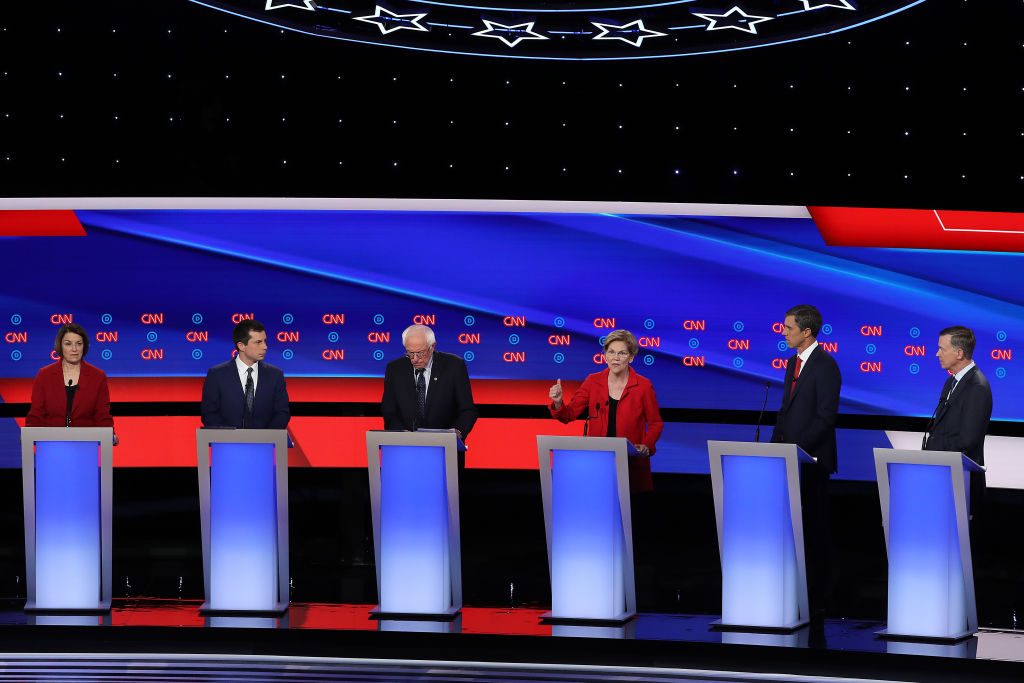

Like some Hobbit or Harry Potter film from 10 years ago, the Democratic debates this summer are so epic in length they must be divided into two parts, each an hours-long endurance test subjecting viewers to candidates 10 at a time, only two or three of whom per night have ever been heard of before. Tuesday’s most familiar faces were Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, the most left-wing of the serious contenders for the nomination. Pete Buttigieg and Beto O’Rourke were the almost-famous figures, the second-tier actors you know you’ve seen before but can’t quite place. And Marianne Williamson, if she was still unknown after the first debate — when she was something of a cult hit — will be properly notable now, having scored in many pundits’ eyes the most points of the evening.

But the night was defined by the contrast between Sanders and Warren on the left and four thoroughly obscure hopefuls from what was once the party’s middle: former Colorado governor John Hickenlooper, Montana governor Steve Bullock, congressman Tim Ryan of Ohio, and former Maryland congressman John Delaney. While senators Sanders and Warren represent solidly blue Vermont and Massachusetts, Hickenlooper, Bullock, and Ryan are the kinds of Democrats one still finds in competitive states in the West and Midwest, while Delaney stands out for the great wealth he acquired as a businessman at the intersection of the finance and pharmaceutical industries. Delaney argued that Sanders and Warren simply do not understand America’s healthcare system, and their proposed fixes for it would be financially and politically disastrous, stripping Americans of their private insurance. Warren chided him accepting that the healthcare game must be played by the rules set by the industry, rather than by visionary politicians like herself or the senator from Vermont. (Bernie, for his part, dismissed Delaney’s business experience by saying that healthcare shouldn’t be a business.) Ryan, Hickenlooper, and Bullock added to the attacks on the paladins of the left, but didn’t make as much of an impression as Delaney, who seemed at times to be playing a role of deliberate spoiler — or perhaps ringer for Joe Biden, if not the RNC.

None of the centrist critics has the slightest chance of winning the nomination, but they underscore a serious problem for ambitious left-wingers like Warren and Sanders. Congress is full of Democrats like Bullock, Hickenlooper, Ryan, and Delaney, and the party’s survival in red, pink, and purple states still depends on such moderates. When Barack Obama won the White House the first time in 2008, he had Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress, and his margin of popular victory was enough that in theory he had a real mandate. Yet the most Obama, with all that political capital, could achieve was the passage of a healthcare reform modeled after the plan enacted by a Republican governor in Massachusetts four years earlier. Should Sanders or Warren win next year’s election, the odds are he or she will still have to contend with a Republican Senate. Yet even if the Democrats were to take the Senate, what kind of Democrats would hold the balance of power? Enough Democrats of the Delaney type to make a ‘political revolution’ of the sort Sanders called for a dead letter from day one.

We know how this story goes because we have seen it played out with President Trump. He won the White House with a Congress entirely controlled by his party, but the Republicans running the House of Representatives were Republicans like then-Speaker Paul Ryan. As a result, no significant, let alone revolutionary, new legislation tackling immigration or trade or any other signature Trump issue was forthcoming. The House and Senate instead poured all of Trump’s political capital into refighting the Obamacare battle of 2010, then finally producing a big tax cut. Trump’s revolution has been stalled by the quality of Republicans he’s had to work with in Congress. Any revolution Sanders or Warren dream of would face the same difficulties from within their party, too.

And yet Warren and Sanders clearly are the future of the Democratic party, just as Trump remains the Republican future. Congress is a lagging indicator, and governors and other state officials in competitive places will find new ways to triangulate between their parties’ leaders and the centrist elements in their states — for as long as centrist elements remain politically salient, which should not be taken for granted as lasting forever. Republicans used to think of the Newt Gingrich revolution that followed the Republican congressional victories in 1994 as a delayed completion of the Reagan revolution of the 1980s. Whatever happens to Trump, Sanders, and Warren next year, their ideologies may also bring about a legislative transformation that lags a few steps behind presidential politics. In short, America’s elections are in for continuing upheaval, and while the likes of Tim Ryan or John Delaney might obstruct a President Sanders or President Warren in the short term, in the not-so-distant future they are facing the same extinction that has come to Paul Ryan. These are wild times.

Appropriately, we therefore have some wild candidates even outside of the left-wing democratic socialist vanguard, and they don’t get much wilder than Marianne Williamson, the spiritual guru who had one of the best nights on Tuesday. She’s simply a more effective public speaker than most of the professional politicians, and she hardly seems any less informed or more unworldly when it comes to policy. She made her stand on reparations for slavery, an easy crowd-pleaser with Democrats. She utterly eclipsed a supposedly serious contender like Sen. Amy Klobuchar from Minnesota, who was on stage but barely registered. Beto O’Rourke and Pete Buttigieg made no gains, either: they remain in the race on the early momentum they built up as flash-in-the-pan young things. O’Rourke has no substance, and his best sales pitch, reminding Democrats that he made Texas semi-competitive in his 2018 race against Sen. Ted Cruz, is in fact a reminder of just how weak he really is: Texas didn’t go blue even with the easily disliked Cruz at the top of the Republican ticket in the best year imaginable for Democratic pickups. If Beto couldn’t work a miracle under those conditions, what chance would he have in 2020, when voters are at their most polarized and out in full force for the presidential election?

Buttigieg, too, appears to have gone as far as he is likely to go: his novelty is wearing thin. He did have one of the best straightforward policy ideas of the night, however, when he proposed that every Authorization for the Use of Military Force should have a sunset provision of no more than three years. That would make endless wars like the one that has been limping along in Afghanistan for nearly 20 years much harder to get away with. Congress would have to renew the grant of force explicitly every three years. And voters could judge them on how they voted.

Foreign policy is the great lost opportunity for Warren and Sanders. Their domestic agenda will run afoul in the foreseeable future of Republicans and Delaney Democrats, even if they somehow manage to beat Donald Trump in 2020. But if one of them could win, a President Warren or President Sanders would have a much freer hand in foreign policy. But to do what? They both emphasized diplomacy over military force, but the question that must be answered is what happens when diplomacy fails. If diplomacy alone cannot check Iranian ambitions in the Middle East or North Korean missile tests, then what? Presumably neither Warren nor Sanders would go to war, but if that’s the case, they should be explicitly making the case that America’s interests do not require Saudi dominance in the Middle East or denuclearization of North Korea. Clear strategic objectives with respect to Russia and China, and elsewhere, ought to be outlined in these debates, too. Diplomacy, like military force, is only a means to an end; and like military force, diplomacy has its limits. There are other tools — economic power being one of them — but what the Democratic debate needed was a more frank discussion of ends, not just means. The clearest answers that any of the Democrats were willing to give on Tuesday had to do with making climate change a key concern of US foreign policy. But most voters still think of foreign policy as being more about war and peace and environmentalism.

Sanders said his diplomacy would rely on the United Nations, which will impress anyone not on the optimistic left as a pitifully weak reed. Warren said she would make it US nuclear doctrine never to launch a first strike. Never — not even if an impending attack by another nuclear power was certain? Should the US forgo even the threat of a first strike, when such threats might resolve extreme difficulties without actual recourse to war? Warren and Sanders both came off as woolly-headed. They are not really running to be foreign-policy presidents, but to shake up America’s domestic institutions, beginning with health insurance and healthcare. Barack Obama and before him Hillary Clinton once dreamed such things themselves, only to find political reality intractable. Warren or Sanders might win the Democratic nomination, but for now the policy realm still belongs to men like John Delaney.