Boston

Elizabeth Warren has all the answers, a plan for every disaster and the hectoring manner of a professor whose class are dozing off after lunch. Unfortunately, the voters don’t believe any of it.

‘I’m in this race because I believe I will make the best president of the United States of America,’ Warren insisted at a rally in Detroit, Michigan on the afternoon of Super Tuesday. Meanwhile the voters of Massachusetts went to the polls and disagreed.

How could Warren have seriously believed this? She’d already been immolated in Iowa, handily neutralized in New Hampshire and sourly creamed in South Carolina. Bernie Sanders was always going to win Vermont, but the Vermont exit polls showed Warren being beaten into fourth place and single figures by Michael Bloomberg. It was little better in Maine, where exit polls had Warren only just reaching third place and double figures. Warren might not have expected to take Oklahoma, the state of her birth, but she must have hoped to do better than to be beaten by Bloomberg into fourth place. She was adamant, however, that she’d win in her home state of Massachusetts, where the exit polls put her in third place, behind Sanders and Biden. MSNBC declared Biden the winner in Massachusetts at around 11p.m., ET. Why was Liz so confident?

Massachusetts is famed for its predominance of Independent voters. In 2018, as many as a third of them expressed their independence by voting for a liberal Republican, Charlie Baker, as governor, and Warren as a senator. While Super Tuesday’s exit polls had called Virginia for Joe Biden and Vermont for Bernie Sanders even before the voters had gone in, the empurpled electors of Massachusetts had long reached their verdict on Warren — two years ago, in fact.

Warren won her 2018 Senate campaign by sweeping the board in the metro Boston area and liberal western Massachusetts. She took 92 percent of the black vote too. But a WBUR exit poll found that though Warren won over 60 percent of the votes, only 36 percent of those surveyed thought she would make a good President. Nevertheless, she persisted.

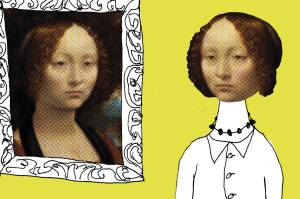

The ambivalence in that 2018 poll has recurred in this campaign. There are two Elizabeth Warrens. One a technocratic centrist who has profited personally and professionally from the consensus, apparently by inflating her Cherokee ancestry. The other is a left-wing redistributionist who wants to break up the banks and monopolies. The first of these candidates appeals as a more cogent Joe Biden, the second as a less lunatic Bernie Sanders. But does either of them convince?

The link between these two Warrens is her wonkish conviction that people are problems to be fixed by legislation. This is traditional progressivism, and it should go down well in the Kennedy State. Warren’s problem is one of class. This is unfair on her, in a way. As an oleaginously sympathetic New York Times article explained on Tuesday — a slightly premature obituary, really, for a campaign that was clearly dead on its feet — Warren grew up on what she calls ‘the ragged edge of the middle class’ in Oklahoma. Her father died when she was 12, and she raised herself by the sartorial acrobatics that the Times calls ‘up-from-the-bootstraps’.

But, just as she was known as ‘Betsy’ then and is now ‘Elizabeth’, Warren has pulled herself and her bootstraps up so successfully that she seems to be all professor and no plebeian. And, as the Times delicately hinted, she couldn’t make too much of her ascent to Harvard Law because that would revive the whole ‘Pocahontas’ business:

‘Ms Warren has long since graduated from her childhood economic insecurity to life with a golden retriever, Harvard tenure and a Senate sinecure. Her decision to undertake a DNA test in late 2018 to show Native American heritage haunted her candidacy in its early months, and could have complicated efforts to focus on the rest of her family story, however evocative.’

Apart from sounding as though the retriever was given to her by Harvard Law — like a golden handshake, but with free dog food — this account entirely avoids the word ‘Cherokee’. Nor does it mention that the DNA test she took in 2018 ‘to show Native American heritage’ didn’t show much of it all, and that a few months later she evocatively apologized to a leader of the Cherokee Nation for taking the test.

The silence, as the Cherokee say, speaks volumes. Even Warren’s supporters know that her candidacy was compromised by having appeared to exploit affirmative action. Warren the radical promised to break up oligarchies and monopolies, but Warren the technocrat appeared to have excelled at pleasing the oligarchic and monopolistic attitudes that control access to the spoils and golden retrievers of higher education. Too well, perhaps: she was the candidate of the professoriat, and though there are lots of professors in Boston, there aren’t enough to win a primary.

Instead, Warren will hang in, spend some more money and hope for a contested convention, where centrist Warren can be Joe Biden’s running mate or radical Warren can be Bernie Sanders’s. Like she always says, she’s a politician of principle – the principle being that she knows what’s best for everyone else and therefore has a right to impose it on us.

Dominic Green is Life & Arts editor of Spectator USA.