Libertarians and conservatives “share a detestation of collectivism,” wrote Russell Kirk in 1981. “They set their faces against the totalist state and the heavy hand of bureaucracy. That much is obvious enough.” But he asked “what else… conservatives and libertarians profess in common.” “The answer to that question is simple: nothing. Nor will they ever have. To talk of forming a league or coalition between these two is like advocating a union of ice and fire.”

On a practical level, Kirk may have been overstating his case. At the time that he was writing, a strategic alliance between libertarians and conservatives made a good deal of sense. Communism abroad and progressive collectivism at home were the great challenges of the day. But this was — or at least, it should have been — a marriage of convenience. The “fusionist” idea, which holds that conservatives and libertarians could be compatible on an ideological level, was always a step and a half too far.

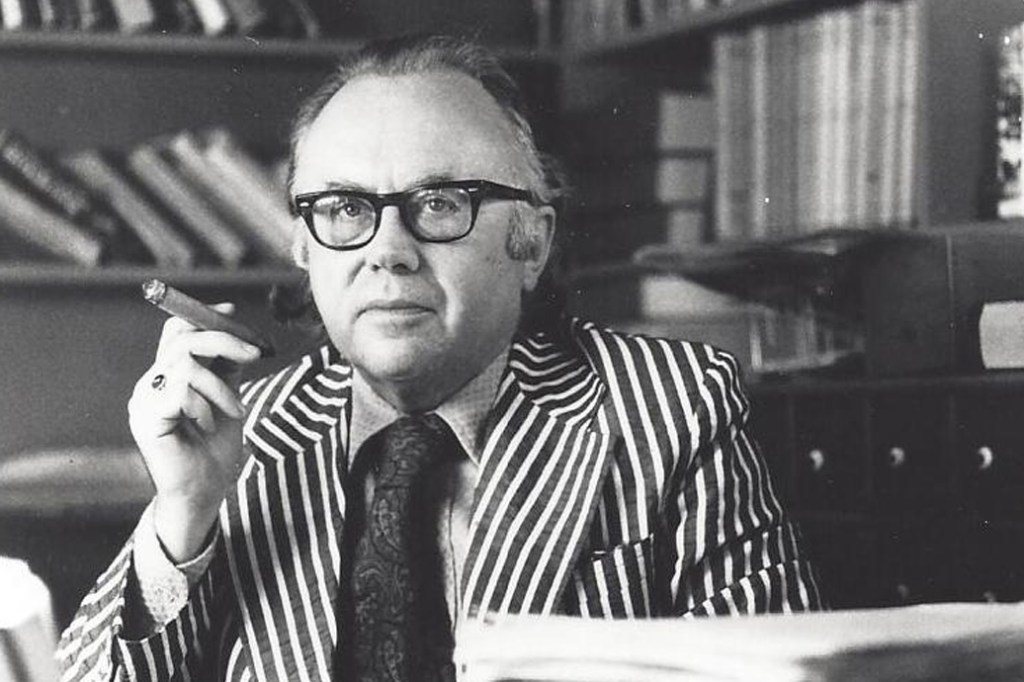

Fusionism’s philosophical progenitor, Frank Meyer, presented conservatives with an admittedly attractive proposition: Libertarian means (individual freedom) are essential for conservative or traditionalist ends (virtue). The essence of this ideological compact — indeed, the organizing principle of fusionism itself — is that virtue must be freely chosen. Man “must be free to choose his worst as well as his best end,” Meyer wrote in In Defense of Freedom. “Unless he can choose his worst, he cannot choose his best.” In practice, as he explained in a 1962 column for National Review, “the simulacrum of virtuous acts brought about by the coercion of superior power, is not virtue, the meaning of which resides in the free choice of good over evil.”

Can virtue exist in the absence of free choice? From the conservative perspective, the answer is: it’s complicated. Liberty and virtue are inextricably intertwined. Free will is written into the Judeo-Christian anthropology, beginning with Adam and Eve’s rendezvous with the tree of knowledge. But as Kirk wrote, “the ruinous failing” of libertarians “is their fanatic attachment to a simple solitary principle — that is, to the notion of personal freedom as the whole end of the civil social order, and indeed of human existence.” In practice, fusionism is no different. Whatever name it goes by, a politics that takes the autonomy of the choosing individual as its first principle inevitably degrades the natural limits and constraints on human action that conservatives rightly see as necessary for freedom to prosper. In this sense, fusionism inevitably reverts to libertarian ends as well as means. For conservatives, this is not a brokered agreement but terms of surrender.

Freedom matters. We should resist the effort, now popular in some corners of the right, to remake American conservatism in its European counterpart’s image. But an authentically American conservatism is rooted in the traditions, customs and ways of life that are unique to this shared home of ours. We are not an “idea,” nor an abstract compact of individual rights-bearers, but a living, breathing political community. And communities require stewardship.

Virtue is not arrived at through mere individual contemplation and choice; it is formed. And it is formed by civic institutions that take a proactive interest in the character of the people. In the traditional understanding of self-government, society had “an obligation to educate [citizens] into what used to be called ‘republican virtue,’” Irving Kristol wrote in his essential “Pornography, Obscenity and the Case for Censorship.” This requires caring “not merely about the machinery of democracy but about the quality of life that this machinery might generate.”

Particularly in our contemporary civic deterioration, self-government also requires a politics that takes limits at least as seriously as liberties. Fusionism has it backwards. Virtue and order are crucial prerequisites to freedom — not the other way around.

Nate Hochman is an ISI Fellow at National Review and a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow for 2021-22. This article is one excerpt from “Fight for the right,” a symposium on the future of American conservatism. Read the full series here.