I first met Ken Starr in 1989. I was a Wall Street Journal editorial writer who was invited to speak at a conference held by the Federalist Society’s chapter at Cornell University.

I met two very impressive people that day. One was Leonard Leo, the head of the Cornell Federalist Society. Only twenty-four, it was clear he had a natural genius for organizing, planning and networking. As the later head of the Federalist Society, he turned it into the premier farm team for conservative lawyers who wanted to become judges. In 2020, then-CNN legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin told a group of lawyers that Leo had played a major role in the selection of a majority of the Supreme Court.

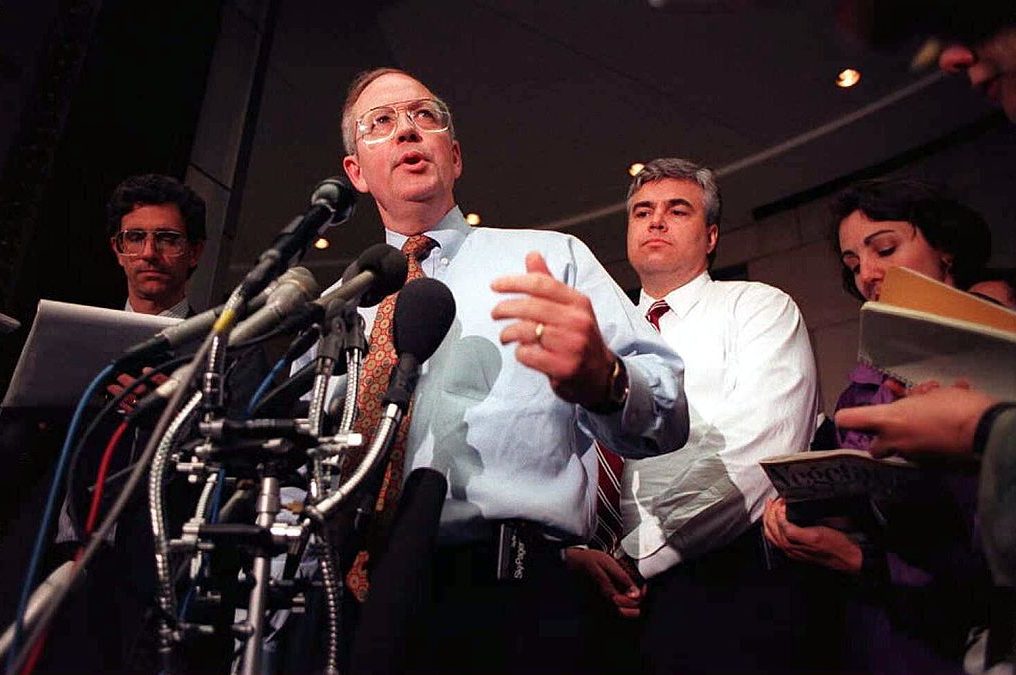

Also at Cornell that day was Starr, who was then a judge to the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, the second most important court in the country and one viewed as a stepping-stone to the Supreme Court. Before the Federalist Society was even launched in the early 1980s, Starr was already seen as a potential nominee to the nation’s highest court.

When I met him, he had served as a top legal advisor in the Department of Justice, become the youngest person ever appointed to the DC Circuit and had just been appointed by President George H.W. Bush as US Solicitor General, the official who argued the government’s cases before the Supreme Court. A brilliant legal mind, he dazzled the conference’s audience with his keen analysis and dry wit.

Everything appeared to be going Ken Starr’s way in the early 1990s until he had a rendezvous with Whitewater in 1994. Whitewater was a rancid Arkansas real estate deal in which then-governor Bill Clinton and his wife Hillary had been financial partners with their friends Jim and Susan McDougal. After the suicide of White House deputy counsel Vincent Foster shortly after Clinton became president, Foster’s role as a private lawyer for the Clintons became the subject of great scrutiny. Under pressure, President Clinton agreed to have Janet Reno — his attorney general — appoint an independent counsel to look into Whitewater because of the conflict of interest.

A panel of federal appeals court judges replaced Reno’s choice in August 1994 due to irregularities in Reno’s original decision making process. Their choice was Ken Starr.

Starr set up a crack team of prosecutors and investigators that plowed through the ethically murky soil of Clinton’s Arkansas. They hit pay dirt.

The McDougals were convicted for their role in the Whitewater project. Jim Guy Tucker, Bill Clinton’s successor as governor, was convicted of fraud and replaced by a then unknown GOP lieutenant governor named Mike Huckabee. Webster Hubbell, a close friend of the Clintons who was their handpicked choice to be the No. 2 official at the Justice Department, was convicted of fraud and sentenced to twenty-one months in prison.

But by late 1997, the stonewalling of key witnesses left Starr unable to secure evidence directly linking the Clintons to the Whitewater matter or other scandals such as the improper obtaining of FBI personnel files by the White House.

It looked like he would have to wind down his probe — and he began talks with Pepperdine University to head their law school.

But then the Supreme Court unanimously gave a green light for sexual harassment allegations by Paula Jones against Clinton to go to trial. In January 1998, Clinton testified falsely about the Paula Jones case before a federal judge and his affair with former White House intern Monica Lewinsky became public. Allegations that Clinton had sought to cover up the Lewinsky affair prompted Attorney General Reno to expand Starr’s mandate.

The rest of the story, you could say, was as much hysteria as it was history. Former federal prosecutor Andrew C. McCarthy calls Starr’s role in the Lewinsky probe “the most thankless task in modern American history.” He recalls that Democrats and their media allies united in trying to protect Clinton and “spared no effort to destroy” Starr.

Keith Olbermann of MSNBC dubbed him a Nazi who looked like Heinrich Himmler. Geraldo Rivera, then of CNBC, mocked him with a bizarre nursery rhyme: “Twinkle, twinkle little Starr, now we see how wrong you are. When you drag the agents in, when you bully moms and kin….” Al Hunt, Washington editor of the Wall Street Journal, accused Starr of “pandering to Clinton-haters” and appearing to be “a political hit man.” Hillary Clinton said Starr was at the center of “a vast right-wing conspiracy.”

But Starr soldiered on, and in September 1998 he filed a 400-page-report, as the law required, with Congress. He concluded that Clinton lied under oath, engaged in obstruction of justice and attempted to silence witnesses.

But the focus of the attention given to the Starr Report quickly became the unusually lurid and erotic details about Lewinsky’s affair with Clinton that were included. Starr was shocked when Republican congressional leaders released the entire report on the internet without even reading it.

He was quickly attacked as a Puritan witch hunter obsessed with invading private lives. A Queens real estate developer named Donald Trump mocked him as “a total wacko” and “totally off his rocker.” (Starr would years later in 2020 defend President Trump during his first impeachment trial by arguing the charges of Ukrainian collusion did not rise to “high crimes and misdemeanors.”)

The first impeachment trial of a president in 130 years resulted in Clinton’s acquittal. But Clinton was forced to settle out of court with Paula Jones for $850,000 and Starr’s successor as independent counsel extracted an agreement from Clinton which involved him paying a fine and surrendering his law license for lying under oath.

Starr finally accepted a delayed offer by Pepperdine University’s law school to become its dean. In 2010 he became president of Baylor University, but was demoted in 2016 after an investigation found that the university had mishandled accusations of sexual assault against members of the football team. At the time, Starr said, “I didn’t know about what was happening, but I have to and I willingly do accept responsibility. The captain goes down with the ship.” How un-Clintonian.

After his Baylor service, Starr continued to argue cases before the Supreme Court in high-profile matters. He made it his mission to promote the expansion of religious freedom in the courts. He joined the board of directors of the Global Justice Foundation, a watchdog group founded by Canadian businessman Omar Ayesh to expose the corruption of courts in developing countries.

In his memoir, Contempt, published in 2018, Starr questioned how he wound up pursuing Clinton’s affair with Lewinsky. But he insisted that the former president’s perjury and trashing of the Rule of Law couldn’t be ignored.

“I deeply regret that I took on the Lewinsky phase of the investigation,” he wrote. “But at the same time, as I still see it twenty years later, there was no practical alternative to my doing so.”

By taking on the Whitewater independent counsel role at age forty-eight, Ken Starr effectively ended any chance of the Supreme Court appointment he and so many of his friends felt he deserved.

But in one of life’s career ironies, Starr was present in 2018 at the swearing-in-ceremony of a good friend who took a seat on the Supreme Court. Brett Kavanaugh’s legal career had been forged in the fires of the Whitewater probe. He had worked closely with Starr on his staff and authored key chapters of the Starr Report. He referenced that role during his fiery confirmation hearings over allegations he had sexually harassed someone as a teenager. Kavanaugh exclaimed that the lurid stories about his behavior were part of “revenge on behalf of the Clintons.”

Hillary Clinton scoffed at the accusation, saying it “deserves a lot of laughter….I told someone later ‘Boy, I tell you they give us a lot of credit.’”

Knowing the Clintons as well as he did, Ken Starr in his decent and polite way privately agreed with Kavanaugh. In the end, Starr never served on the Supreme Court. But his investigation played a role in fostering the deep, enduring mistrust that kept Hillary Clinton from returning to the White House in 2008 and 2016.