I flew from Seattle down to Las Vegas the other day to watch the Rolling Stones in action. Great show, Kafkaesque journey. There are times in life when the miseries of the world threaten to engulf us, when the precariousness of the human condition, far from appearing a worthwhile and even noble struggle, seems an infinite rebuke. That’s the way I feel when I pass through a modern-day American airport.

Many Spectator readers will be familiar with the ordeal. It was shortly after 6 a.m. when I boarded my outward flight, and my reporting skills perhaps weren’t at their best. Nonetheless, I made a note of some of the many exhortations, appearing in either written or spoken form, that enlivened the morning. Stand here. Look at the camera. Give us your laptop, phone, and water. Take off your shoes. No jokes. Don’t disrespect the staff. Be courteous. Wear your mask at all times. No outside food or beverages. Your patience is appreciated. Have a nice flight. And so on. This is how we travel from city to city nowadays in the free world.

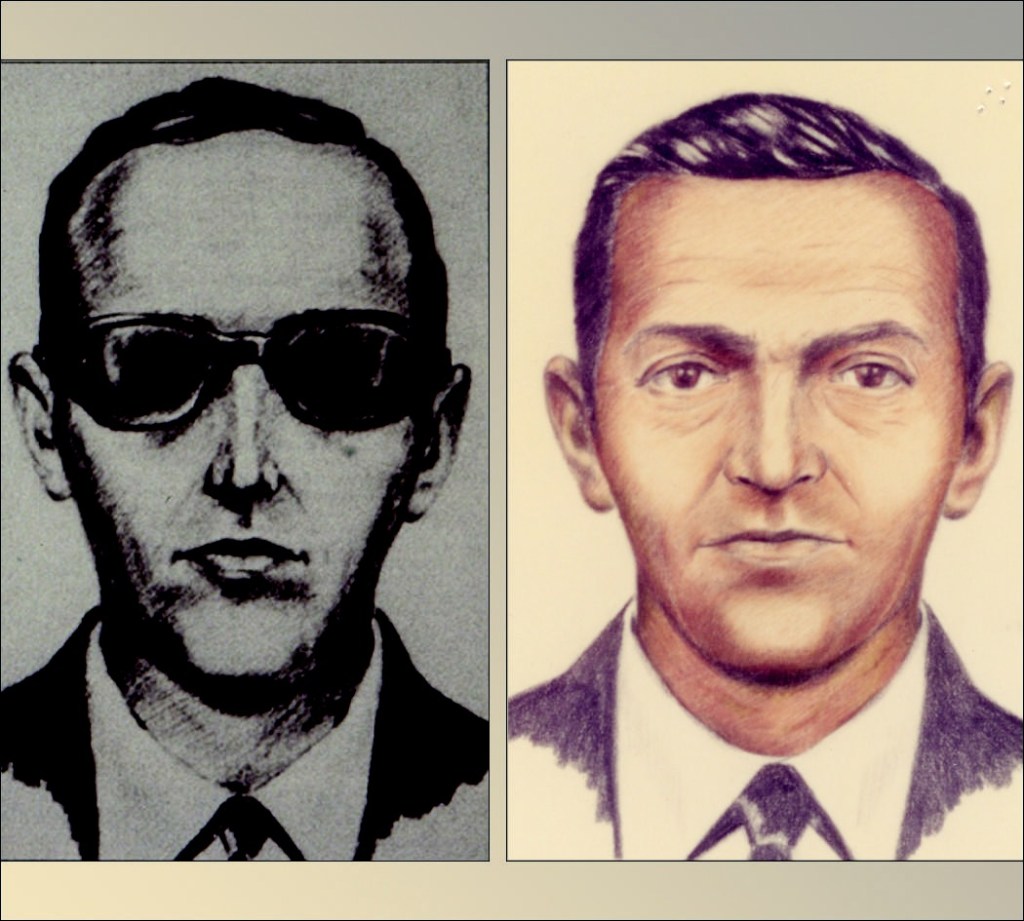

Compare this to fifty years ago, on the dark Northwest afternoon of November 24, 1971. It was Thanksgiving eve, and shortly after lunchtime a middle-aged man wearing a black suit and carrying a briefcase approached a ticket desk at Portland airport. He identified himself as “Dan Cooper” and used cash to purchase a seat on the next forty-minute flight north to Seattle. There were no metal detectors or X-ray machines for him to pass through, and had Cooper so wished he could have simply strolled onto the plane and paid the stewardess for his ticket once in the air.

This was how ordinary Americans then moved around the country. Most domestic flights were as informal as catching a bus. Airlines didn’t limit the number of carry-ons, and you could take pretty much whatever you wanted on the plane. A rehoboam of 200-proof vodka? Absolutely. The samurai sword your dad had brought back with him from wartime Tokyo? No problem. The only note of unpleasantness came with the regular hijacking of planes operating in the southeast with the demand that they be flown to Cuba. To make the detour more streamlined, cockpits were routinely equipped with charts of the Caribbean. Flight crews were told to comply with all hijacker demands. The idea was to make the whole process as quick and painless as possible for the other fee-paying passengers.

Once on his flight to Seattle that November afternoon, Cooper enjoyed a drink and a cigarette (those were the days), and then summoned a stewardess. He told her that he had a bomb in his briefcase. He wanted $200,000 in “negotiable American currency,” four parachutes and a fuel truck standing by to meet the plane on arrival. The stewardess later described him as neat, courteous and soft-spoken. After enjoying a second bourbon, Cooper paid his drink tab, and calmly remarked, “I don’t have a grudge against your airline, Miss. I just have a grudge.”

The plane then landed in the rain at Seattle, where it spent two hours parked at a distant gate. The authorities complied with Cooper’s demands, bringing him the cash and parachutes he requested in return for him releasing the other passengers. After that, he politely asked the pilot to set a course for Mexico City, inviting him to make another refueling stop along the way. Gathered in the cockpit after taking off again, the crew felt a bump while flying somewhere over Vancouver on the Washington-Oregon border. They found no trace of Cooper or the cash when they landed in Reno two hours later.

And that was it.

Did Cooper successfully bail out with the ransom money, and make his way to safety through the wooded terrain of southern Washington, which was then dark and enveloped in freezing rain? Or did he fail to survive the jump, dressed as he was in unsuitable clothing and footwear? No one knows for sure, although in 1980 a young boy found a rotting package of $20 bills totaling $5,800 half-buried in a riverbank about ten miles from Vancouver. The serial numbers matched the Cooper loot. Nobody has ever satisfactorily explained how it got there, nor what happened to the remaining $194,200, which was pretty good money at a time when a gallon of gas cost 35 cents.

The authorities may not have brought Cooper to book, but needless to say they wasted little time in punishing the rest of us. Thanksgiving 1971 marks the beginning of the end for unfettered commercial air travel. Within a year, the FAA had instituted universal physical screening of passengers, and — at least in theory — started inspecting all carry-on bags. The 1974 Air Transportation Security Act added another layer of rules and regulations, although it took the horrors of 9/11 to finally bring about the flying conditions we enjoy today, with their mystifying rules about which size of toothpaste is acceptable and which, conversely, could possibly be used to concoct a bomb. Cooper also had a lasting impact on aircraft design. Starting in 1972, all larger commercial jets were fitted with a paddle-shaped external latch to prevent anyone opening the rear door of a plane while in flight. Officially described as a “Ventral and tail-cone exit inhibition device,” the gizmo goes by the more popular name of a Cooper Vane.

In July 2016, the FBI announced that after forty-five years it had decided to “redirect resources allocated to the Cooper matter to focus on other investigative priorities.” Our boys in black didn’t say what those priorities might be, and no doubt there are some worthy cases among them. By a coincidence, that happens to have been the same month in which “Australian officials” told “American officials” that Donald Trump’s presidential campaign advisor George Papadopoulos had told the Australian High Commissioner in London — still clear? — that “Russian officials” were in possession of “potentially damaging information” on Trump’s challenger Hillary Clinton, and invited the feds to jump to it and investigate tout de suite. You know the rest.