With infrastructure talks continuing to hit snags, many Democrats don’t believe Republicans are negotiating in good faith. And why should they? During the Obama presidency, when some Republicans initially expressed interest in compromising on major Democratic priorities including health care, climate change and immigration, they would always find some excuse to bail. Why should we expect Republican behavior during the Biden presidency to be any different?

Because today the Republican party has genuine incentive to cooperate.

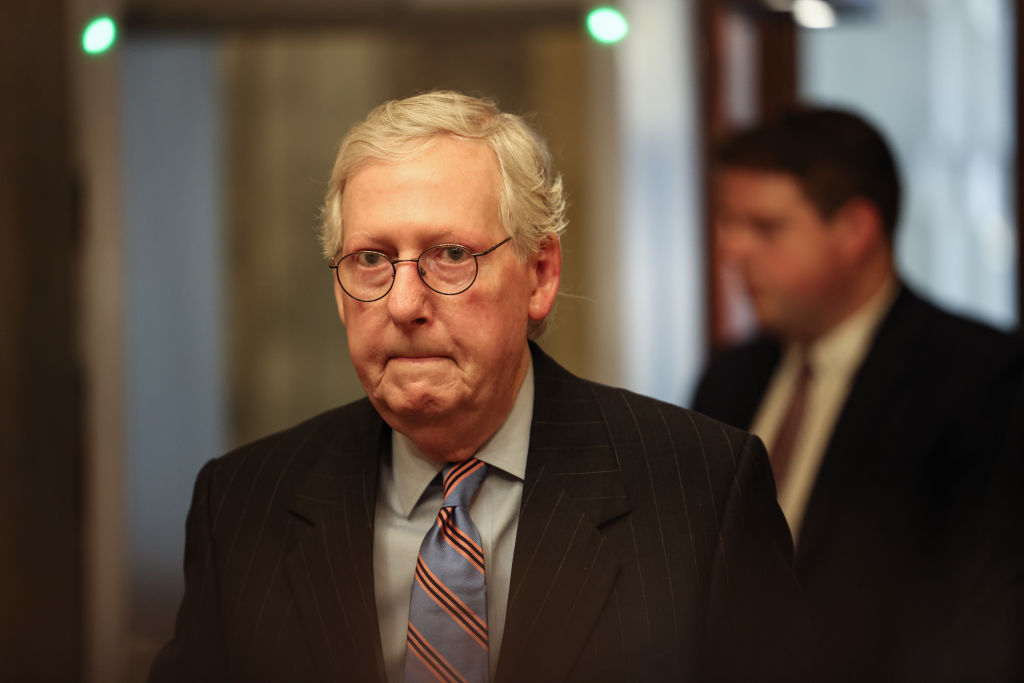

First, Republicans want to shed their obstruction reputation. Many assumed Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell would run the same filibuster-heavy playbook he used against Obama. As described by political scientists Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson last March in the Atlantic, McConnell ‘produced an atmosphere of gridlock and dysfunction for which Democrats [emphasis original] would pay the price’ by filibustering ‘everything that could be filibustered…even routine and trivial matters’.

But this year McConnell has not been generating dysfunction by filibustering routine and trivial matters. So far, Republicans have only filibustered the Democrats’ voting rights bill and their proposal for a bipartisan commission to investigate the January 6 insurrection. Meanwhile, several bipartisan bills have been sent to President Biden’s desk, often with McConnell’s support, including legislation to curtail hate crimes, invest in water infrastructure, prevent Medicare cuts and temporarily extend the COVID-19 small business loan program.

These bills don’t represent the progressive heart of the Democratic agenda. Nevertheless, if McConnell thought maximum dysfunction was in his own party’s interest, he would have filibustered those bills. As he did not, the only conclusion to draw is McConnell does not want his party to be seen as reflexively obstructionist.

Surely McConnell won’t hesitate to filibuster most of the Democratic wish list, as he did with voting rights. But it would help GOP credibility in future obstruction of those wish list items to support a compromise for at least one of them, allowing Republicans to claim they are willing to find common ground and they are only obstructing Democratic overreach.

Second, Republicans don’t want Democrats getting all of the credit. Even if GOP lawmakers wanted to obstruct Democrats on infrastructure, they can’t. Infrastructure is a budgetary matter that qualifies for the Senate’s ‘reconciliation’ procedure, which is immune to filibusters. So Democrats can pass an infrastructure bill with a simple majority on a party-line vote.

That leaves Republicans with two choices: let the other party get all the credit, or get a piece of it for themselves.

There are plenty of Democratic wish list items Republicans would not want the credit for delivering. But traditional, physical infrastructure — such as roads, bridges, water and broadband — has a long history of attracting bipartisan support. According to Politico, McConnell’s advisers ‘say he understands the bipartisan appeal of infrastructure and views it as less ideological than other Democratic priorities’, which helps explain why Kentucky’s senior senator has been ‘privately telling his members to separate [the bipartisan infrastructure] effort from Democrats’ party-line $3.5 trillion spending plan’.

Third, if they can’t easily obstruct, Republicans can at least restrain how much Democrats accomplish. To the extent Democrats can keep their caucus unified, they can deliver all the bacon they want. Moderates like Sen. Joe Manchin will have some sort of mitigating effect, but any effort to woo 10 Senate Republicans will require more substantial narrowing.

Moreover, the White House has indicated Democrats won’t use reconciliation to spend more on the physical infrastructure items covered in the bipartisan bill. Therefore, in a bipartisan agreement, the Republicans can wield enough power to contain how much is spent on traditional infrastructure, even if they can’t on other areas where Republican opposition compels Democrats to use reconciliation, such as nontraditional infrastructure.

Of course, this analysis does not automatically mean Republicans will cough up enough votes on infrastructure to overcome any attempted filibuster. Perhaps they will get spooked by intensifying grassroots conservative opposition. Perhaps Democrats will make one demand too many.

But we should recognize that a Lucy-and-the-football explanation for Republican cooperation to date is not the only explanation. The political reality is that shaping America’s infrastructure strategy helps Republicans more than ceding America’s infrastructure strategy to Democrats.

Bill Scher is a contributing editor to Politico magazine, co-host of the Bloggingheads.tv show The DMZ and host of the podcast New Books in Politics. This article was originally published on RealClearPolitics.