Death panels are real. They are a potentially unavoidable part of a health catastrophe like coronavirus. We won’t call them death panels, of course; that would be unnecessarily inflammatory. But in the event that hospitals have more patients requiring life-saving treatments than are available, someone will have to decide who goes without.

Dr Matt Wynia is the director of Center for Bioethics and Humanities at the University of Colorado. He explains, ‘You do not want the bedside team being forced to shoulder the burden of making treatment decisions about their own patients.’ His foremost concern is that bedside doctors cannot be expected to maintain situational awareness of what resources are available in their hospital, city, or state. It would be quite unacceptable if someone were to die because they were denied a treatment, on the basis of rationing, that actually was available down the street.

Federal agencies, as well as state health departments and individual hospitals have drawn up documents outlining the creation of ‘triage panels’ to make these decisions instead.

Justification for the creation of these panels are given in some of the documents. A CDC document on ‘Ethical Considerations Regarding Ventilator Allocation’ presumes that treating physicians will always ‘attempt to interpret priority rules in a way that favors the access of their own patients to scarce life-saving therapies’. Surely an arms-length organization will make better decisions, unencumbered by personal connection?

A ‘Crisis Standards of Care Planning Guidance for COVID-19’ document published by the Massachusetts Office of Health and Human Services on April 7 urges every acute care hospital in the state to create a ‘Triage Team’. The Triage Officers on these teams are expected to make decisions ‘designed to benefit the greatest number of patients, even though these decisions may not be best for some individual patients’. Patients will be scored on a two-step, eight-point scale.

The first step awards one to four points based on how ill the patient is. One point if they are mildly ill, four points if they are almost certain to die no matter what is done. The second step awards points for how bad their baseline health was prior to COVID two points for significant health conditions, four points for severe. In the event of a shortage of lifesaving treatments, patients with the highest scores will go without.

Pregnancy is not considered in this scoring system, unless the fetus is thought to be ‘viable’. If so, two points are subtracted from the mother’s score.

Such decisions are likely to be contentious. Presumably, this is why the Massachusetts document demands that Triage Officers have ‘effective communication and conflict resolution skills’.

Dr Wynia believes that ‘triage teams should not have access to information about the race of the patient, or their socioeconomic status. We know that if you walk into a room and see someone those things influence your decision, even if you don’t want them to.’ He views the ability to blind triage teams to these factors a significant advantage over having bedside doctors make these decisions.

It should be noted that most of these documents describe not only how to ration who gets a ventilator in the first place, but also gives triage committees the ability to unilaterally remove ventilators from patients if circumstances change. Outside of a pandemic, such a maneuver is generally prohibited by law.

The state documents have more in common than not, but their differences are interesting. A 2015 New York State planning document specifically prohibits use of ‘advanced age’ in triage committee decisions. Children will be given priority but a 27-year-old and an 87-year-old would receive equal priority. Massachusetts and Maryland would use age but only as a tie-breaker.

***

Get three months’ free access to The Spectator USA website —

then just $3.99/month. Subscribe here

***

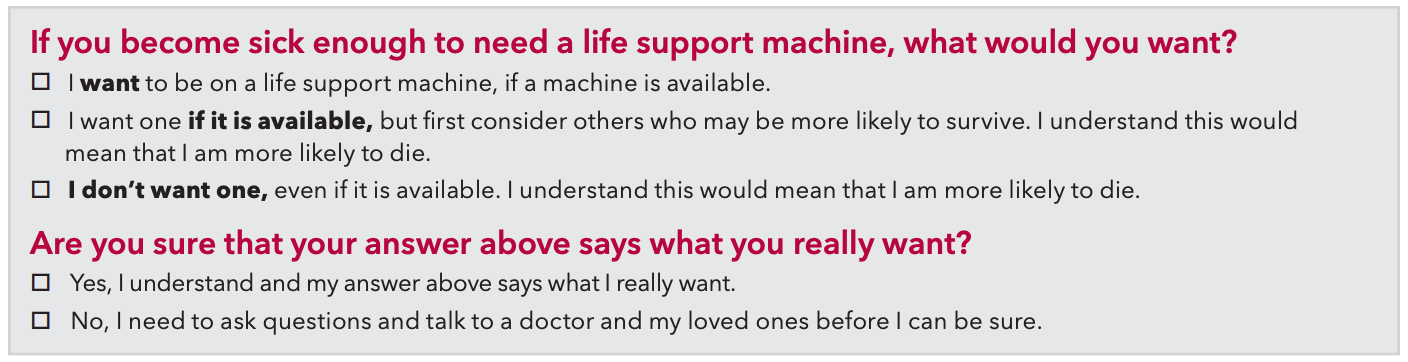

Dr Wynia notes that failing to consider age might go against our common sense: ‘When you talk to both ethicists and just people in general, most people take it as intuitively obvious that if you had two people sick at the same time, one is 35 and the other is 75, and they have an equal chance of surviving that you might give preference to the younger person.’ However, his interest seems to be in asking folks to make these considerations themselves rather than urging triage committees to do it. His group at the University of Colorado have prepared a decision support tool that specifically asks patients whether they would be willing to forego use of life support in order to give someone else a chance of survival:

It remains to be seen what proportion of elderly patients might choose to take themselves out of the line. Most young people can’t imagine checking the second box. However, as a critical care doctor myself, who has had so many conversations around these issues outside of a pandemic, I would not be surprised to see many people of advanced age make that selection. Just yesterday, a cheerful 84-year-old woman told me she was choosing to pass on life-saving surgery because ‘I’ve already lived my life!’

It would be rather ironic if all of the pre-planning around crisis standards of care and triage panels was largely obviated by simply asking people if they’d be willing to bow out.

Matt Strauss is the former medical director of the critical care unit at Guelph General Hospital, Canada. He is now an assistant professor of medicine at Queen’s University.