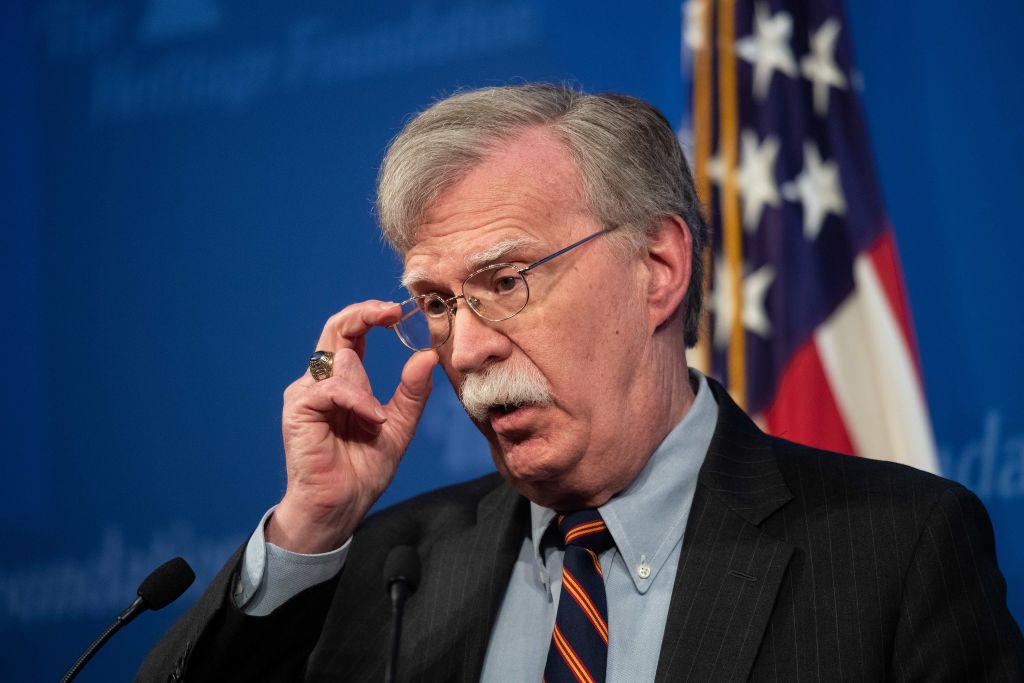

John Bolton has left the White House and those of us who desire some modicum of peace in this world can breathe a sigh of relief. Bolton was appointed to serve as Donald Trump’s third national security adviser barely a year and a half ago, succeeding H.R. McMaster. It was always a strange choice: Trump’s foreign policy is premised largely on hard-nosed (and often hard-of-luck) deal brokering, while Bolton’s preferred method is to bomb other countries. This is the man who has no regrets about the calamitous occupation of Iraq, who wanted to assassinate Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, who seemed to advocate for the use of nuclear weapons against Iran, and who lamented that we didn’t destroy the Syrian regime all the way back in 2003.

Now he’s resigned, presumably so he can spend more time starting wars with his family. Yet that doesn’t mean we’ve seen the end of him. Bolton has served in every Republican administration since Ronald Reagan’s and he may very well fail upwards into the next one too. That could be the case especially if the country is then in a nationalist mood, in the throes of which Bolton always seems to surface. Indeed, Bolton’s most prominent appointments, under Trump and George W. Bush before him, came during deeply nationalist moments in our history.

At first this sounds nonsensical. Trump is a nationalist, certainly. But George W. Bush? Wasn’t he a neoconservative, a globalist, more concerned with exporting liberal values to other countries than tending his own garden? Certainly that was the ideology among some in Bush’s inner clique, who viewed Iraq as the first theater in a charity crusade to democratize the world.

But that wasn’t the way the public understood it, and if it had been, the war might never have happened. To the average mother of three sporting a yellow ‘Support the Troops’ magnet on her car, Iraq was about American security, American vengeance, America exerting its will over another country for America’s own good. It was, in other words, a global project serviced by a nationalist impulse: Francis Fukuyama for the elites, Toby Keith for the people.

It’s into that latter sensibility that Bolton ultimately fits. Terminally wrong though he is, there is something fundamentally American about him, from the tough talk to the cocksure demeanor to the hot-blooded temper to the saloon shoot-out mustache. When Bush recess appointed him to be representative to the UN in 2005, it was comforting in a patriotic sort of way. America could rest easy knowing Bolton would make her presence felt, even if it meant going red in the face and chasing worthless international bureaucrats down a Turtle Bay corridor.

Trump, of course, is pleasing for essentially the same reason, and so it makes sense that the two men found an affinity, at least on stylistic and temperamental levels. There was just one problem: American nationalism had changed since the Bush years. Putting America first no longer meant safeguarding her against the depredations of exotic capitals, not after so many turns on that crank had resulted in so much backfire. What it meant now was shoring her up domestically against the threats of deindustrialization, economic sluggishness, drug proliferation, and chaos at the southern border.

Against the ‘carnage’ in the Rust Belt, the carnage in Baghdad felt remote and abstract, and indeed Trump was elected on a promise to keep America out of such pointless wars. It’s a credit to Bolton’s political maneuvering that he was able to slip in to Trump’s administration despite his views — in part because of his flattery of the president on Fox News and in part because he was a long-time member of the GOP’s monolithically hawkish adviser class. But ultimately Trump’s instincts, if not always his policies, really were antiwar. Bolton’s positions and even his public statements often didn’t sync with the president’s. Ominously Trump didn’t like his mustache.

Bolton had grown obsolete in a country eager to leave behind the international meddling of the aughts and try a little problem solving back home. To be fair to him, Bolton really is something like a nationalist. He was never keen on quixotic neocon dreams of transplanting democracy into Middle Eastern sands, declaring instead that he was ‘pro-American‘ and in favor of ‘protecting the American national interest.’ That’s the language of nationalism, which holds that a country ought to advance its own fortunes rather than acting on airy codes of universal principles. The problem arose with Bolton’s means of advancing that nationalist interest, which always involved, either directly or looming in the background, wars that the public have grown exhausted of.

For that reason, he had to go. But perhaps those of us who are cautiously optimistic about Trump’s foreign policy, who think a small dose of nationalism right now might be healthful, should take a lesson from Bolton. Because like all lunatics, his internal philosophy is very consistent. Nationalism really can mean something far more martial than rebuilding and strengthening Ashtabula and Akron. It isn’t that long a leap from exerting the national will to flexing it across the map.

Matt Purple is the managing editor of The American Conservative.