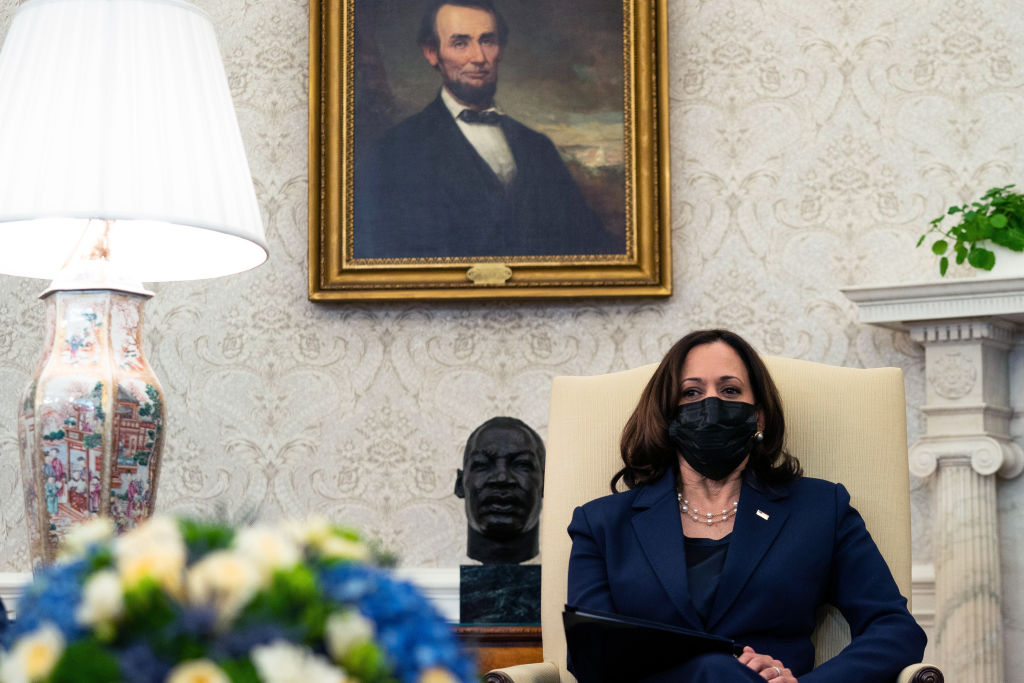

President Biden has stirred some controversy in recent days by his apparent preference for the word ‘equity’ over the word ‘equality’ in dealing with social issues. Most notably he issued an executive order on housing on January 26, framed as a step toward realizing his ‘agenda for advancing racial equity’. The White House ‘Fact Sheet’ mentions ‘equity’ 11 times, and ‘equality’ not at all. In his ‘Remarks by President Biden at Signing of an Executive Order on Racial Equity,’ the President employed ‘equity’ 10 times, stumbling once where he began to say ‘equal…’ Elsewhere, Vice President Harris has helpfully explained, ‘There’s a big difference between equality and equity. Equality suggests, “Oh, everyone should get the same amount.” The problem with that, not everybody’s starting out from the same place.’

Biden and Harris are using the word ‘equity’ in a relatively new sense. The idea of ‘equity’ originated in the English Middle Ages as a useful way to distinguish the things that a person can own outright, such as a house or a pig, and the things in which a person might have a partial financial interest, such as a share in a business. A body of law evolved, centered on contracts, to ensure that such shared financial interests were protected fairly. Today, when we speak of something like a mortgage on a house, the portion of the value of the property in excess to what is owed the lender is the ‘owner’s equity’. Equity can get a lot more complicated than that but if you stick to the idea that equity means something like your fair share, you won’t go far wrong.

Or maybe you will if you enter the funhouse of progressive ideas of ‘fairness.’ Let’s imagine society is a bottle and wealth is the wine within it. What if fairness doesn’t mean your share of the wine by prior agreement, but your sense that society owes you more than that? What if the grapes were grown on land once tilled by your grandfather? What if the wine casks were assembled by your relatives? What if your brother designed the label on the bottle? What if the compensation your ancestors received was less than you think would have been appropriate? In the name of equity, shouldn’t you get a double pour?

The popular term for this redistributionist concept is ‘racial equity.’ A US Civil Rights Commission report mentioned the phrase in 1959. Going by Google’s n-gram generator, the concept had a small boom in the 1960s, another peak around 1980, but has zoomed in popularity in the last decade. The concept advanced through the efforts of two types of sponsors, think tanks and philanthropic foundations, sometimes working together.

In 2005, for example, the Aspen Institute and Annie E. Casey Foundation held a roundtable, ‘Understanding Structural Racism and Promoting Racial Equity.’ The terms were sufficiently novel at that point that the roundtable explained ‘We first must believe that racial equity is all our business,’ and then explained, ‘racial equity refers to the distribution of society’s benefits and burdens in ways that are NOT skewed by race. We believe Racial Equity is an appropriate yardstick for determining what is right or “fair” with respect to social outcomes.’

These claims were part of a PowerPoint presentation that went on to describe the many ways the participants in the roundtable could advance the racial equity agenda. I don’t know that this particular conference was a benchmark in the history of the ‘racial equity’ concept. I suspect otherwise. As I search through old postings, this conference was one of many. Perhaps a stronger claimant was the creation in 2003 of the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity which published practical advice such as Grant Making with a Racial Equity Lens. It was a progenitor of hundreds of similar how-to initiatives, including the 2015 Government Alliance on Race and Equity’s Racial Equity Toolkit: An Opportunity to Operational Equity, and the 2017 consulting firm FSG’s The Competitive Advantage of Racial Equity.

By 2015, it would have been hard to find any major foundation in the United States that wasn’t explicitly devoted to ‘racial equity’. Ford, Rockefeller, Lumina, Kellogg, etc. A key player is the Bridgespan Group that is wholly about ‘Racial Equity in Philanthropy’. Bridgespan explains itself as ‘committed to racial equity and racial justice. We stand in solidarity with those standing up for Black lives and against police brutality,’ and it offers its help to others — NGOs, philanthropists and investors — seeking to walk the same enlightened path.

Assistance for would-be activists is everywhere. If you are ready to plunge into equity activism but haven’t quite mastered the lingo, you might turn to the Racial Equity Tools Glossary. Mostly it covers familiar terms with up-to-date new meanings — such as collusion, colonization, and inclusion — but it also offers authoritative definitions of terms such as ‘racial equity’, to wit:

‘Racial equity is the condition that would be achieved if one’s racial identity no longer predicted, in a statistical sense, how one fares. When we use the term, we are thinking about racial equity as one part of racial justice, and thus we also include work to address root causes of inequities, not just their manifestation. This includes elimination of policies, practices, attitudes, and cultural messages that reinforce differential outcomes by race or that fail to eliminate them.

‘A mindset and method for solving problems that have endured for generations, seem intractable, harm people and communities of color most acutely, and ultimately affect people of all races. This will require seeing differently, thinking differently, and doing the work differently. Racial equity is about results that make a difference and last.’

Racial equity, of course, isn’t the only kind of nouveau equity afoot. We also have gender equity, transgender equity, LGBT equity, immigrant equity, disabled equity, and perhaps more. What, apart from the letters ‘a’ and ‘l’ sets ‘equity’ apart from ‘equality’? What do President Biden and Vice President Harris think they are going with this renegotiated word? The distinction is not what Harris says (‘Equality means, “Oh, everyone should get the same amount.” The problem with that, not everybody’s starting out from the same place.’) Equality never meant we all should get ‘the same amount’ and if government is now going to assume the role of putting us all in the ‘same place’ by means of a vast system of penalties and awards, we are facing a regime that imagines itself with powers beyond those of Zeus.

But Biden and Harris are clearly up to date. ‘Equality’ does not make an appearance on the ‘Racial Equity Glossary’. The partner terms for equity are, of course, diversity and inclusion, and one would have to write a whole book about those words to make sense of the way language has been stretched to accommodate the identitarian resentments of our age. The demotion of ‘equality’, as in ‘All men are created equal’, is that equality merely promises equality before the law and equal rights, not radical redistribution of resources, and not elimination of ‘attitudes’ and ‘cultural messages’.

‘Equity’ cannot provide those sorts of transformation either. Though we might wish them to be, words aren’t magic. They are more like corks in that wine bottle: useful when they are intact. Not so much when we break them.