If you followed the nominations of Brett Kavanaugh and Merrick Garland, or the news after Stephen Breyer announced his retirement, you might have concluded that the country has never been more divided on what makes a good Supreme Court justice. Kavanaugh’s hearings were among the most divisive and brutal in history, but he at least had a hearing: Garland’s nomination was dead on arrival in the Senate.

The selection of justices has become a preeminent political issue. Before the 2016 election, Donald Trump released lists of twenty-one potential nominees, almost all Federalist Society choices and rock-ribbed conservative originalists, raising the specter of multiple Hillary Clinton nominees as a critical reason why Republicans, evangelicals, libertarians and others should vote for him: “If you really like Donald Trump, that’s great, but if you don’t you have to vote for m eanyway. You know why? SupremeCourt judges.” During the 2020 campaign, Joe Biden vowed to nominate a black woman to a SCOTUS vacancy; after Breyer’s announcement in late January, Biden reaffirmed his pledge.

Yet the different qualifications touted by presidential candidates smooth out into a set of remarkably similar educational, professional, even geographic backgrounds. Here are two recent nominees. See if you can tell who’s who:

Nominee One grew up in an upper-middle-class family, the child of two lawyers. He attended an exclusive private high school, Columbia University, and Harvard Law, where he graduated cum laude. He won a Marshall Scholarship to Oxford, where he received a PhD in philosophy. He clerked for a distinguished judge on the DC Circuit and then on the Supreme Court, staying in town to work at a top law firm. He served as deputy US attorney general and acting associate AG before being appointed to the federal court of appeals, where he remained for eleven years before being nominated to the Supreme Court.

Nominee Two grew up in an upper-middle-class household in a nice suburb and graduated as valedictorian of a public high school. He graduated summa cum laude from Harvard and went on to graduate Harvard Law magna. He clerked on the Second Circuit before gaining a Supreme Court clerkship. He worked in the Department of Justice for four years, including as deputy associate AG; as associate and partner in a prestigious DC law firm; and as an assistant US attorney. He was then appointed to the DC Circuit and served for nineteen years before his nomination to the Supreme Court.

If you guessed first Gorsuch, then Garland, you are an expert. The differences are so slight, the similarities so striking, that it speaks volumes about the current ideal of a Supreme Court nominee — and just how much that model has changed over the years.

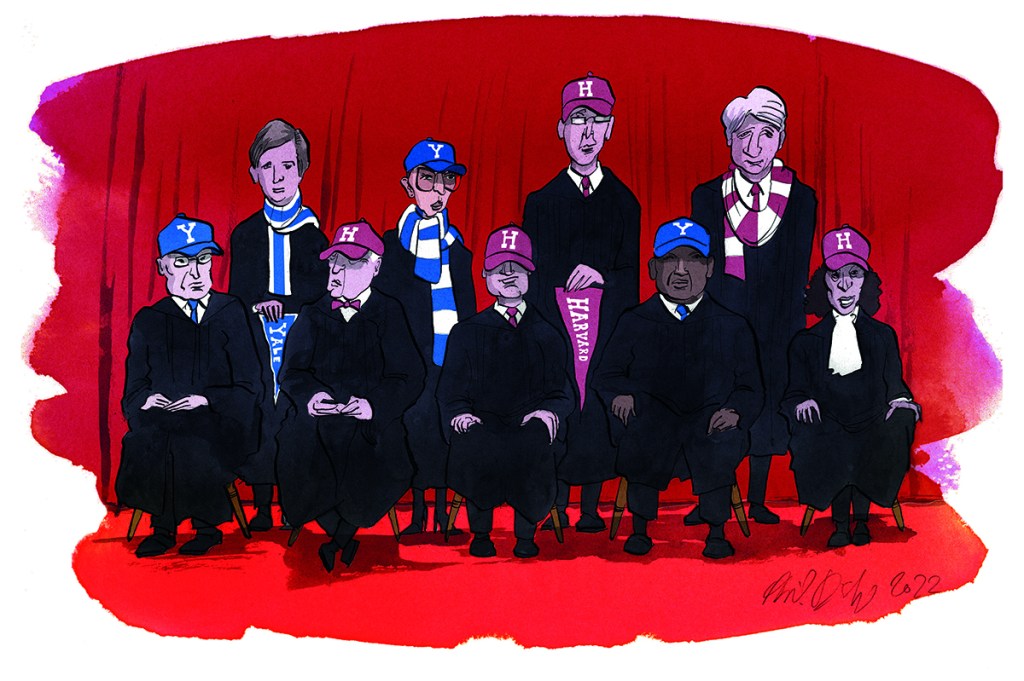

These stories are typical of the entire Court. The last four nominees all grew up in the suburbs of major cities in relatively prosperous, professional homes. Of the other current justices, only John Roberts (Long Beach, Indiana), and Clarence Thomas (Pin Point, Georgia) grew up outside major metropolitan areas. Five had a lawyer parent; five went to high school inside the DC–NYC corridor. Every one except Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett was an undergraduate at an Ivy League institution or Stanford.

Almost every recent justice attended either Harvard or Yale law schools. From the appointment of John Paul Stevens (Northwestern) in 1975 until Barrett in 2020, every justice attended Yale, Harvard or Stanford law schools, then and now among the world’s most selective. Justice Ginsburg’s responsibilities as a young married mother help explain the one pre-Barrett anomaly on the recent Court: Ginsburg attended Harvard Law for two years, but graduated from Columbia after transferring to follow her husband Martin to his job in New York. When Ruth asked Harvard if she could still have a Harvard diploma if she spent her third year at Columbia, they, in their infinite wisdom, declined.

The post-graduation careers of the justices on the Roberts court show where ambitious and academically inclined lawyers with impeccable credentials choose to work. The obvious first step is a Supreme Court clerkship, the most prestigious job a law school graduate can procure. A whopping two-thirds of the current justices were clerks — each of the last four appointed, as well as Merrick Garland. Here again only sexism kept Ginsburg from swelling the ranks. Though she tied for first-in-class at Columbia, Justice Frankfurter declined to hire her: a female clerk was a bridge too far in 1960.

After their clerkships, future justices begin their legal careers among the very best of the best. Historically, this has meant lucrative careers in private practice, often as solo practitioners or in small firms. The current bench, however, reflects a very different kind of work experience. In recent decades, justices have tended to work either as law professors or government or corporate lawyers before eventually serving as federal appellate judges, often on the hyperspecialized DC Circuit.

Justices Scalia, Kennedy, Breyer, Ginsburg, Kagan and Barrett all spent the bulk of their non-judicial careers in even harder-to-get high-level academic jobs: it’s tough to get one of the thirty-six annual SCOTUS clerkships, but top-ten law schools hire only one or two tenure-track professors a year. Still, Kagan, Breyer, Scalia and Ginsburg all reached this academic peak early in their careers. Breyer wrote two enormously influential books; Scalia taught at Chicago, Virginia and Stanford. Ginsburg personally changed the face of constitutional and gender discrimination law. Barrett was the rare Notre Dame Law graduate to be hired to teach there, a remarkable result reflecting her Scalia clerkship. Kagan was dean of Harvard Law; given that there have been 115 justices and only eleven deans of Harvard Law, Kagan’s current job is arguably less rarified than her last one.

Others made no less prestigious ascents. After a stretch as a district attorney and corporate counsel, Clarence Thomas worked for the Missouri senator John C. Danforth and later as head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission under Presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush. Sotomayor spent five years in the Manhattan DA’s office under the legendary Bob Morgenthau. Alito was an assistant US attorney in New Jersey and went on to work in the Solicitor General’s office, which argues and briefs cases before SCOTUS, eventually becoming deputy US attorney general.

Kavanaugh may be the best example of this career path. He jumped from one prestigious and politically helpful job to another before joining the DC Circuit. He assisted Kenneth Starr with the Whitewater investigation for four years; he’s thought to have written much of its final report. Later, he rose to the all-important job of staff secretary in the White House, controlling the flow of paperwork that crosses the Resolute desk.

The top of the American legal profession is a small world, and today’s Court really shows it. The first two Trump appointees, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh, have risen together since high school, even clerking together for Justice Anthony Kennedy in the 1993-94 court term. Both served under George W. Bush, at the Department of Justice and the White House; both were nominated to the court of appeals in 2006. And these are just the obvious overlaps; it’s well-known that they run in the conservative legal circles associated with the Federalist Society.

But elite credentials are not just for Republicans. Remove political leanings from their résumés, and Merrick Garland looks almost identical to Gorsuch and Kavanaugh. Read Alito’s résumé next to Sotomayor’s: they are remarkably similar, from orientation at Princeton to the day each joined the Court.

We live in a time of exceptionally strong partisan divisions, but the divisiveness of American politics in the last decade may mask a bipartisan accord on elite credentials. Donald Trump made the role and nature of American elites perhaps the central electoral issue. Yet when he had the chance to make three Supreme Court nominations, he selected the most elite nominees he could find — apparently he declined to nominate at least one SCOTUS candidate because he lacked Ivy credentials.

The recent justices who most differ from the paradigm have tended to be female or nominees of color: Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett weren’t Ivy undergraduates; neither Sotomayor nor Thomas clerked after graduation. As a graduate of Rhodes in Memphis and then Notre Dame Law, Barrett’s pedigree looks more like that of a justice from a century ago. But with a full ride to Notre Dame and her Scalia clerkship, from law school onward Barrett’s career has converged with the hyper-elite paths of the other law professors on the court.

This elite model has triumphed for three reasons. First, as Supreme Court nominations have become more controversial, the pressure to choose a nominee who can survive both the Senate Judiciary Committee and public opinion has risen. Because the costs of a misstep are so high, presidents are sorely tempted to take credentials off the table altogether, sticking to candidates who’ll receive the American Bar Association’s highest rating, “well-qualified.”

Second, partisans of both parties have become increasingly worried about ideological “drift” on the Court. In recent decades, Republicans have been most concerned, with many on the right arguing that Justices Stevens, Souter, Kennedy, O’Connor, even Chief Justice Roberts, became more liberal during their time on the Court. This has historically been a bipartisan concern, though: liberals expressed concern about conservative drift by Justices Byron White and Felix Frankfurter, among others. Appointing justices from a court of appeals seat theoretically allays this concern, allowing examination of past decisions for evidence of drift or dependability. And law professors generate a lengthy trail of publications that can be mined for signs of ideological coherence. Last, and significantly, the longer the trend continues the more it becomes normative.

Historically, former politicians have been a prime source of Supreme Court justices. But the last one with experience as an elected official was Sandra Day O’Connor, who spent six years as an Arizona state senator, and the last well-known politician appointed was Earl Warren, former California governor and vice-presidential candidate, in 1954. Consider the hullabaloo if a president nominated Elizabeth Warren, Ted Cruz, or Kamala Harris. Americans already object to the “politicization” of the Court, so nominating a partisan politician is a risk few would take. Candidates whose backgrounds are like those of their would-be colleagues seem non-threatening, even comforting.

The similarities may seem benign, but concern over the unvaryingly elite backgrounds of our justices has been rising for some time. Consider Justice Scalia’s dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015):

Judges are selected precisely for their skill as lawyers; whether they reflect the policy views of a particular constituency is not (or should not be) relevant. Not surprisingly then, the Federal Judiciary is hardly a cross-section of America. Take, for example, this Court, which consists of only nine men and women, all of them successful lawyers who studied at Harvard or Yale Law School. Four of the nine are natives of New York City. Eight of them grew up in east- and west-coast States. Only one hails from the vast expanse in-between. Not a single Southwesterner or even, to tell the truth, a genuine Westerner (California does not count). Not a single evangelical Christian (a group that comprises about one quarter of Americans), or even a Protestant of any denomination.

Justice Scalia, alluding to the complicated intersection of the law with the larger culture, does more than just disagree with his colleagues. He challenges the legitimacy of the current Supreme Court altogether. During the summer of 2016, both Justices Kagan and Sotomayor expressed similar concerns, albeit more diplomatically.

Scalia’s Obergefell dissent was published in June 2015; its observations about the Court’s makeup took on particular salience when he died eight months later. President Obama was left with the unenviable task of nominating someone a Republican-controlled Senate might confirm to the Court. As if this weren’t challenge enough, Obama heard echoes of Scalia’s dissent from across the political spectrum: the New York Times’s Adam Liptak and Emily Bazelon both decried the similarity of the justices’ backgrounds. Libertarian USA Today columnist Glenn Reynolds repeatedly criticized their sameness, suggesting electing justices or appointing non-lawyers. Nevertheless, Obama settled on Merrick Garland, as we have seen, a near-facsimile of his prospective colleagues.

The current Supreme Court is packed with Type-A overachievers who have triumphed in a long tournament measuring academic and technical legal excellence. It desperately lacks individuals who reflect other types of “merit.” When you read about the lives of the Marshalls — John and Thurgood — ask if either would be nominated and confirmed today.

It’s clear as well that the overall diversity of life experiences on the Court is likewise falling, even as racial and gender diversity are at an all-time high. Today’s justices have spent more time in elite academic settings or as federal judges than any previous cohort. And it’s hard to imagine jobs that require less contact with the general public: compared to their predecessors, today’s justices have very limited experience as practicing lawyers, and work as White House counsel or in a white-shoe law firm involves little or no contact with “ordinary” Americans.

In the past we used different criteria to select the best candidates to serve as judges; the present meritocratic hurdles ignore, to our cost, what Aristotle called phronesis or “practical wisdom.” (Its less highfalutin cousin is “common sense.”) Aristotle thought that practical wisdom is the foundation for all just decision-making, arguing that it isn’t gained by cloistered study but by living a varied and challenging life. Phronesis is thus eminently practical and to be distinguished from “mere cleverness.”

If the Supreme Court only handled technical legal issues, maybe it would make sense to choose justices solely on their abilities in that area. But the Court has changed. Its most important and visible work is now far more political and policy-based. Is triumphing at every step of elite competition useful if you are to decide whether the Constitution guarantees gay marriage, or whether to overturn Obamacare because of poor legislative drafting?

In his 2019 book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, David Epstein argues that generalists fare much better than specialists when presented with open-ended, real-world problems. Specialists tend to shoehorn problems according to their aptitudes: to a hammer, everything looks like a nail. And to nine specialists in highly technical legal reasoning, every hard question appears well-suited to ninety-page answers with split votes; concurrences in some, but not all, parts; and multiple separate dissents. Read any controversial split decision from the Court in the last decade or so. I guarantee you it will shine as a work of technical excellence. I also guarantee it will be an overlong thicket, in which each justice vies to demonstrate virtuosity and technical skill.

In civil law jurisdictions, the technical legal reading of statutes and broad constitutional policymaking are typically split between different bodies, staffed by different types of judges. In the United States we have chosen to unite these functions in a single court; we should at least consider changing the mix of people who do both jobs at once. Instead, we continue to select justices who are likely to be very good at one job but less successful at the other.

There are other downsides — groupthink, for example. And there is the related difficulty of corralling a group of all-stars, each of whom has been the best of the best his entire career: on the Supreme Court as on the basketball court, there is a danger to gathering too much high-ego talent. The Court has seen this before, notably in the all-star FDR-appointed Courts of the late 1930s and 1940s, loaded with sterling reputations and brilliant minds. Yet dissension and rancor ruled, and the Court splintered over multiple issues.

Similarly, contemporary Courts write longer opinions, and issue more dissents, concurrences and split decisions. In the 2020 case of Ramos v. Louisiana, the Court addressed a relatively obvious and uncontroversial issue: whether non-unanimous jury convictions in criminal trials are constitutional. The justices decided 6-3 on the merit, but with a hideously incoherent and divided series of opinions, mostly because of an ongoing (largely academic) feud about when the Court may properly overrule precedent. Such disproportion reflects various pathologies of the “all-star” mentality, when a mix of different skills might let justices find more room to cooperate, or at least work harder on sublimating their interests to the institution and the people it is supposed to serve.

The time is ripe for a frontal attack on the current prototype. Faith in our elite institutions, the Supreme Court included, is collapsing, with rising disgust on all sides for a rigged system run by and for elites. That was one of Trump’s campaign themes in 2016 and 2020 — and it bears remembering that it was also a central message of Bernie Sanders.

We must convince voters that the Court’s problems run much deeper than an ideological split. Glenn Reynolds’s The Judiciary’s Class War is a good start: he argues that the elite backgrounds of America’s judges influence their decisions, especially at the Supreme Court level, and notes that they’re not left-right issues, but what he calls “front row” and “back row” issues. Commentators on the left agree. Adam Cohen’s Supreme Inequality argues that the justices’ elite background leads naturally to their favoring corporations, and that for a generation SCOTUS has favored business interests and economic inequality, not always along traditional conservative-liberal lines. The Court’s radically fractured opinions in Ramos v. Louisiana raised alarm bells; the New York Times’s Linda Greenhouse called it a sign of a Court in “crisis” and conservative constitutional law professor Josh Blackman stated that parts of the decision left him “flummoxed.”

I’m inclined to offer a piece of advice to future presidents, paraphrasing Trump: What the hell have you got to lose? The focus on elite backgrounds has hardly made the confirmation process smoother. Did Merrick Garland’s A+ term paper smooth his confirmation? Did it hurt Amy Coney Barrett that she was a Rhodes grad? We are now so polarized that going outside the box may make little difference. If Trump had chosen Sen. Mike Lee rather than Kavanaugh, some might have squawked, but would it have been worse than what we got?

We have redefined our idea of greatness, turning away from broad experience and requiring candidates to jump through ever-narrower hoops. Cronyism and nepotism have been powerful for ages: Bushrod Washington became the twelfth justice in 1799 largely because he was George’s favorite nephew. But if an Ivy League BA is a de facto requirement for the Supreme Court, the path for future justices begins to narrow in ninth-grade algebra, which is just too soon.

Justices have lived and practiced all over the country. They’ve fought in wars. They’ve served at the highest levels of the government to some of the lowest, from village postmaster to Postmaster General. They’ve been police court judges and state supreme court justices. They were senators, congressmen, a former president. And a school-board member. Let’s bring back a Court that reflects American greatness in all its bizarre variation: geographic, economic, experiential. Let’s make the Court weird again, with former mayors and Latin professors and ambassadors and journalists and entrepreneurs. If diversity is our strength, let the Supreme Court reflect the richness of true diversity.

Benjamin H. Barton is a professor of law at the University of Tennessee. His books include Fixing Law Schools, Rebooting Justice and Glass Half Full. His new book is The Credentialed Court: Inside the Cloistered, Elite World of the Supreme Court (Encounter, $32). This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2022 World edition.