — with all its tragic complexities — has been returned to the realm of democracy. And there is little evidence our democracy is prepared for it.” Why? Because the “GOP has become captive to an ideology of power.”

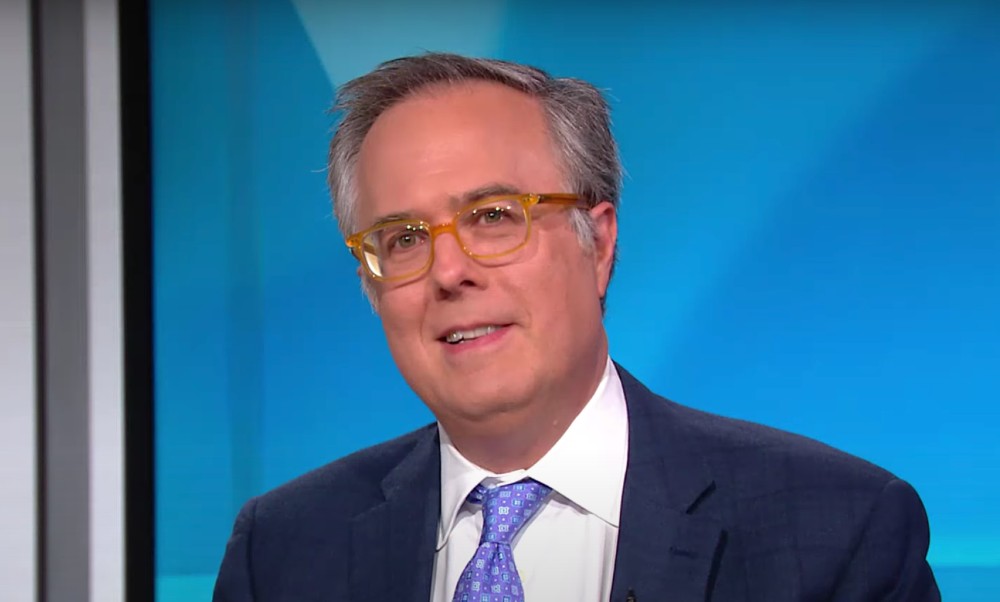

Anyone who has been following Gerson over the years will not be surprised by these comments. The Wheaton-educated evangelical has been repudiating his former friends on the right, particularly over their support for former President Trump, whom Gerson has spent more than half a decade relentlessly attacking. The Bush speechwriter who gave the right such phrases as “the soft bigotry of low expectations,” “axis of evil,” and “compassionate conservatism” is now decidedly on the left.

And not just any left. In a June column celebrating Pride Month, Gerson praised the LGBTQ+ movement for its “compelling view of human dignity,” and criticized its detractors for uttering words that “must feel intolerant while emerging from their mouths.” In the same piece, he plays the biblical exegete, asking, “Why should we assess homosexuality according to Old Testament law that also advocates the stoning of children who disobey their parents?” He argues that St. Paul’s words on homosexuality are culturally conditioned, while Jesus never mentioned it. Thus, Gerson says, “I’m up for some Pride bocce” (Pride bocce balls are apparently for sale at Target).

Though presumably still an evangelical, Gerson also has lots to say about Catholicism. In another June column, he praised Pope Francis for reining in traditionalist Catholics and their Latin Masses, which he says are a “parallel form of Catholicism.” He commends Francis for “continuing his slow exposure of the Catholic Church to some of the better aspects and instincts of modernity, including the marriage of priests, an expanded role for women and a warmer welcome of LGBTQ Christians.” And he lauds Francis’s support of the Jesuit LGBTQ+ advocate Father James Martin.

Gerson these days evinces a particular manifestation of the left with more than a century of pedigree: liberal Protestantism. That moniker does not mean simply Protestants who are politically liberal, but a specific brand of Protestant Christianity that rose in prominence in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was a Christianity that sought to reconcile the faith with modernity, whether that be scientism, materialism, or utilitarianism. In with the enlightened doctrines of progress, out with arcane, ignorant doctrines of traditionalism. Or, as J. Gresham Machen writes in Christianity and Liberalism (1923), “Christianity is founded upon the Bible…. Liberalism on the other hand is founded upon the shifting emotions of sinful men.”

As Gerson’s politics have shifted leftward, so has his Christianity. Traditional Christian teaching on sexuality and gender has been scrapped in favor of new, fresh readings…though truthfully not all that fresh. Liberalism’s origins are traceable at least to the German theologian Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher, born in 1768.

Any theological system premised on progress and innovation is always in search of totems to topple. Just look at what liberal Protestant scholars care about — it is all apiece with the broader racial and sexual fetishes of the left. God, they say, is a black woman and Jesus was intersex. Down with racist and patriarchal ecclesial institutions! Princeton Theological Seminary is committed to “antiracist formation”; Harvard Theological Seminary teaches “ecotheology”; Chicago Theological Seminary offers a “Certificate in Theological Studies with an LGBTQ Concentration.”

It’s all very predictable. Whatever the current obsessions of the broader secular culture, one will find them in the academic research and novel doctrines of liberal Protestantism. Rather than Christians being the “salt of the earth,” they become indistinguishable from, and subject to, the temporal and profane. Whether motivated by a misguided desire to be in the world or simply moral cowardice, the result is ultimately submission to the pagan gods of postmodernity.

I still like the slogans “compassionate conservatism” and the “bigotry of low expectations.” They are pithy, effective phrases. In our post-Roe world, conservatives must prove the left wrong and be devotedly compassionate to the most vulnerable women and children in our communities. And many of our economic and academic policies do reveal a certain bigotry towards the disenfranchised, whom, our elites tell us, require special coddling. A public elementary school near my Virginia home, for example, gives troublesome students extra recess time to help them cool down.

Surely Gerson’s capitulation to predictable liberal canards was not inevitable — when Trump’s political star first rose, many other thoughtful conservatives were skeptical, if not even at times disgusted. Yet over time, Gerson’s understandable distaste for the extremes of Trumpian populism turned into condescension for the kinds of people “compassionate conservatism” was intended to elevate. And the more Gerson found common cause with the left, the more he started to think and act like them. He began carelessly caricaturing those he censured, and losing the self-awareness to realize he had assumed a bit part — the “principled” anti-Trump white evangelical — in a broader messaging campaign. He became, like so many other neoconservatives, an exploitable patsy for elite leftists trying to preserve a patina of “objectivity.”

It’s an ironic, sad story of surrender. Ironic, because a man whose criticism of conservatives originated from principles he has now abandoned in favor of woke progressivism. Sad because he thinks it’s his opponents, not him, who have been made captive by “an ideology of power.”