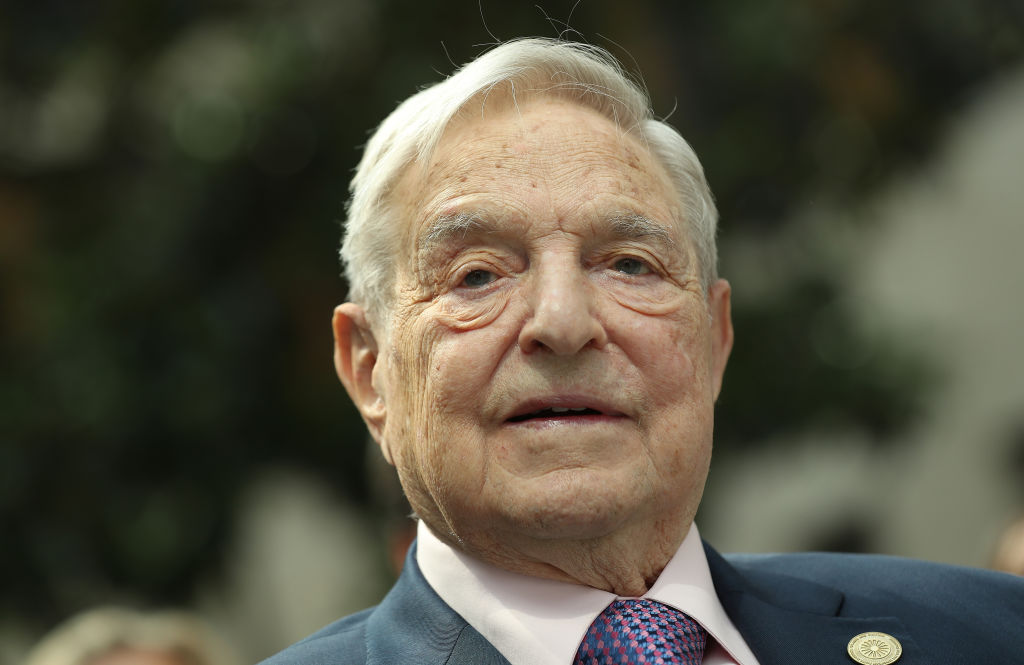

The Financial Times has picked George Soros as its Person of the Year for 2018. Soros is my person of the year too, but the year is 1996. He represents a style of economics and politics that looked set to conquer the world in the Nineties, but which is now repudiated whenever people get the chance to vote, and wherever people don’t get the chance to vote at all.

‘The Financial Times’s choice of Person of the Year is usually a reflection of their achievements,’ the FT explained. ‘In the case of Mr Soros this year, his selection is also about the values he represents.’

Soros’s values are not all bad, but their repudiation at the ballot box is not all good. He has made millions in the markets, which makes him odious to most people, but he has given generously; an estimated $11 billion between 1979 and 2011. He has been especially generous in building the institutions of civil society in the ex-Soviet states of central and eastern Europe, notably through funding the Central European University in his native Hungary, which the oafish Viktor Orbán has pushed into exile in Vienna. Yet Soros’s politically biased funding of NGOs amounts to an intrusion into the affairs of other nations.

Soros is a prime example of the potential and contradictions of classical liberalism. He is, after all, the man who used Karl Popper’s General Theory of Reflexivity to identify value discrepancy in the British pound, then shorted it on Black Wednesday 1992, making about £1 billion in a day. Soros has also named his philanthropic institute the Open Society Foundation, after Popper’s division of societies into ‘open’ and closed’ in The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945).

Like Edmund Burke with the French Revolution, Popper was describing Europe’s recent past and guessing its future. Like Burke, Popper guessed right. In the Cold War, Europe was sharply divided between open and closed societies, and so was much of the rest of the world. As Animal Farm, another backward-looking prophecy from 1945, has it: ‘Four legs good, two legs bad.’

Popper chose freedom over tyranny, and law and the market over the secret police and Stalinism. The academic left in western Europe and the United States have never forgiven him for being right. But Popper was a philosopher, which is to say, a theoretician. In abstract terms, societies might head towards the antipodes of ‘open’ and ‘closed’, but the people who make up societies tend to mill about on the darkling plain between these extremes. Since 1945, most people in Western democracies have broadly agreed with ‘Four legs good, two legs bad.’ But the aggregate of their votes shows that they want the state to be a three-legged animal.

The people want free markets and healthcare. The people want to make money from exports, but they don’t want to import cheap labor or angry foreigners. These are the simple facts of liberal democracy as it now is. They are not blips, but reflections of a slow-simmering trend that rose through the fat years of the Nineties and Oughts, which has repeatedly risen to boiling point since 2008. Given the rise of Chinese influence and the decay of American institutions, this trend is only going to become more severe as the lean years become the new normal.

If we are to preserve liberal democracy and free markets, then we must accommodate liberal democracy in order to keep markets as free as possible. The FT and Soros would say that the ‘populist’ Western publics have got it wrong, because prosperity is up and unemployment is down. Isn’t that precisely the three-legged animal that the voters have wanted since 1945?

Yes and no. The current model has one foot in the domestic market economy and the other in the domestic welfare state, as it always has. But its third foot is in the wrong place because the ground has shifted.

Many voters no longer want that third foot to be in a globalized, borderless economy. That is because they, unlike George Soros, the editors of the Financial Times, and gadfly cosmopolitans like me, live with the social consequences and societal incoherence that are globalization’s side effects. Hence the potential and contradictions of classical liberalism: enormous potential to generate wealth and create a decent nation state, but a contradictory potential to globalize the very forces which will undo the compacts of nation and state.

Thirty years, fostering liberal democracy meant encouraging open borders and expanding the European Union. Huge gains were made, and mostly to the good. But the world has changed. Today, preserving the gains of liberal democracy means that the state must respect its compact with its citizens, and the founding values of culture, kinship, and a social safety net. Today, foreign influence in domestic politics means Russian trolls as well as Soros’s neoliberal subsidies. Today, the European Union is the antagonist of liberal democracy and the nation state. And the more the political generation of the Nineties patronize the voters by denouncing ‘populism’, and promote ‘values’ that create financial value while eroding social capital, the more they pour ‘globalist’ fuel on the fire.

The FT is rewarding Soros less for his achievements than for his values. The tragedy of Soros, and the reason that he is yesteryear’s man, is that his values are now undermining his achievements.

Dominic Green is Life & Arts Editor of Spectator USA.