China greeted America’s chaotic retreat from Afghanistan and the Taliban seizure of power with a mixture of glee and trepidation. Its well-oiled propaganda machine has reveled in the fall of Kabul, but Beijing is fretting over the threat of instability on its doorstep — and there is a very real possibility that China will become next power sucked into the ‘graveyard of empires’.

The humbling of the United States in Afghanistan fits nicely into the Chinese narrative of American decline, but Beijing has also used the withdrawal to pile pressure on Taiwan, warning the self-governing democratic island that Washington is an unreliable ally. ‘Afghanistan today, Taiwan tomorrow,’ ran a headline in the Global Times, a communist party tabloid. ‘US will abandon Taiwan in a crisis given its tarnished credibility.’

The newspaper’s editor also shared photographs taken by China’s ambassador in Kabul of China’s tranquil embassy. The carefully crafted images of calm amid the chaos were somewhat undermined though by a hastily arranged joint ‘anti-terrorism exercise’ in neighboring Tajikistan, which shares an 835-mile border with Afghanistan. Chinese and Tajik forces took to the hills outside the capital Dushanbe, while in a letter to his Tajik counterpart China’s minster of public security said, ‘The current international situation is changing and the regional counterterrorism situation is not optimistic.’

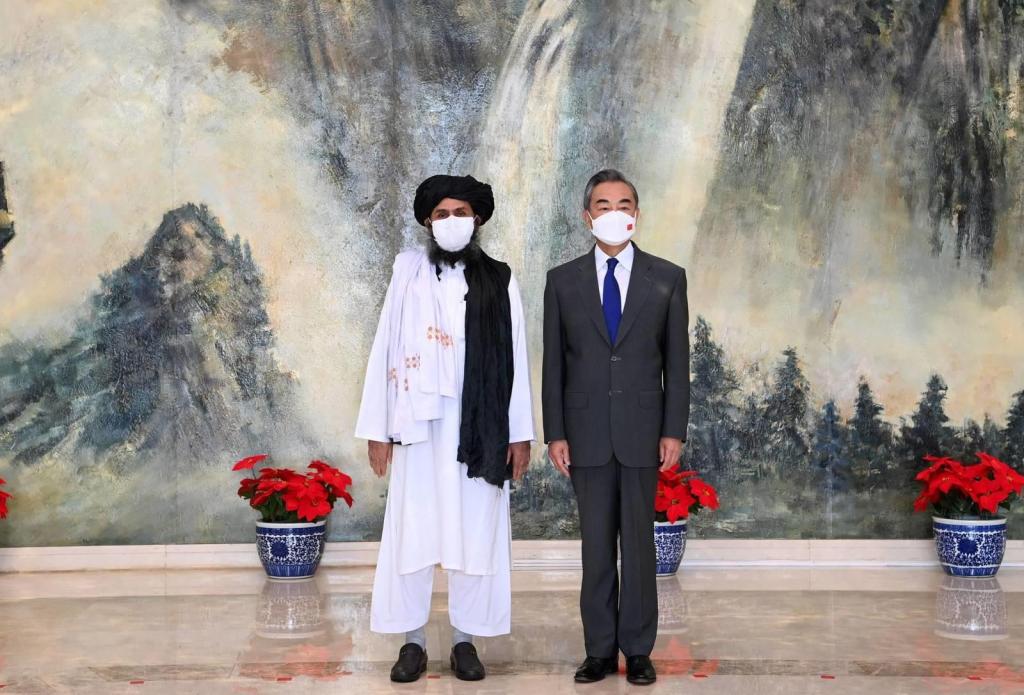

China has declared that it will respect the ‘choices’ of the Afghan people, and is moving quickly to build ties with the Taliban. It hosted Taliban leaders in Beijing even before the US withdrawal was complete. That followed a growing number of contacts over recent months as the endgame in Afghanistan became increasingly clear. Beijing is holding out the promise of investment as part of its Belt and Road Initative (BRI) of international construction to rebuild Afghanistan. A priority is likely to be the development of the world’s second largest copper mine, 19 miles southeast of Kabul. China has a contract for the mine, but the project stalled as a result of security concerns.

Afghanistan sits on mineral deposits worth an estimated $1 trillion, including the world’s biggest deposit of lithium, an essential component of the rechargeable batteries that will supposedly power our green future — quite a prize, if the country can ever be stabilized.

Neighboring Pakistan is the biggest recipient of China’s BRI funds — it has received an estimated $60 billion splashed on roads, railways, ports and other infrastructure. Chinese diplomats talk of Afghanistan becoming an extension of this, with Pakistan also acting as a political conduit to the Taliban. Islamabad was the group’s main backer when they were last in power, from 1996 to 2001, and harbored its leaders when out of power. But Islamabad’s influence over the Taliban is often exaggerated, and Pakistan itself has been plagued by religious extremism and occasional violence. Last month, nine Chinese engineers working on a dam project were killed in a bus explosion in the Kohistan district of Pakistan.

Beijing’s fears instability on its doorstep more than anything else. Ironically, it has been one of the biggest beneficiaries of the stabilizing presence of the US and its allies. Chaos in Afghanistan will threaten its projects in Pakistan and other central Asian states. It also fears a spill-over of radicalism into Xinjiang province, which shares a narrow border with Afghanistan, and where the repression of the Uighur people and other Muslim minorities has been labeled as genocide by the United States and many other western politicians. Beijing has reportedly sought assurances from the Taliban that they will cut ties with the East Turkistan Liberation Movement (ETLM), which Beijing blames for attacks in Xinjiang (which the Uighurs call East Turkistan).

While Uighur militants have appeared in Afghanistan, most independent observers believe their number and influence is exaggerated by Beijing, which uses a very wide definition of terrorism to justify its clampdown. That said, it is not unreasonable to assume the Taliban takeover will inspire opposition — even armed resistance — to oppressive Chinese rule in Xinjiang. After all, the Taliban are a bunch of militant Islamists, and Beijing’s actions across their shared border constitute an attempt to eradicate the culture and religion of an entire Muslim ethnic group and turn them into obedient Chinese citizens — the most comprehensive assault on Islam in the world today. Piles of BRI dollars have blinded Pakistan’s prime minister Imran Khan to that reality, but even the most pragmatic of Taliban might not so easily be bought off.

China will approach Taliban-ruled Afghanistan with the same hard-nosed assessment of its interests that drives its global expansion elsewhere. It has no issue with cozying up to odious regimes, as the recent invitation to Syria to join the BRI testifies. But it does raise the question of whether chaos in Afghanistan could lead to the involvement of Chinese security forces there and in the region more broadly. In some ways this is already happening — the Tajikistan exercises are the latest example of this. Beijing already deploys what have been described as private security contractors to protect projects in Pakistan, although these groups are far more closely linked to the state than is the case with western contractors.

President Biden justified the withdrawal from Afghanistan as being in part a way of freeing America up to concentrate on meeting the challenge from Beijing. If China becomes the latest empire with imperial ambitions to be sucked into the quagmire America has left behind, that might suit Washington just fine. That might even have been part of the plan.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.