In nearly every state, the legislature is nervous about the public universities it finances. And fair enough. Apart from sports, the state colleges in America tend to make the national news only when protests break out, and protests tend to be driven by a radicalism that reveals the school protesters are far to the left of the legislatures of even the more liberal states.

Such national news embarrasses the legislators, who send querulous letters to the school officials, with distant threats of cutting state funding. Which tempts those officials to surrender preemptively to activists, in the hope of avoiding protests. Conservatives in America typically blame the radicalism of college administrators for, say, the academic banning of conservative speakers on campus. And that may well play a part. But it is a fundamental bureaucratic rule that one should hesitate to assign to ideology what can be explained by spinelessness. Like children with Battered Child Syndrome, the higher reaches of American college administration tend to imagine that a good day is a day in which no one notices them — a day in which the school doesn’t make the news.

There’s another element at play, however. Another chassé in the stylised waltz of American educational politics. National reporting about college unrest makes state politicians wonder what is happening at their local universities. Even Washington’s liberal state legislature was disturbed by news about protests at Evergreen State College in 2017 (which led to a 10 per cent budget cut at the school), while the Republican-dominated legislature in Missouri was outraged by the radical protests at the University of Missouri in 2015 (which left enrollment still down more than 25 per cent). And the generally populist state legislatures in the American West and Midwest have begun to eye their state-financed colleges, despite the absence of major incidents.

You can see the dance proceeding, for example, even in the relative quiet South Dakota. Leaked documents, sent to me last week, suggest that the legislature is set for a clash with the state universities and the Board of Regents that oversees them. Last academic year — after the University of South Dakota received a negative rating from the free-speech organisation FIRE — the legislature introduced legislation that would have limited the schools’ ability to ban campus speakers for ideological reasons. The bill was set aside after considerable opposition from the Board of Regents, unhappy with legislative attempts to meddle.

A few months later, in the spring, the Board of Regents lost both its executive director, Michael Rush, and its president, Bob Sutton. This may not have been directly caused by the political battle, but it does at least suggest that it’s not the best idea for state bureaucrats to pose themselves against the state legislature. And over the summer, House majority leader Lee Qualm sent a five-page letter to the Board of Regents demanding answers to 19 questions about what the legislature believes are leftist policies at the state colleges, especially regarding free speech.

Thus, for example, Qualm asks whether the Regents ‘view the absence of intellectual or viewpoint or political diversity among professors on South Dakota campuses as a problem’. And, given that administrators at South Dakota State University have the power to remove posters they deem ‘non-inclusive’, what is the school’s official definition of ‘inclusive’? For that matter, testimony during the last legislative battle indicated that ‘one of the sources of pressure leading to restrictions on campus free speech comes from the offices of diversity/inclusion/equity on each campus’. So the majority leader demanded that the Regents ‘describe in detail the nature of these offices, their size, their budgets, their duties, and who is employed by them’.

On September 14, in reply to the July queries, the new Board of Regents president Kevin Schieffer sent a three-page letter. It was, in truth, as friendly and ameliorative as it could be, given that it was accompanied by 36 pages (plus 387 pages of attachments) that were cold and unyielding as the Board of Regents staff could get away with. Thus, for example, Schieffer writes about the need for ‘South Dakota common sense’ to balance ‘the Board’s desire for and support of aggressive free speech policies’ with ‘Title IX mandates, financial limitations, and sound educational objectives’. Meanwhile, the staff report denied reports of an incident involving a film at the University of South Dakota, insisted that existing policies are already generally good, and noted that those policies were being potentially revised anyway at the Board of Regents meetings this October and January.

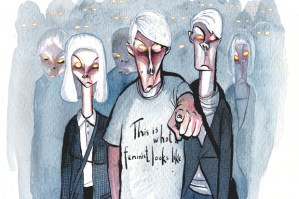

The old liberal demand for free speech (enshrined in adulatory accounts of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement of 1964) is being battered these days by a newer liberal demand for protection from offense. Given the general leftward drift of American colleges over the past 40 years, the transition may indicate nothing more than the fact that everybody praises dissent until they win, becoming the ones dissented against. But one way or another, ‘free speech’ has now become a rallying cry for those perceived as academic conservatives — with ‘free speech equals hate speech’ the counter-chant from academic radicals.

In South Dakota, the state legislature wants the state universities to join the 46 other colleges around the nation that have adopted the full-throated defense of free speech in the University of Chicago’s 2015 statement of principles. South Dakota’s universities want…well, it’s not clear what exactly they want. Mostly to be left alone, it seems. In some part that may be because, like fearful children, they want not to be noticed, never surfacing in the national news or rising to the notice of the legislature. In larger part, though, it stems from a wish that they could walk a middle path: affirming free speech to appease one side while banning what is seen as hate speech to appease the other side.

There’s something a little sad, a little plaintive, in Kevin Schieffer’s suggestion that ‘South Dakota common sense’ can balance ‘aggressive free speech policies’ with ‘sound educational objectives’. In another time, a specifically Midwestern solution might have been available. But the argument today isn’t really arising from local schools. Instead, it’s one of the interesting cases of a national issue casting its big shadow down on the small places of a Midwestern state. And once the question is free speech, an old liberal idea with a new populist edge, the battle of South Dakota’s legislature against South Dakota’s colleges seems inescapable.

And given the fact of the battle, the colleges are wrong. They’re wrong politically, since the legislature really does rule them — and politicians in a reelection fight would welcome the publicity of fighting for free speech. And even more, they’re wrong intellectually. If a fight over free speech and academic freedom there has to be, the only moral choice is to affirm them. Bad stuff may come — but worse always comes from censorship.

Joseph Bottum is director of the Classics Institute at Dakota State University.