In the final year of Donald Trump’s presidency, I went to an event at the AFI Silver Theater and Cultural Center in Washington’s Maryland suburbs. The occasion wasn’t a film but an evening with Bob Woodward. He talked about the lessons of Watergate and what it was like to chase down all, or at least most, of the president’s men.

He was, however, pretty coy when it came to talking about the big reveals he would make in an upcoming book about the Trump presidency. “Follow the money,” he winked. He intimated that there would be big revelations about Trump and Russia. What they might be he never said. The reverential crowd of several hundred Washingtonians was ready to burn incense at his feet. But the oracle simply refused to deliver. And when the book came out, it didn’t exactly live up to the hype. Maybe there wasn’t anything he could end up delivering anyway, as the Russia story never really panned out, at least when it came to the idea that Trump was a paid-up Kremlin stooge.

It was vintage Woodward. Fifty years since the break-in that would topple a president, the hero of Watergate has become the stenographer par excellence of various presidential administrations, but doles out information at his choosing.

He forms a stark contrast to his All the President’s Men co-author Carl Bernstein, who has just published the fascinating memoir Chasing History: A Kid in the Newsroom. Bernstein, it can safely be said, is the more imaginative and volatile of the duo. Also the more left-wing. His ideological passions provide an edge to his writing, coupled with the sleuthing abilities he honed as a cub reporter. Put him on CNN and he vents his indignation about conservatives.

Woodward is more cautious. He is the workhorse of the two, pumping out tome after tome about presidential administrations. He has more receipts piled up than the local Safeway. When a cabinet official is wont to deny something, our man pulls out the incriminating document to show that he already has the info. It’s time, in other words, to ’fess up. And they usually do, Democrat or Republican. Even Trump himself blabbed lots of incriminating stuff to Woodward. What it all amounts to, however, is another matter. This totemic Washington figure delivers information, not analysis. It’s good as far as it goes. But more often than not, it doesn’t seem to go very far.

A look at his oeuvre reveals the sources of the problem. One is the sheer fecundity of the man. For the Trump era alone, which spanned four years, Woodward produced no fewer than three books: Fear, Rage and Peril. Each created a brief stir, then was largely forgotten.

Another issue is the reliability of his sources. Take Veil: The Secret Wars of the CIA. It featured a supposed deathbed confession by former CIA head William Casey who, Woodward wrote, acknowledged that he had known all about the dispatch of funds to the Nicaraguan contras from arms sales to Iran. Did it happen? It’s unclear.

But as the New Yorker’s John Cassidy observed, “the real rap on Woodward isn’t that he makes things up. It’s that he takes what powerful people tell him at face value; that his accounts are shaped by who cooperates with him and who doesn’t; and that they lack context, critical awareness, and, ultimately, historic meaning.” Joan Didion declared that “measurable cerebral activity is virtually absent” from his post-Watergate work. But that just isn’t his bag. He presents a cool, Washington establishment perspective masquerading as critical inquiry.

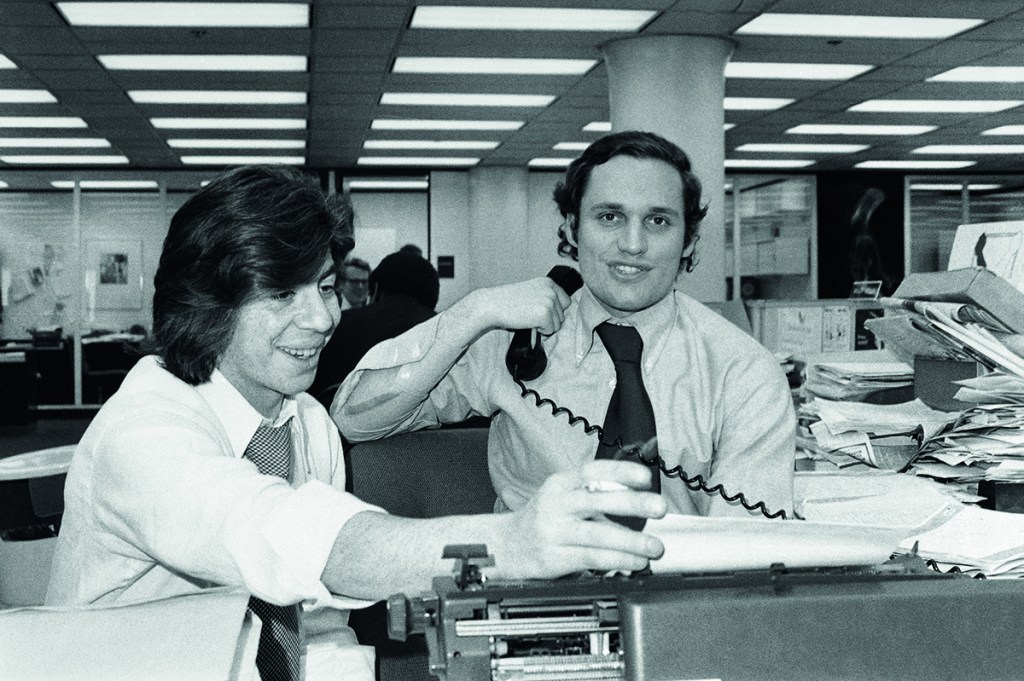

Can something similar be said about Watergate on its fiftieth anniversary? The event is everywhere. The Watergate Hotel, the scene of the crime, has undergone a successful refresh. When you’re put on hold at the hotel, you don’t hear music but excerpts from the Watergate hearings themselves. The Washington Post, where Woodward and Bernstein broke the story, is, among other things, running interviews with such key players from that era as Dwight Chapin. A Starz series has Julia Roberts starring as the combustible Martha Mitchell, wife of attorney general John Mitchell and walk-on part in the scandal.

Even the National Portrait Gallery is getting in on the act with a new show called Watergate: Portraiture and Intrigue. It shows a wide variety of cartoons and photos from the turbulent era itself, including a Richard Avedon portrait from 1976 of Mark Felt, the FBI associate director who was “Deep Throat,” much as Nixon had himself suspected. Felt, like J. Edgar Hoover, was jealous of the prerogatives of the FBI and Nixon’s use of the CIA to help prosecute Watergate helped bring him into bad odor with the powers-that-were at the FBI. This legacy may help to explain Trump’s own innate suspicion of the FBI and James Comey, whom he sacked early in his presidency for refusing to plight his troth.

The exhibit includes an Edward Sorel caricature of Post publisher Katharine Graham observing John Mitchell trapped in a mangle, a reference to Mitchell’s famous declaration that if the Post proceeded to publish unfriendly revelations about Nixon, she would find her tit caught in a wringer. She didn’t. Mitchell, for his part, went to the hoosegow, only to become a subscriber to the Post in his dotage. His life has been chronicled by one of the most assiduous followers of Watergate that I know, James Rosen of Newsmax, in the book Strong Man.

I can’t say that I’m au courant with all the details. All I remember from my childhood was that Nixon was widely seen, at least in my parents’ academic circles, as the personification of everything bad in the world, a rogue who had expanded the war in Vietnam and appeared intent on bringing down American constitutional government with plots involving bombing the Brookings Institution and the like. Today, Brookings stands proudly and Nixon, who engaged in serial rehabilitations of his image during his own lifetime, looks something of a piker next to Trump.

So was the 1970s Sturm und Drang all worth it, from the discovery of the burglars till the day Nixon was evicted, or, if you prefer, hounded, from office? In retrospect it’s hard not to have a queasy feeling. Yes, the system worked. Republicans and Democrats came together, for the most part, to expel Nixon. But Watergate begat more than that.

The desire to become the next Woodward and Bernstein prompted more than a few reporters to become professional scandalmongers. It isn’t right to say that they invented investigative reporting. Their predecessor was in many ways Drew Pearson, the subject of a new biography, The Columnist, by the historian Donald Ritchie. Pearson was a nettlesome presence for Democratic and Republican presidents. A journalistic bloodhound, he had a team of investigators hunting down information about Congress and presidential administrations alike. But he also entered the fray himself, writing speeches for Lyndon B. Johnson.

Watergate ushered in a new era. The press corps now preened itself on its superiority to government officials. This take-no-prisoners style has only ramped up over the decades. Iran-Contra was supposed to take down Ronald Reagan. He would be the new Nixon. Except he wasn’t. The same held for Bill Clinton. First Lady Hillary Clinton had worked on the Watergate hearings herself. Now she was flayed for a White House travel office scandal that was supposed to be of titanic importance. Then came Monica Lewinsky. Clinton’s sexual peccadilloes were elevated into grave matters of state. Republican waxed wroth. The country yawned. Clinton ended up becoming one of the more popular presidents in recent American history. It wasn’t the right that took him down but the #MeToo movement. For the Democratic Party, he is no longer, as the German phrase has it, salonfähig. Instead, he has become a pariah.

You might wonder what Woodward makes of it all. The journalism he helped pioneer has now been adopted by a vengeful right. Had he and Bernstein not helped to bring down Nixon, it might have all turned out quite differently. A Nixon who sailed through his second term would have headed off the rise of the revanchist right. Now, in an instance of what Hegel called the cunning of reason, it is the right, not the left, that is surfing a wave of indignation about the corruption of government institutions and officials.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2022 World edition.